Taking Care: Down to the Very Last Pixel

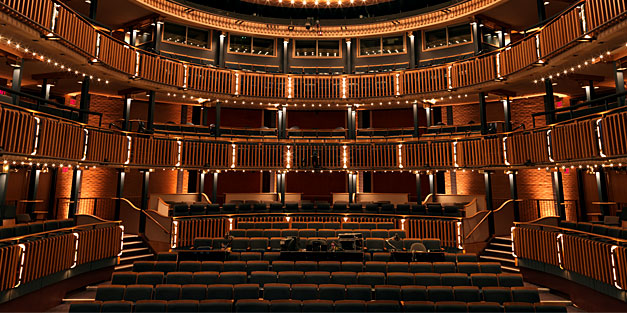

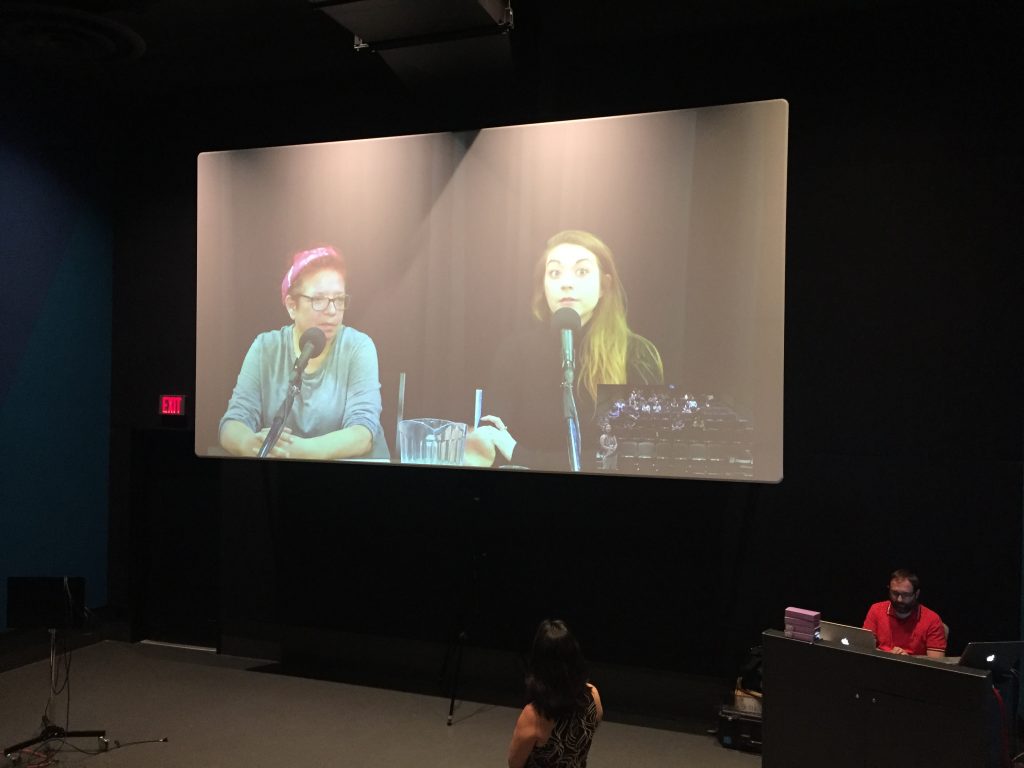

This is the eighth in a series of articles capturing the planned conversations and discussions at the inaugural Festival of Live Digital Art (foldA), in Kingston ON, June 19-June 21, 2018. Rose Plotek writes about a moderated conversation between Mikaela Davies, Elissa Horscroft, and Keira Loughran that was presented in the Screening Room of the Isabel Bader Centre for the Performance Arts titled “Live from Stratford”.

I was asked to write about A Conversation Live From Stratford: Behind the scenes of Robert Lepage’s Coriolanus. This was a conversation between Elissa Horscroft (technical director), Mikaela Davies (assistant director), and Keira Loughran (associate producer for The Forum and Laboratory at the Stratford Festival), and was live streamed direct from the Stratford Festival to the Isabel Bader Centre for Performing arts, home of foldA.

