What’s Fair?

In the arts, we love fairness.

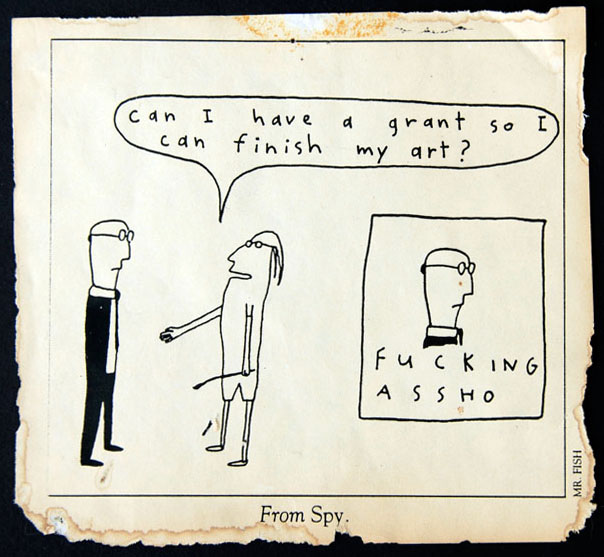

We talk endlessly about what it is, and are outraged when we feel it isn’t enacted as we believe it should be. We have developed complex systems of committees, juries, and boards to ensure that fairness reigns. We recruit experts (artistic and administrative) to evaluate. We use systems based in math, weighted results, and spreadsheets and we engage impartial facilitators to oversee processes. These systems are designed with the idea that if the gate is unbiased and those who want to get through it work hard enough, our resources will be shared appropriately. These days in the arts, fairness is about what is on paper and due diligence to our systems – it is a performance of fairness.

Ever increasingly I find work in service of the arts in contention with this idea of fairness. I have spent the past handful of years listening to understand the needs of Indigenous, POC, and women-identified artists and arts leaders. I have seen and heard that where the current system fails these artists is in their sense of belonging. If we as a sector are dedicated to fairness, we must stop performing fairness and work in a model where fairness is felt. It is incredibly challenging to belong to a system that you don’t feel is fair, isn’t designed for you, and has inherent contradictions. For fairness to be felt, we need to look at leadership models that create a sense of belonging and humanize each other, creating reciprocal relationships of accountability.

“True service is not a relationship between an expert and a problem; it is far more genuine than that. It is a relationship between people who bring the full resources of their combined humanity to the table and share them generously. Service goes beyond expertise. Service is another way of life”

– Rachel Naomi Remen, MD.

Capitalism

Capitalism teaches us if we work hard enough, we will succeed. Our successes are the result of this hard work and our success will trickle down for the benefit of others. Capitalism is founded on the belief that it is fair and that everyone has an equal chance at success if they work for it. In capitalism, success looks like growth, an increase in wealth and accolades. Fairness is about how you distribute the products of that success. This focus on growth works against belonging and community accountability as it encourages competition. Capitalism doesn’t want us to be transparent with each other about how we got what we got and what we do with it.

Charity

Organizational charity was designed by capitalists to offset their personal profits and to find ways to incentivizing charitable giving by reducing taxation. They had a philanthropic agenda and altruistic concern for the well-being of society, assuming a role as patrons. A patron is someone who supports with resources, takes one under their favour or protection, and lends their influential support to advance the interests of someone.

In charitable organizations, we largely evaluate based on statistics: number of audience, money spent directly on the art, low administrative expenses, low cost to raise a dollar, etc. We evaluate leadership based on these numbers and invest in order to increase these gains. Leadership based on belonging is harder to measure: it takes years to evaluate its effect and is time consuming. We don’t like to take risks with philanthropic dollars.

I am suggesting that change occurs more readily when working the system and subverting it from within. To do that work, arts leaders need more agency in the processes they create a shared sense of belonging within the system. This sense of belonging must be predicated on belonging to each other and not an evaluative patron. Our current requirement to perform paper-based fairness holds this back and sets an expectation that belonging comes from the systems that determine if we get the resources or not.

