This is the first in a series of articles capturing the planned conversations and discussions at the inaugural Festival of Live Digital Art (foldA), in Kingston ON, June 19-June 21, 2018. Colin Clark writes about a conversation presented on the dock at Thousand Islands Playhouse titled “Think Different” between Clark, Carmelle Cachera, Brett Christopher, moderated by Remington North.

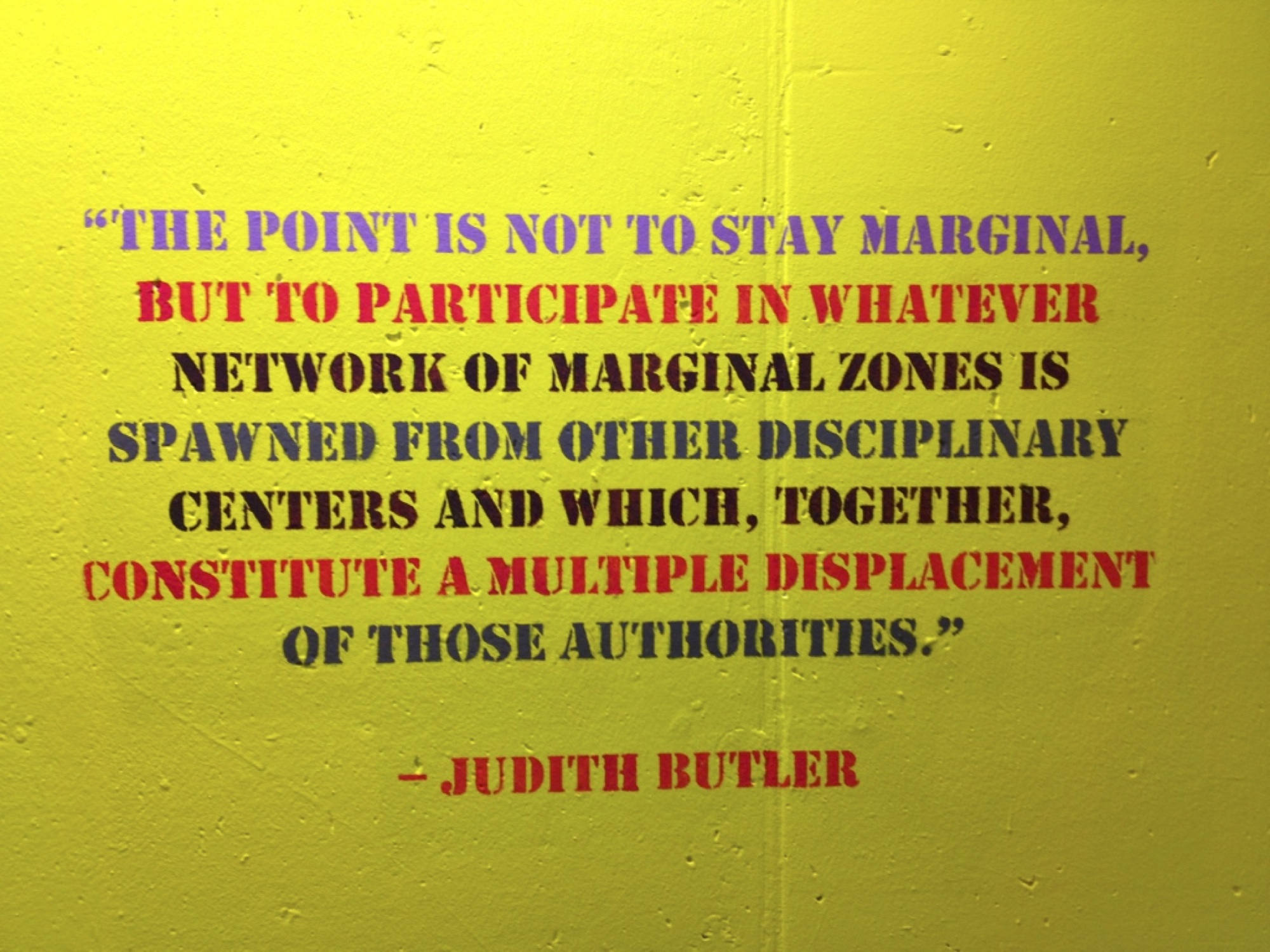

Today, I’d like to talk about the margins. The margins of the book we dreamily scribble and sketch in, the margins we’re relegated or confined to, or the margins we commit to and find our communities within. Can we trace a network of marginal zones—to find the possibility of new intersections among these margins, productive spaces for collaboration and creativity? Could these margins be the source of new ways of thinking and being in the world with technology? A source of innovation and of thinking not just differently, but diversely?