The focus of the conversation was on the digital technologies used in the production. The digital tools used in the show are innovative in the interaction and integration of automation, video and lighting together. Though this kind of work is being done on other productions at the Stratford Festival, (this season primarily in The Rocky Horror Show), the extent of its use on this production is much more detailed, and there is simply a lot more of it. In order for the production to be fully realized the integration of these elements had to be fine-tuned until the relationship was seamless. Down to the very last pixel.

In this conversation Elissa Horscroft, technical director for the show, noted that Lepage has been clear about the fact that none of the digital technologies used in the show are new; it’s the way they are being used that is innovative. Horscroft notes that we are seeing these tools used more impactfully as we get better at using them, and as the technologies themselves continue to be developed.

The system used in this production is called VYV and was purchased by the Stratford Festival for this production through grant support. It’s a system that facilitates the integration of all the technical elements of the show (projection, automation, light).

Hoscroft notes that it’s been a very steep learning curve for the Festival’s production and creative team working with this system. VYV is entirely open, which means a lot can be done with it, but you need to know how. For the festival team the subtleties of the system were difficult to master.

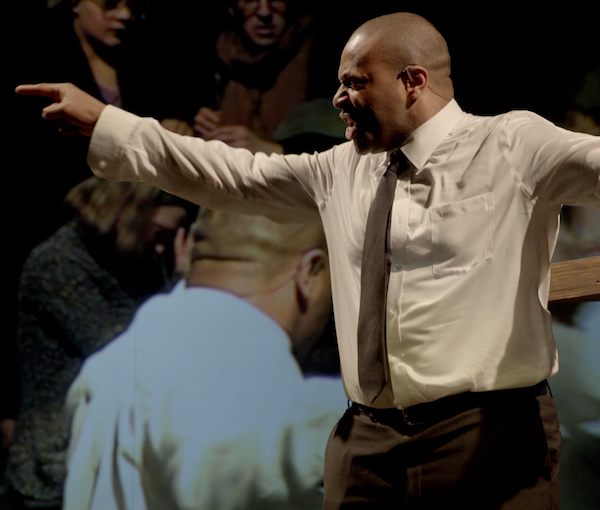

Mikaela Davies, assistant director on the production, spoke about how the production flirts with antiquity while being firmly set in 2018. She described the digital tools as contributing to the dramaturgy of the piece. The use of technology allows the production to change location in an instant. The intention is to activate public and private space, facilitated through projection, to elevate the story, taking what is already in Shakespeare’s text but adding more dramatic tension. In this way, the technology aims to make the production culturally relevant to us in 2018. The contemporary locations, accomplished through projection, make it resonant for our world, which for Lepage is important when dealing with the classical canon.

Davies notes that Coriolanus uses cinematic tools to tell the story: the projection screens are used to create fades, cuts, etc., all tools that come from the cinema and keep the action moving at a rapid pace.

My main thought while listening to this conversation was about the people involved. How is the festival taking care of its production and creative teams, who have to learn and integrate these new tools without burning out, since the learning needs to happen as part of the production process?

Though the festival did workshop the piece over a number of years to accommodate for this shift in production model, is the institution making sure that they are taking care of their people? What can the institution do to train and educate a larger group of people so they can support each other when more and more productions are going to be integrating these new tools?

I also can’t help thinking about Lepage, his productions of SLĀV and Kanata, and about the cultural appropriation and insensitivity that his work and he himself frequently exemplify. He is relentlessly unable to admit the slightest flaw in his own conduct or sensibility. Instead he releases fatuous statements posing as historical accuracy and timeless truths, arguments used by authoritarians since the dawn of time.

In these cases, Lepage seems to demonstrate no care for the communities he is representing on stage. He is deaf to criticism. The startling announcement that the production of Kanata will go ahead makes me wonder how much care is being given to the experience of the artists working on the production in view of the storm of controversy in which they will be immersed.

Since when has artistic freedom come before human empathy?

It seems that this form of auteur theatre making, that works so hard to make works “relevant”, is perhaps now itself becoming problematic. In a climate where collaboration and humane work conditions are increasingly valued, can the authorial vision of Robert Lepage, his way of working, fit within a new ethic around work?