Thought Residency: Michael Wheeler

I’ve been reading a lot about how automation is going to change the nature of work – that it won’t just be factories, but it will be lawyers and accountants, and even doctors. So much of what humans do as work currently will be automated through robots and algorithms. And then the question is what do we do with our time? Now that our bodies are not required to generate capital. And, uh , i don’t know: Make plays, start the revolution?

Is there anything more anachronistic than the Royal family? Who cares about this wedding? Why do we care? Why do we allow this family to be on our money, to avoid paying taxes, to have to sign our laws? What have they done? They’ve accumulated wealth. They do not adhere to any democratic principles and yet we place them at the top of our society.

Let’s evolve as a people. Let’s take agency into our own hands. Let’s abolish the monarchy and have a Republic in our lifetime. It’s time.

If the reason a society should support artwork is that it is an economic driver that contributes to a creative economy, if we were to determine that art did not drive the economy, should we then not have art?

Hear that sound? Hear that sound? That’s the Fisher Price, I don’t know, “bounce and play” I’m gonna call it. Anyhow, this thought is about being a parent and how before I was one I was sure that it would be hard because how would I get any work done with all the diapers and the no sleeping and carrying and bouncing and uhh it is really hard to get work done but not for those reasons. Mostly because Noa, my daughter, is so darn cute that I can’t imagine why I would do any work when she’s around. So that’s why I have to leave the house actually.

One of the things that’s different about being Canadian than American is we celebrate Canadian Thanksgiving. Much earlier. Mid-October. This means there’s no breaks between Mid-October and Christmas. We go straight. No holidays. No nothin. Just workin. Hard. Dark. Days. Gettin it. Done.

I first joined Twitter in December of 2011. Since they I have made, apparently 19.2 thousand tweets. And all those little messages that I have sent out into the universe have reshaped how I use language. In particular, how I can be brief in making my point. Now that Twitter has doubled the character limit to 280, I imagine this will shape again the way that I use language to express myself, aaand I hope I don’t become more long-winded.

A recurring concept in the arts is: Entrepreneurship. How can artists be Entrepreneurs? And one one hand i think that’s a really amazing idea, and in particular that artists can control their own destiny by being entrepreneurs that make their own work. And on the other hand, the idea that art should be profit-driven is antithetical to what makes it valuable.

Many aspects of a personality combine to create a single self. I’ve been contemplatiing this in relation to basketball-playing Mike, who is loud, often aggressive and mm, rehearsal director Mike who is a listener, collaborative and not ever yelling at anyone that I can recall. Ah and they both feel like me, and I like both those people, but which one is the real me? I think the both are.

This is Michael Wheeler and this is Thought #3.

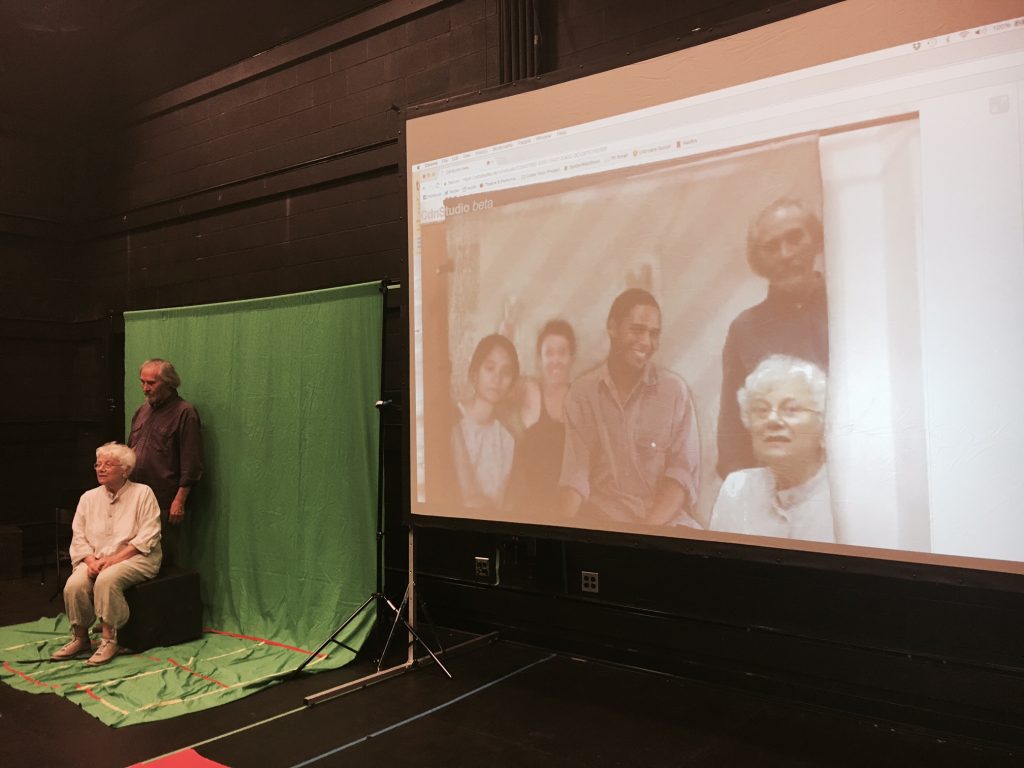

My students at Queen’s University are beginning a process of creating scenes through CdnStudio. They have the benefit of actually rehearsing those scenes in person with each other first, before they start creating across distance.

I’m curious to see how this changes the creative process in comparison to something like our production of The Revolutions which used the technology to create a work where artists from a cross the country collaborated with each other without ever being in the same space.

Seems like being able to meet each other in the same space will change things.

This Michael Wheeler and this is Thought #2.

I’ve been thinking today about Progress Lab in Vancouver and how it is home to both Marcus Youssef, who is the most recent winner of the Siminovitch Prize and also The Electric Company and Kim Collier, also a winner of The Siminovitch Prize.

And how that space was created by a bunch of artists who came together and figured out how to pool their resources to give them the infrastructure they needed to explore their craft, before anyone had won any Siminovitch Prizes. And ah, it just reminds me that working together you can achieve a lot of things.

This is Michael Wheeler and this is Thought #1.

I’ve been thinking a lot about branded content lately, and how newspapers and magazines now offer theatres the opportunity to purchase the coverage they used to receive for free from journalists and their publications.

And that the model, the business model that supports the media, is suffering is so much that now you buy what used to be, omm, news.

And that that is bad for art, because then news, in the art world, is about the people, who can pay for it.