Dear Letter Writers,

Piss off, and fade away.

An open letter is a very valuable thing. But when it’s overused it just comes to mean nothing. When a media service publishes an open letter, it is for the purpose of dissemination to a wide community. The idea being, concerned citizens are given the chance to publicly address the targeted recipient in the purview of a larger public. This may then force a response from that recipient. For example:

An Open Letter to Coca Cola,

You’re evil. Stop privatizing water.

Sincerely,

A Concerned Citizen

A Response:

No.

Happy Holidays,

Coca-Cola

P.S. Ho Ho Ho ©

So, an open letter can be used to make a statement. The powerful body’s response (or lack there of) will, at the very least, colour the overall picture of that recipient in the views of the larger community of readership.

So, why are open letters becoming so prevalent?

I wonder about this. Maybe we’re all just angrier. There is a lot to be angry about… but what if there’s not actually more to be angry about? So here’s a stab at what I think is going on:

There’s a science to “why we post.” Supposedly, it’s a dopamine rush. Any old post, when it’s “liked” or “favourited” – it gives a sense of validation. And actually causes a small neuro-synaptic rush. It’s the same kind of thing that happens when you express your outrage of something in your life to a friend, and they say: “You are so right.” So that’s all well and good, right?

Well, not really. As it turns out, the more we do this – the more validated we are constantly – the more we crave and demand it. A lack of validation, or worse yet a criticism, starts to cause us irritation. Gradually, it makes us less tolerant of opposing views, and it even can transfer to an increase in “real life” micro-aggression, or anxiety. It’s like an addiction. And that also means part of the picture is dependence and withdrawal.

Dead Letters and Live Artists

While there are certainly exceptions to the rule, in general, I feel that open letters by (and perhaps more apt would be between) theatre artists seem counter to the art from. What is theatre, if it’s not a forum for the exchange of ideas? A performance is live – and that’s what makes it dynamic. Likewise, conversation is live.

To delve into a little bit of Kantian Aesthetic thinking – if we consider the binary of concept vs image – theatre is image. It is the liveness itself that keeps it as such – an ever moving and malleable thing between the performer and the audience. It’s affective less than intellectually finite. Open to interpretation.

The opposite of image is “concept” – which is a known. A dead letter. The imag(e)inative potential of a concept is basically nullified by the existence of the concept itself. Concepts are useful in terms of stepping stones to a larger imaginative idea. They are the roots we can grab hold of while we topple blindly down the cliff face of imagination.

Theatre, live performance, whatever it is we do… is like a village square. To extend the metaphor – an open letter is a fortress. A fortress constructed and crafted from an often well researched argument. It conceptualizes its statement and works to create barriers – or castle walls – to any disagreement. It’s almost totalitarian in that way, whereas the city square is relatively democratic. I don’t want to come to your castle to be lectured at – it’s pointy and cold. I’d rather live in the village square. And the reason? Because there, we talk.

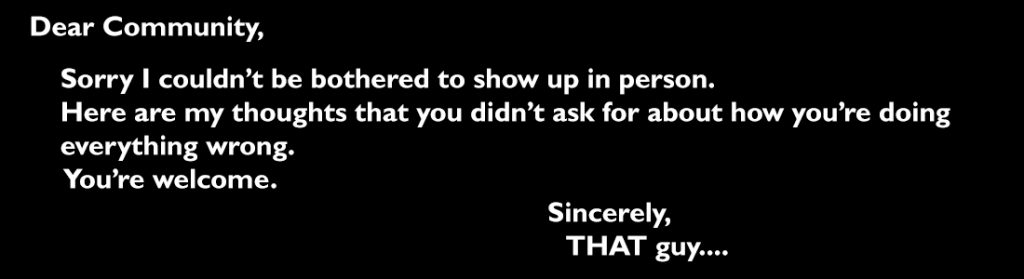

An open letter side steps conversation. It allows its audience to take a somewhat removed objective stance and say whether they agree or disagree with the concepts put forth. Meanwhile, that same audience can distance itself even further by responding in similar letters – rather than doing something crazy like talking to someone about it. Maybe even talking to the writer. And why would you want to talk to the writer anyhow? They’ve said their piece, and often when someone disagrees or “denies” them that requested dopamine satisfaction – they get angry.

As live artists, we have the capacity to make statements in real life. We have platforms. We’re generally pretty ahead of the game in terms of rhetoric. When we sit in our fortress of solitude and make statements – we are prescribing a wavelength and trying to force others to accept it rather than jamming on an idea. It’s not necessarily malicious. But I do think it’s lonely. And that makes me concerned.

Look, if you wanna say something controversial, progressive, accusatory or perhaps even offensive – go right ahead. But please face me when you say it, and know that you very well may be challenged. And you’ll be challenged in front of everyone. And there, in front of a community you would otherwise write to from a safe distance, you can confront your opinion and try to justify it, or you can learn to listen.

Understand, it’s ok to be wrong. All you need to do is listen, hear, consider, and say “Oh, right. Yeah, I was wrong.” Or say “I’ve listened, and I still don’t agree.” But say it. Don’t be an isolated indisputable concept. Be an image. Let me see the image of someone who is hurtful and uninformed negotiate how they must now share space with the people they just pissed off. That’s interesting. And maybe, just maybe by hearing the genuine inflexion in someone’s voice, or seeing the immediate facial reaction, or feeling the way the tone shifts in the room will at least give perspective as to why they don’t like what you’re saying. Or why you’ve just said something they needed to hear.

The more we rely on these open letters, the more we choose to broadcast rather than engage, the more we distance ourselves from the actual importance of the art form we work with – we are abandoning the medium of liveness. So let’s do something radical. Let’s try being in the same room. Let’s try talking to each other. And let’s make mistakes.