I am a gay Christian. You may have heard of us; we’re mythological creatures that live outside the comfort of the church because of our queerness, while also living outside the comfort of the LGBT community because of our bent towards a faith that has so wounded non-heteronormative people. I am also a theatre artist.

Daily, I feel the turmoil of how deep the rift is between the multiple communities I belong to. The institutional church has a bad rap and the queer community is wary of engaging with Christians in response to the harm the church has inflicted. Add to that the tendency of theatre to challenge, criticize, and dismiss organized religion as a crutch, as unscientific and grasping for control (bastion of patriarchy). How does it look to you? I am on the front lines of a culture war.

I have always hated the idea that identifying either as gay or as Christian assumed a polar opposite cultural position. Coming out was hard enough in the church, but coming out as a Christian in the queer and theatre communities is also extremely challenging. The good part about holding an identity that screams dissonance is that I get to be in on the conversation, and when I have the energy, I can add my voice to it. I add the part about energy because trying to hold a gay Christian identity also makes you vulnerable to being written off. Sometimes it feels like I don’t belong in both worlds; sometimes I feel like I can’t exist in either. I decided I needed to write myself into the present and imagine in that writing how I would give myself a future.

Writing my first play, which I called oblivion, was about getting people into my mind to witness how damaging it is to try to sterilize sexuality because of religious faith. I had spent until age twenty-six trying to be good enough for the church and God, to heal my sexual orientation through reparative therapy and other damaging beliefs. Ultimately, that failed and I left the church in 2011 to come out. The reaction from my Christian community was so damning that I not only walked away from my church, I also gave up on my faith. By the time I was ready to get my story down on paper, I was no longer calling myself a Christian.

To write oblivion I ventured to tell a slightly fictionalized story of a gay man in a loving relationship haunted by his conservative Christian past and looking for a way to be cured of his faith so he could be at peace in his life. It was based on my truth: that the church had failed to cure me of my homosexuality, but by their so-called “love” response to me coming out they had cured me of my religion. oblivion is my contribution to this ever-polarizing conversation about faith and sexuality. It theatrically illuminates the very real internal struggle between sexual identity and religious conviction and reveals the harm and mental illness experienced by someone caught in the middle.

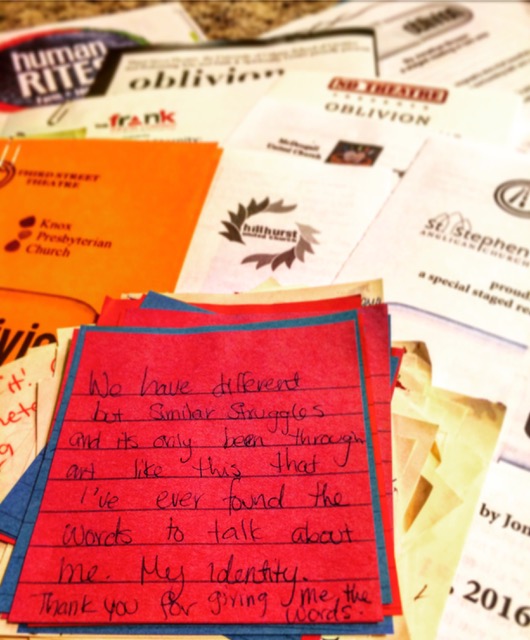

What resulted initially was a fifty-minute workshop production during the University of Calgary’s 2013-2014 student run ND Theatre season. Audiences were compelled by the show, and the post it note board was overflowing with questions and a desire for more dialogue. When I was invited to develop the show further at Vancouver’s the frank theatre in 2015 for their Aspect of Eternity series, there was a short time allotted for feedback about the show with myself and the actors. This conversation was supposed to be short, but it lasted forty-five minutes and when it ended the audience continued to chat and share stories with each other for another hour about how they were personally affected.

That talkback was a gift. What was meant to be an average discussion with notes for the playwright had radically transformed.

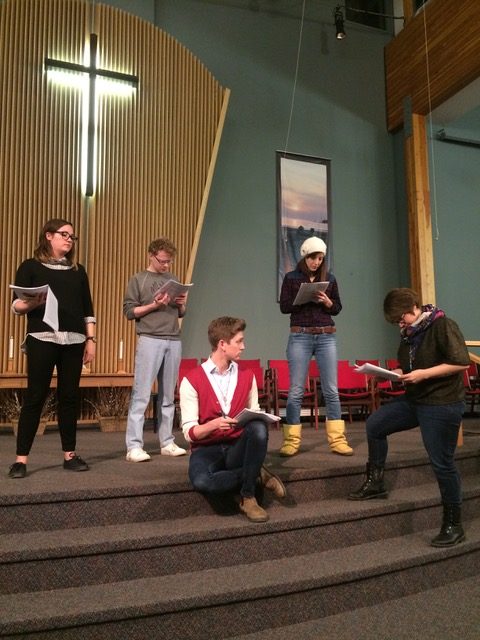

That summer, at the encouragement of my friends dramaturg-director Laurel Green and writer-activist Pam Rocker, I decided to remount oblivion with my own theatre company, Third Street Theatre, in conjunction with Hillhurst United Church for Calgary’s 2015 Pride Celebrations. We would present the script on the Hillhurst United Church altar and then invite the audience to stay for an extended time of conversation and sharing. With the addition of several new scenes, and an injection of hope in the play, something like a miracle happened in that church as we shifted to the conversation.

