For the past 2-years we’ve been making a show at The Theatre Centre called This is the Point. It’s about love and sex and disability, and was created by a team of disabled and non-disabled artists. In my experience, most people aren’t so interested in hearing about disability, but they are interested in hearing about people. So let me tell you about the people involved.

Tony and Liz are a couple. They’ve been together for 13 years. They are funny, passionate, dedicated, and if you asked them, they would tell you they are horny. They both have Cerebral Palsy. It affects them in different ways. If you met them, you might not know that Liz had CP. In Tony’s case, it’s quite visible. He uses a wheelchair and is non-verbal. He communicates by spelling out his words on a letter board. When you speak with him, you read along, and you speak his words.

Christina and Dan (that’s me) are a couple. We’ve been together for 13 years too. We do not identify as having a disability, but our lives are very much shaped by it. We have two children Bruno and Ralph (and a third on the way!). Our son Bruno is 7. He likes music and wrestling, and he has Cerebral Palsy as well. Like Tony, he is non-verbal. Unlike Tony, he is still looking for a reliable method to communicate. We are working with him to do that.

The Theatre Centre’s stage is accessible but that doesn’t mean the building is. The rehearsal hall is sunken down two feet, so they built a ramp. And it turns out there’s a 6-inch step in the hall that leads from the dressing room to the elevator. So they built a ramp. How do we know that there are all these accessibility challenges? Because The Theatre Centre invited us in, and they accepted the responsibility of providing an accessible stage. If you make a space accessible you have to commit to making all the spaces in your building accessible. And the best way to do that is to actually invite artists with disabilities to work in your space. To see how the space works for particular people with particular needs. To make a commitment, for better, for worse, to figure it out together.

I met Tony through another project called What Dream It Was. Christina and I were interested in using our theatre practice to create opportunities for people like our son Bruno to create art together. We invited Tony to participate in the project. He said no. He wanted us to produce a play he’d written about his life. And we thought, here’s a guy who wants to express what’s inside of him through Theatre. This is exactly the kind of opportunity we’d want Bruno to have. We have to do this. So we met up and began to play. And he arrived with his partner Liz who would be assisting him. She said she didn’t want to be on stage, but here she is two years later rocking it out on stage.

When we started working with Tony and Liz, we knew we wanted to be on stage together. We wanted to find ways where we could be equally responsible for each other. I was not there to serve Tony. I was there to make a great show with Tony. We are responsible for each other, and we must disagree, discuss, and come to a path that we are inspired to pursue.

