Work Life Balance

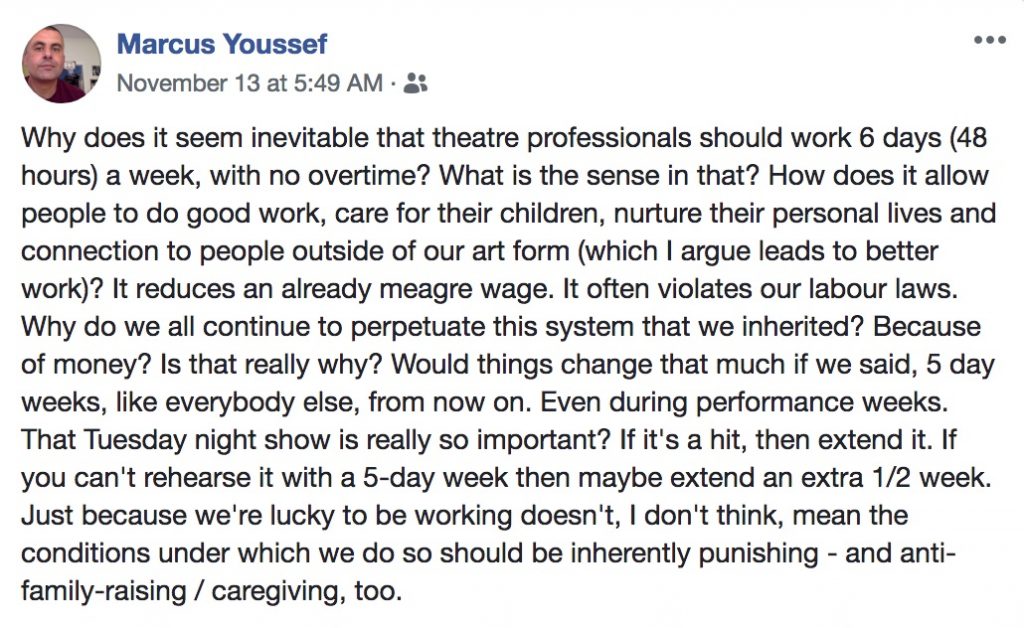

Much is being discussed about life work balance. I would not be so foolish as to take an opposing view on the necessity of our industry (not just the theatre—but the entire performing arts community) finding pathways to a better point of balance. I will however write about the direction of some of the discussions happening. The discussion seems to be focusing on five-day weeks and shorter days as a panacea for providing life work balance.

Presuming that we are not seeking less rehearsal / development / exploration time for the art, we would then be talking about extended engagement periods. Not a bad way to go—(finances aside)—if you are in a major centre where your creative team live.

For rural, remote communities, and for smaller cities, extended rehearsal time may in fact add strains to life—especially family life. My company currently engages actors for eight week contracts to complete roughly 120 hours of rehearsal, another approximately 20 hours of tech rehearsals and 31 performances.

We are on an island, and while we are a small city with a decent number of talented professionals locally, we also rely pretty extensively on a national talent pool. Out-of-town artists are required to be away from their principal residence for an extended period of time. Presuming again that we want to maintain an average of 40 hours or so a week in rehearsal time, would we (and others like us) then ask actors to be away from home for even longer stretches of time?

Moving away from rehearsals and overall contract length, I would like to also offer that a presumption that we could accomplish the same impact with audiences in a five day week rather than a six day week, also offers some challenges. While it is possible that my company could reach the same number of audience members most of the time with fewer performances; the data we have does show that for many of our shows we would not.

In the age of ticket sales needing to draw a majority (or at least significant portion) of our revenues, how do we find ways of paying are artists better? Which I believe plays a really significant part in providing life-work balance. Which day do we give up to ensure we reach the community we serve? In our case that would likely be Friday and Monday. -not an ideal way of moving to a five day week.

As artists, as companies, we share a responsibility to our audiences. They too need to be part of the conversation and solution. We rely on them for our livelihood. Perhaps we can reverse the stream of 24/7–365 consumerism. I suppose if anything should attempt it maybe it’s art. However, whether we like it or not, we are part of the consumer society and if we are to affect change we need to find a way to bring our audiences with us.

This is a short, starter conversation. It is a conversation that is particularly important and valuable. In each work day, we should be finding ways to provide the responsiveness to meet the needs of all of us, to have and respond to our life as well as our art. We should be particularly cognisant of the needs of mothers and other primary care givers. I wish I had an answer for improving balance in the lives of our artists and craftspeople. I don’t. But I do know that a single version approach can create as many issues as it solves.

Our current model of how we create the work, how we perform, how we become truly inclusive, and how we continue to move away from the culture of poverty requires dedicated and intensive conversation. That conversation can not start from a perspective of us versus them. It is not an artist against organization issue.

It is also not starting from the intractable position that organizations (and individuals) fall back on—‘we’ve always done it this way’. I believe that it also can not start from a one size fits all response. That the needs of our audiences, our community, our artists, our staff, must all be part of the discussion and solution. That voice must be given to each individual involved, in each process, in each circumstance.