I would describe that evening as positively tense, intimate, challenging and healing. It felt like everyone’s walls dropped. I had shared a vulnerable part of my soul and in turn I was gifted with a room full of diverse people that didn’t all agree, sitting beside each other sharing their stories with no shortage of tears. I was emotional. I had spent a lifetime of being on multiple sides of the argument to arrive there in that room and somehow have given enough of myself that people wanted to share their hardships in thanks. It sounds reductive, but it felt like all of my pain and suffering in my journey were lifted and redeemed by that moment. It was there that I started to find my faith again. It was then that I found the show that I wanted to make. It was clear that this extended conversation wasn’t just an addition to the show, it was the second act.

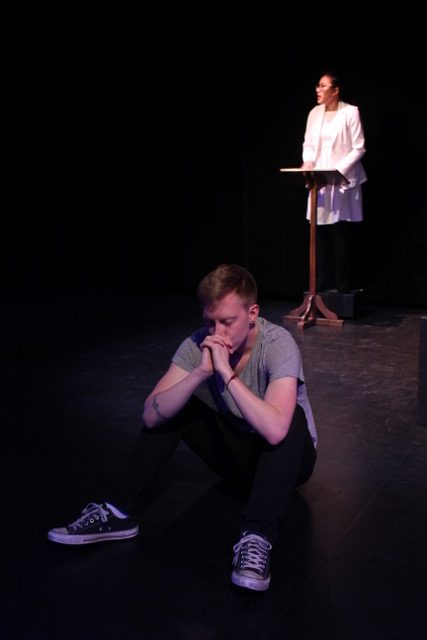

With Laurel as my dramaturg and director, a talented cast of Calgary actors, and support from all at Third Street, we designed oblivion to tour. We billed it as “a staged reading in two acts”. Act one, a staged reading with professional actors on the church altar using whatever furniture (pulpits, choir benches, crosses) is in situ, and then act two, a conversation with the congregations that includes the minister/pastor of the presenting church or community. And we always include an anonymous feedback wall with the show to make sure everyone feels they can participate. We have been invited to perform in Non-denominational, Presbyterian, Anglican, and United Churches.

At first my creative team was apprehensive about what doing this type of show would be like in a church setting. There were questions about language, content, and how to respect believers and their space. There was also the concern about the second act; would there be anger, arguments, people walking out? Would there be judgement on us, or worse, more condemnation that might lead to more harm for those in the audience. After the showing for Pride in Calgary, it was clear that this show wasn’t inciting anything but compassion for the story, the team and those in real life that had experienced this type of struggle. The fears were dispelled and my team started sharing openly and vulnerably about their own stories of processing God, sexuality, coming out, and how they related to faith as a result of oblivion.

I fondly refer to the tour as evangelizing the church with theatre, but it has done much more than that. It has been a tool to deepen understanding of how the church has excluded the LGBT community. It helps congregations move towards an affirming stance on LGBT inclusion or deepens the understanding of a community that has already taken a pro-LGBT stance. The performances are always public and the LGBT community hasn’t missed a chance to be included yet. The show is versatile and has toured as part of national queer faith conferences, played during Sex Week at the University of Calgary and even to a room of anxious, closeted conservative Christian students at Ambrose University. It is moldable, it is educational, and it is a step towards reconciliation between communities.

Over a thousand people have witnessed the show to date: atheists have gained a newfound respect for those with a deep desire for faith. Teachers have asked how we could show it in schools. Some in the queer community have let go of some of their animosity and fear towards Christians. Those who lost LGBT loved ones to suicide have found healing and peace. Allies have felt they can finally understand the complexity of the challenges their queer relatives and friends have had to endure. Even trans audience members have seen themselves in the story. It was amazing to witness Christians and queers alike acknowledging the negative roles they have played in stoking division towards each other.

Ministers have said the show is a catalyst that opens up a “sacred space” for dialogue “within which minds can be challenged and hearts touched” and that the more people that witness this, the better off we all are. For me, one of the most insightful comments about the show’s impact in bringing us together was from an anonymous post-it note that said, “Jesus would love your play and he would bring the wine to the after party!” Talk about Holy Communion! In my mind everyone in the audience is welcome at that party.

Isn’t this exactly what we need in our world? More chances to gather, share our remarkably different stories, digest and just be, together in the moment. I mean in the same room, not on the other side of a screen! Theatre does this naturally, but once the lights are up, the conversation goes internal or at best you discuss the themes with your date at a later moment. What about processing together with the strangers beside us, opening ourselves up to more than just our own opinion? That is scary. And that is exactly what we need when our go to has become the backlit media screens that connect us more to people across the ocean than our next-door neighbours.

This is the beauty of oblivion’s second act. It affords us what I believe we all need: an extra moment in time where we get to try to understand one another, to get re-acquainted with those breathing the same air. In doing so, we open up that ‘sacred space’ where we can find faith in each other. Only then do we get a glimpse of how all of our unique stories are actually wrapped up together.

As for this gay Christian theatre artist:

I will continue to use that title as a reminder that those identities are not mutually exclusive. I will keep my newfound faith and sit in the tension. I will bring oblivion to communities that desperately need to dialogue openly about this before more people are harmed. I will share my story with strangers because we are in this together and no one is immune.

We are all witnesses to each other’s lives, it’s time we stopped closing our eyes.