When I started out as an arts administrator, I was taught that organizations are like boxes and as their staff it was our job to caretake these boxes, under the supervision and guidance of the volunteer board of directors investedin our philanthropic agenda. I treated the many organizations was involved in in that way – we discussed changing the colour of the boxes or how to repair corners that had been broken and put various policies or procedures into place that ensure that the next caretakers of these boxes would understand how they were built and had been adjusted or cared for over the years.

These days, I prefer to see the organization like a coat. A coat without a body is a pile of fabric on the floor. A coat needs a form to inhabit it and just like in fashion, we do not all wear coats the same way, nor do we care for our coats in the same way. Seeing organizations as coats allows us to celebrate the person in the coat and the finesse with which they wear it. Our systems teach us to not celebrate the individual. The box metaphor is undermining those who have dedicated their lives to leadership in the arts by externalizing their work.

Seeing organizations as boxes that we care for puts the leadership of that box in the background, as a caretaker. This role of temporary caretaker is detrimental and I see it as a major reason that many of my peers have left the arts or taken positions in larger institutions. Leaders can go for years feeling invisible =in a culture that cares for the organization and not the person(s) behind it. If we instead shifted our cultural focus to the individual leaders who are making change supported by a community, these individuals would be bolstered and their ideas and actions would be reinforced, leading to longer careers with bigger changes in the communities they work within.

I have seen in my own work how powerful it can be to invest in an artist over an extended period of time. My work has focused on individualized, focused career coaching with folks who are tenacious, driven, lost, and often at wits end. My work as a coach with Scaffold in Vancouver is a way to work with artists by providing producing support, networking, information and resource sharing, life coaching, external accountability, creative community and bridging to institutions. At Generator in Toronto, we invest deeply in a few artists and devoting hours of time, training and coaching.

The cost of this investment is significant, but the benefits are vast. With both programs, the individuals have stronger skills, a clearer sense of what they don’t know, and the confidence to push their careers forward. We are creating communities of competent and confident artists who understand the risks and challenges of a career in the arts and how to offset them.

This kind of work is a shift toward a model that has high expenses and low statistics. It doesn’t perform fairness as it is traditionally measured. This kind of work is about being in service to a community and being held accountable by that community. It serves a few, serves them well, selects them specifically – creating a sense of belonging by investing deeply and opening pathways to systems that have excluded historically. The model serves the individual, not the organization. In ten years, the artists that Scaffold and Generator have invested in will be leaders. They will know the systems, understand how to use them, have communities based in belonging and accountability. They will make changes we can’t imagine.

Change will come with the freedom to support and generate the communities that will alter the sector. These communities will feel like the system is fair and will hold their leaders to account when these investments aren’t working. This work is dismantling the structures we inherited.

The arts game is rigged for the settler. As a settler, I know this game. I’ve played it well. I can take what I know and help guide Indigenous, POC and women-identified artists through the system, point out the small cracks in the walls, act as a guide by translating documents and application forms and identifying beaurcracts sensitve to their cause. To support independent artists in finding ways to make art outside the currently prescribed modes you have to know the rules to break them and you need to belong to something to have the resilience to survive.

Ideas for this article came from a variety of sources besides my experience, I want to acknowledge some of the individuals who helped me form these ideas: Cole Alvis, Claire Love Wilson, Joel Klein, Rachel Penny, Nikki Shaffeeullah, Ruthie Luff, Chiamaka G. Ugwu, Andrea Scott, Michael Wheeler, and the others whose ideas wove so deeply into mine I have forgotten where they started. Rachel Naomi’s quote is from the essay “Belonging” in the book “My Grandfather’s Blessings” by Rachel Naomi Remen, MD.

A couple weeks ago I downloaded an app that tracks how much time I spend on my phone. Among the many ways in which I fear I am constantly failing myself and everyone around me, I worry about that a lot. I worry that I’m not present enough. I am ashamed of ever appearing like I’d rather be somewhere else.

A couple weeks ago I downloaded an app that tracks how much time I spend on my phone. Among the many ways in which I fear I am constantly failing myself and everyone around me, I worry about that a lot. I worry that I’m not present enough. I am ashamed of ever appearing like I’d rather be somewhere else.