Digital technologies have an uncanny capacity to reconfigure our social relations—to collapse boundaries while simultaneously generating new margins and exclusions, even as they claim to tell a universal and utopian story. But it seems it’s always the same story, told over and over again as if it were a new story. It is worrisomely easy to read between the lines of this story and see how technologies are amplifying disparities in our society. Work, for everyone, is increasingly becoming sporadic, precarious, uncertain, and underpaid. Here, too, artists have been at the forefront. Gigs have become a whole new economy now—”We can’t pay you, but it will be good exposure.”

It’s not all so bleak, though. There’s another story, too. In the twenty or so years I’ve been doing inclusive design, I’ve seen the way technologies have opened up whole new fields of expression and interconnection for people with disabilities—social engagements that simply weren’t possible without technologies like instant messaging, the mobile web, or the internet of things. Artists, too, have found marvelous new forms of expression, of seeing and hearing and being in our bodies with technology.

Technology, as Ursula Franklin defined it so simply and clearly, is a practice; it’s “how we do things around here.”* This is to say, and perhaps I’m pointing out the obvious, that the ways in which we create our technologies—the techniques and values and social dynamics that we practice with, and invest within them—will have fundamental shaping effects on the kinds of technologies we can create, and on what can be done and expressed with them.

So much of today’s extractive “innovations,” I feel, are being formed from a myopic design culture, one which too often assumes that everyone is the same—or at least can be modelled in the same ways. That difference can only be expressed by a choice between products; that “users” are just passive consumers that can be modelled and predicted as what Katherine Behar calls “personalities without people,” data points in a social network’s advertising algorithms, unlatched from their context and temporality, with a logic all their own*.

So, if technology is, at heart, an expression of social practices, then I think we need to spend some time thinking through what kinds of practices, what models of sociality, are most important to us. And it seems to me that artists and storytellers are uniquely and sensitively attuned to precisely these kinds of questions. We understand that a story simultaneously creates a new kind of abstraction—a new possibility for being in the world—and also has the capacity to represent people in their wholeness and specificity.

In contrast, I’ve noticed that most technology design methods that are practiced in industry today tend to adopt certain outmoded anthropological and ethnographic narratives without question. Like the idea that a design researcher can be an objective, impassive observer of real-world practice, and that their primary role then is to expertly synthesize, extract, essentialize, and then model the diverse people they observed into a “persona,” or fictional character. But this kind of abstraction is storytelling cliché—it’s retelling the same story over again. As Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie says, “The single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story.*”

Technologies today are predicated on a fascinating and fundamental dichotomy: of designers and users. In its defence, this dichotomy might be a productive one, and it certainly seems to be familiar to us here in the theatre or in music or cinema, where we have artist and audience. But increasingly, this distinction strikes me as one that aims to keep us in our place, to a establish a hierarchy of those who have the power to create, and those who simply “use.”

Yet technologists, as I see it, have to make room for these new stories—to make space for the creativity of the people who use our systems, who make themselves at home in our technology environments every day. Everyone can be a creative contributor to the design process if they want to be and are allowed to be. But it takes some new and different ways of doing things.

Co-design is the process of designing with, not simply for. At the Inclusive Design Research Centre, where I work, we have been practicing co-design for a number of years, learning the hard way and the only way—by experimentation, by making mistakes, and by always asking questions. By asking the people on the excluded edges, or simply those who might otherwise just be “users,” to be part of the design process from the beginning, by asking them, “What role do you want to play in this process, and how can I help you?”

