This is the fifth in a series of articles capturing the planned conversations and discussions at the inaugural Festival of Live Digital Art (foldA), in Kingston ON, June 19-June 21, 2018. Chris Tolley writes about a conversation between Milton Lim, Beth Kates, and Rose Plotek that was presented in the Green Room of the Isabel Bader Centre for the Performance Arts titled “Digital Dramaturgy”.

I suffer from Obsessive Compulsive Digitalorder.

Most nights I strap my Thync, a neurostimulator to my head in a quest for mind and memory enhancement. When I slouch, my UpRight sensor sends a jolt to my lower spine prompting me to stand tall. Each morning my Omron scans and tracks seven body metrics, from my resting metabolic rate to my visceral fat count. I even have a backyard weather station that updates to the Cloud. And we all know that’s bullshit.

Yes, I am a beta-slut.

Yet, if I was to be completely honest and ask myself, do any of these cutting-edge / experimental / wallet emptying digital innovations truly make me a better person in any measurable way whatsoever – well – I don’t think I’d like the answer.

And I know, this soul-crushing question doesn’t stop there. There are many ways this part of my life, and accompanying existential anxiety, overlap with my artistic practice.

Having incorporated, or in some cases admittedly squeezed, digital elements into every theatre production I’ve created since 1998, I often find myself wondering, is this really serving the narrative?

Writing in 2006 for the London Observer, John Heilpern laid out his pecking order of culture: “I don’t go to Oprah Winfrey for the truth. I go to the theater instead. That fragile, fantastic thing we call the theater has always seemed to me to be the last place on earth where our stories can be truthfully told.”

Heilpern’s understanding of the relationship between art and truth is worth noting as he is the author of the seminal book, Conference of the Birds – The Story of Peter Brook in Africa. In this book, he recounts the epic journey Peter Brook took across the Sahara desert in search of a new form of theatre, one that explores honesty in art.

So, if we agree that honesty, or more accurately, authenticity, is the ultimate quest in our artistic practice, what we need to ask is, does technology bring our work any closer to the truth in ways text or movement can’t, or is it nothing more than a DIY weather station spinning in the wind?

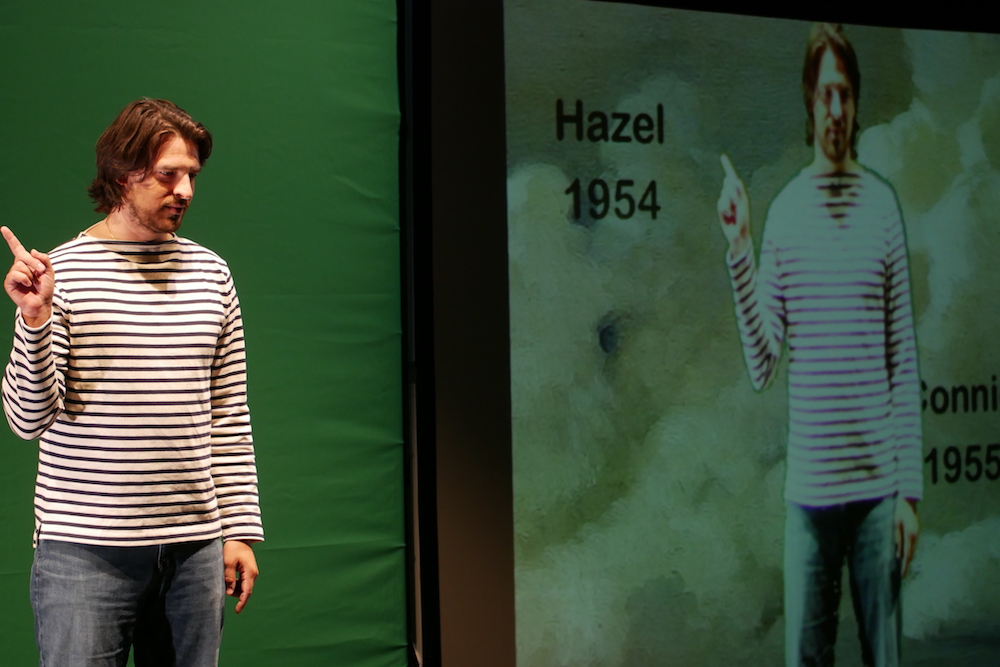

I was thinking about this as I entered the Green Room at the Isabel Bader Centre for the Performing Arts in Kingston for the inaugural FoldA Festival’s Digital Dramaturgy seminar. This impressive room, boasting 20-foot tall floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking Lake Ontario, was home to the hour-long debate about technology and how it can best serve theatre.

There at the front of the room was Milton Lim, one of our country’s most intriguing directors/designers. While most of us are exploring what we think are innovative practices like projection on live actors, this digital maverick is experimenting with doing away with actors altogether.

His piece okay.odd is a technological mashup; an experiment in gaming mechanism, textual frequency and automation. By completely replacing actors altogether, Milton pushes the boundaries of what we can even consider live performance. Is okay.odd a video installation, performance art, or the next wave of digital theatre? Can it even be considered theatre if there are no live actors gracing the stage?

And really, do any of these categories even matter anymore?

I met up with Milton later in the day. He was preparing to meet a Queen’s professor who had developed a holographic protocol for transmitting images digitally, basically a 3D Skype. Milton was going to connect with the professor to see what potential applications there could be for the performing arts.

I was both spellbound and, I have to admit, a little wary by this thought. Clearly, we are moving rapidly towards a world where the word ‘live’ in ‘live performing arts’ is by definition changing. Augmented reality, virtual performers and reactive sets are all moving us closer to a digitized, otherworldly experience. Otherworldly, yes. But authentic?

A vigorous debate about this very question broke out at the digital dramaturgical seminar. The conversation took on a heightened level when panellist, Rose Plotek, Associate Director of the directing program at the National Theatre School mentioned that all directing students were required to work projection into their final productions.

The merits of this are obvious; if an artist is to experiment with, and possibly fail in such a complex medium, an educational environment is the safest place to do so.

Yet, an obvious counter to this argument and one raised by several at the seminar is whether forcing projection into every new work contributes to the gratuitous use of video, something we are seeing increasingly in the arts today. Does, say, a flowing river spanning the length of a scrim truly support the narrative, or is it nothing more than a cheap device littering the stage?

Of course, one can turn this argument in on itself, and this is probably the thinking behind NTS’s program. Perhaps muscling video into every production forces students to think about, and discover, the delicate balance facing all digital designers; the balance between technology truly serving theatre, and the inverse – where the production is nothing more than a slave to the technology.

As discussed in other panels over the three days at FoldA, the impact digital distribution has had on bringing our sector together is undeniable. When working in a country as geographically vast as Canada the ability to share work, via green screen enhanced two-way transmission, podcasting, and other technological innovations, can only bring our work closer to each other. But as the lively debate at the dramaturgical seminar demonstrated, the benefits of the artistic applications of digital are far more complex, and potentially perilous. The possibilities of failure are acute.

I left the workshop mulling over the delicate balance between Heilpern’s quest for truth and authenticity in art, and digital innovation. Do these technologies help us make better art, or are we merely getting caught up in a collective obsessive-compulsive digitalorder – an uncontrollable impulse to play with the latest and greatest beta release?

As the panel made clear, we are working in uncharted, artistic territory, and no one knows where this fine line truly lies. Yes, there is always risk when working on the cusp of innovation. However, the risk of inaction may be even greater.

And, ultimately, is the value really in the answer to this question, or much like the art we aspire to, is the true value in the very act of asking the question in the first place?