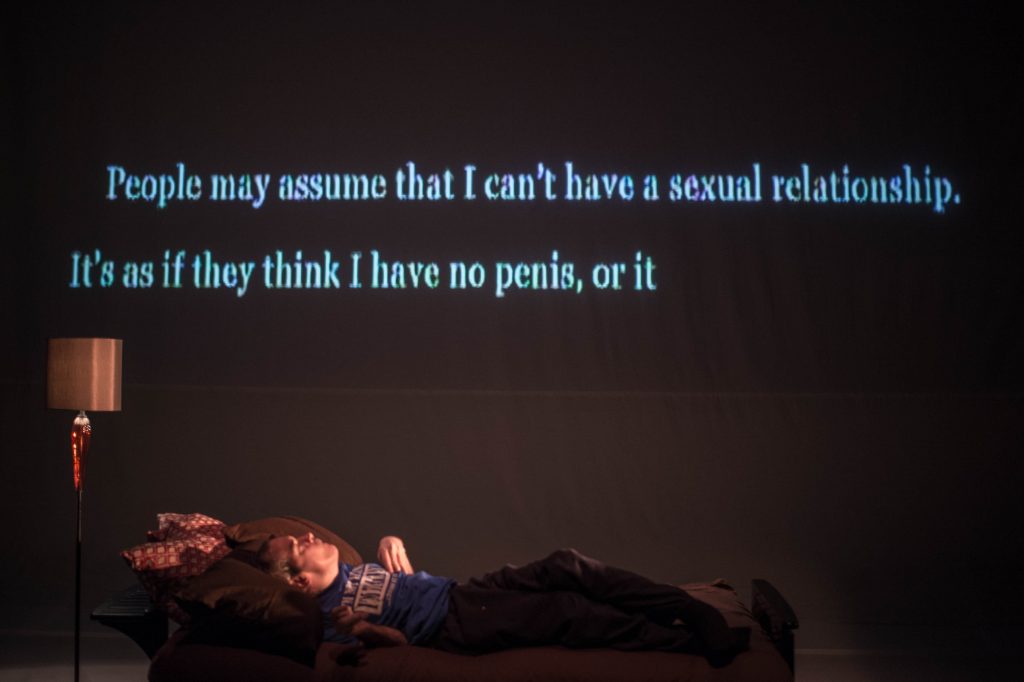

We started with Tony’s script that he wrote along with our director Karin Randoja. We tried to create scenes with dialogue between us. We made some really awful work. I say awful because we were trying to fit ourselves into something we’re not. Tony’s way of communicating is much slower than verbal speech, and we were afraid to take the time needed for Tony to communicate. We were playing by the rules of a verbal world. So we tried something different. By using a live feed camera and projector, Tony could speak directly to the audience. We would tell the stories this way. The length of time that it took to speak, suddenly became incredibly engaging. But where did that leave us folks on stage who communicate verbally? So we changed again, exploring how Tony’s communication could live on stage along with our highly physical approach. We began to find a form that fit for all of us. It’s a continuing process. We are never able to get it quite right, so we keep trying, we keep listening to each other, and arguing. It has led to a really interesting creative process and a deep friendship between us.

There’s a show called Kill Me Now by Brad Fraser. In its London production, the character of the disabled son was cast with a non-disabled actor. There was of course much discussion and controversy over this. In an op-ed in the Stage (which is also the forward in the printed play), Fraser defended the decision by writing in part:

That is not to suggest that disabled actors can’t do theatre, but that the way in which it is done will vary greatly by individual and role, and – in the commercial theatre at least – this will always come down to a question of time and money.

Unfortunately, I think Brad is speaking a truth. In my experience, people like the idea of inclusion, but aren’t always as keen on the reality. Theatre processes and structures aren’t built with disability in mind, so changing them can mean time, money and hard work. And these processes and structures can be so ingrained that one can’t even imagine how they could change them to be more inclusive. The perception is that there’s nothing they can do about it. It’s just the way theatre is made.

But what if there was something they could do about it? What if they opened up the process, and vision for how the story could be told?

First, it would give a disabled artist an opportunity to be on stage. Someone from an often marginalized community, an incredibly diverse community that spans race, religion, culture, orientation, class, but a community that shares the common experience of being excluded from much in their daily lives, that often face great barriers in gaining access to employment, services, transportation.

But secondly, it can make the work better because you have to change the way you work, you have to look for different solutions, and you make new discoveries that you would never have made otherwise. What seems like a limitation is actually an opportunity, and that realization can lead to a richer, deeper and more meaningful performance. It can lead to new processes, methods, ideas, images. It can challenge artists to push beyond their comfort zone, beyond what they know. Artists should be doing this. To not do it is artistically lazy.

It’s not a new idea. Well-known companies like Back to Back Theatre, Graeae Theatre, brought here by presenters like Tina Rasmussen at World Stage or the folks at Luminato. And closer to homeTangled Arts, Picasso Pro, Cahoots, Dramaway and the list goes on including community engaged work from companies like Jumblies Theatre, MABELLEarts, ARTS4ALL, and more. Inclusion is about being willing to change. Sometimes it means you don’t get what you want, or at least what you think you want. But then you find something together, and it’s better than you could have ever imagined on your own. It comes from who is in the room, our collective imaginations, our beautiful limitations, and it comes from how we hear each other