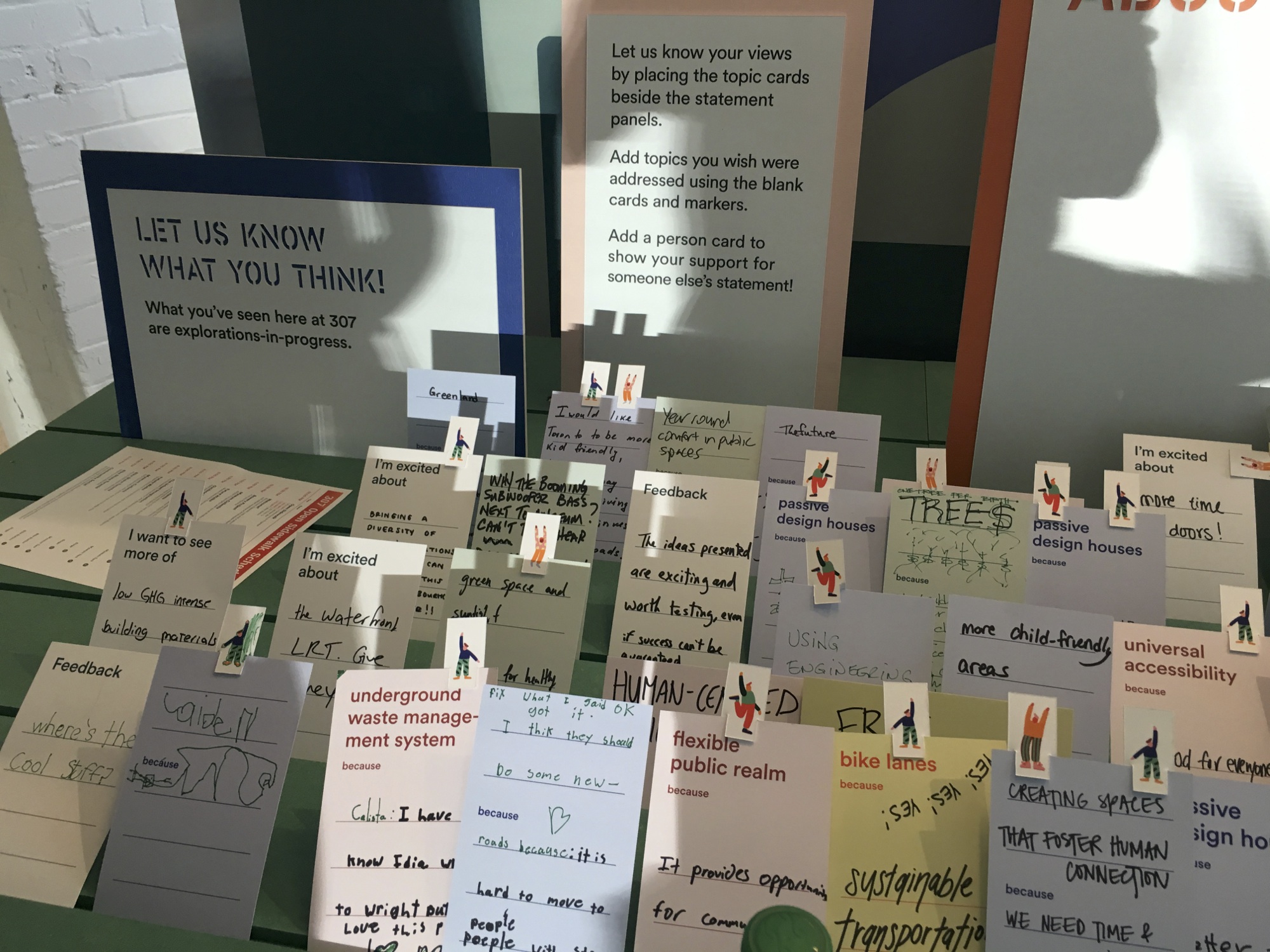

Co-design takes time; it requires diverse voices to be invited to the table; it needs to be tailored to the unique context and situation that a design intervenes into; and it demands that all participants have equal access to the information—plans and work in progress—that is essential for responsible decision-making and contribution.

Co-design has to be reciprocal. It isn’t about allowing people to participate, it’s about practicing in ways that are self-aware of the profound power and privilege that technologists have, and in finding ways to fully share and give up that power. It’s not enough simply to ask people for feedback—to “let us know what you think!” Participants in co-design need to know that their input, their ideas, have power and influence. Co-design demands the knowledge that your ideas will be heard, that they can have a direct influence, and that the mechanisms and processes by which they will potentially be enacted are clear and accountable.

The other aspect of the “co-” in co-design is community. Technical practice needs to be situated within the context of communities, especially those in which the participants have an opportunity to continue to be involved in the process, to feel a sense of autonomy and stewardship over the work they’ve contributed to. Fluid, an open source community that Jutta Treviranus and I started in 2007, has evolved as a community to support the engagement of people who might not feel that they belong, or would be welcomed, in the traditionally technocratic environment of open source software development. Fluid has, over the years, attracted a small and dedicated group of designers, developers, artists, users, people with disabilities, and others who are dedicated to inventing new ways to design collaboratively, and new software tools to support what I call “material systems”—software that you can change and redesign yourself, in connected ways, without needing to be expert programmers*.

As I said earlier, I think artists can uniquely help lead the way toward new technological practices—new ways of “doing things around here.” Artists, I think, are the ones who can best think outside, connect the margins, who are willing dream and do the things that seem might too weird, inefficient, or impractical to others. Artists can tell many more stories, from different perspectives—stories that are specific and whole, rooted in history and materiality, yet still full of abstract possibilities for new forms and social connections.

*Franklin, Ursula. The Real World of Technology. House of Anansi, 1999. p.6

*Behar, Katherine. “Personalities Without People.” The Occulture, March 21, 2018.

*Ngozi Adichie, Chimamanda. “The Danger of a Single Story.” TED. July 2009. Lecture.

*Clark, Colin. Insignificant Surfaces: Cinema, Systems, and Embodiment. MFA Thesis. OCAD University, 2016.