My job at Canada’s National Arts Centre allowed me to work closely with and learn from several artists in Canada’s Deaf, disability and Mad arts community at the Summit 2016, a three-day event held by the NAC in Stratford in April. It was because of this privilege that I was invited by British Council Canada to train as an Access Activator Consultant on Relaxed Performance, an aesthetic of performance presentation designed for those on the autism spectrum, people with sensory sensitivities, or access needs related to involuntary noise or movement. As part of the training, I was also invited to the Unlimited Festival in London and Glasgow, the largest Deaf and disability arts festival in the world.

In Toronto, at the initial Access Activator training with Kirsty Hoyle, Founder and Director of London-based Include Arts, I was introduced to the “social model” of disability. Coined by UK academic and disability artist Mike Oliver in 1983, the social model suggests that disability is caused by the way society is organized, rather than by a person’s impairment or difference. It accepts that society has created barriers that restrict life choices for some people, disabling them, and suggests seeking to remove barriers and enable people. I remember Alex Bulmer, one of the Artist/Leaders at Summit 2016, talking about how much more free she feels in the UK as a person with a disability. It was with all this in mind that I set off for London; I was on a mission to witness some access, UK style.

From the moment I landed at Heathrow, I started looking for people with visible disabilities. I began noticing them in shopping malls, restaurants, pubs, markets, museums, theatres, nightclubs, doing the same things I, an able bodied person, was doing. I also noticed it was much easier to find elevators and ramps- there were icons, signs, raised floor tiles and audio descriptions that provided guidance on the street and in the tube. Accessible cabs were at the ready from London to Glasgow, enabling a multitude of activities, at any time of day or night, for everyone. Even the television channels had signed interpretation pop up in the corner of everything from the soaps to news to reality shows. Compared to Ottawa, the access seemed endless. I began to understand what Alex was talking about.

The Unlimited Festival is an incredible legacy of the London 2012 Cultural Olympiad, featuring a broad spectrum of works in dance, music, theatre, performance and visual art by people with disabilities. It has a dynamic industry component of discussions, readings, workshops and networking events. Unlimited is also a publicly funded, self-administering granting body that commissions and supports production of works by artists with disabilities thanks to Arts Council England. Many of these projects are programmed at the Unlimited Festival and tour in the UK and internationally.

In addition to Unlimited, there is also a considerable number of fully or partially funded Deaf and disability arts theatre companies in the UK that regularly produce new work, and many of these are led by Deaf or disabled people. The Agent for Change initiative provides placement for artists and art administrators, providing more opportunities for Deaf and disabled people to work in leadership roles in major cultural institutions.

Around the country, access formats like signed interpretation, audio description and Relaxed Performances are becoming increasingly common in the performing arts. Disability is being considered in cultural spaces, impacting their designs. Some theatres are even investing in research and development of technologies, like captioning or hearing assist services, that better serve performance platforms. Marketers are promoting accessible performances to primary audiences and communicating their accessibility and/or potential barriers clearly. Deaf and disabled audiences are being spoken to directly through signed introductions, described web pages, easy-read versions and diverse imagery.

Visionaries like Jenny Sealey of Graeae are pioneering embedded access as an aesthetic, building sign, description and captioning into a production in tandem with creation, rather than bolting it on after the fact. Theatre companies, large and small, are making adjustments like adapting rehearsal hours, production time frames and methodologies, as well as considering the effects of ceremonial practices and support mechanisms. Organizations are investing in staff sensitivity training, sign language instruction and sensory audits. Theatres are creating front of house and box office policies that support access, and working with other companies to compare accessible performance schedules to avoid conflicts and create opportunities.

The Ramps on the Moon project is consortium of seven venued theatre companies sharing large scale touring works featuring Deaf Artists and disability artists, and they have an upcoming tour of Tommy. Major companies are employing disability artists in their core works, like the National Theatre’s recent Threepenny Opera, and presenting new work made by Deaf and disability artists and by organizations like Graeae. Agencies and networks for artists and audiences around the UK have sprung up to share ideas, resources and access opportunities like disabilityarts.online. Within rehearsal halls, on stages, and in film and TV across the UK, artists with disabilities are being supported and producing work in great ways.

Unfortunately, just like our own country, funding for basic services for people with disabilities continues to be a challenge in the UK. Despite fairly robust access legislation governing the entire UK (which does not exist in Canada) and an emphasis on arts funding for Deaf artists and artists with disabilities, provisions for day to day needs and support services have seen recent significant cut backs. For artists with disabilities in the UK, just as I have heard in Canada, advocating for day-to-day needs and support can be overwhelming, leaving little time or energy for artistic endeavours.

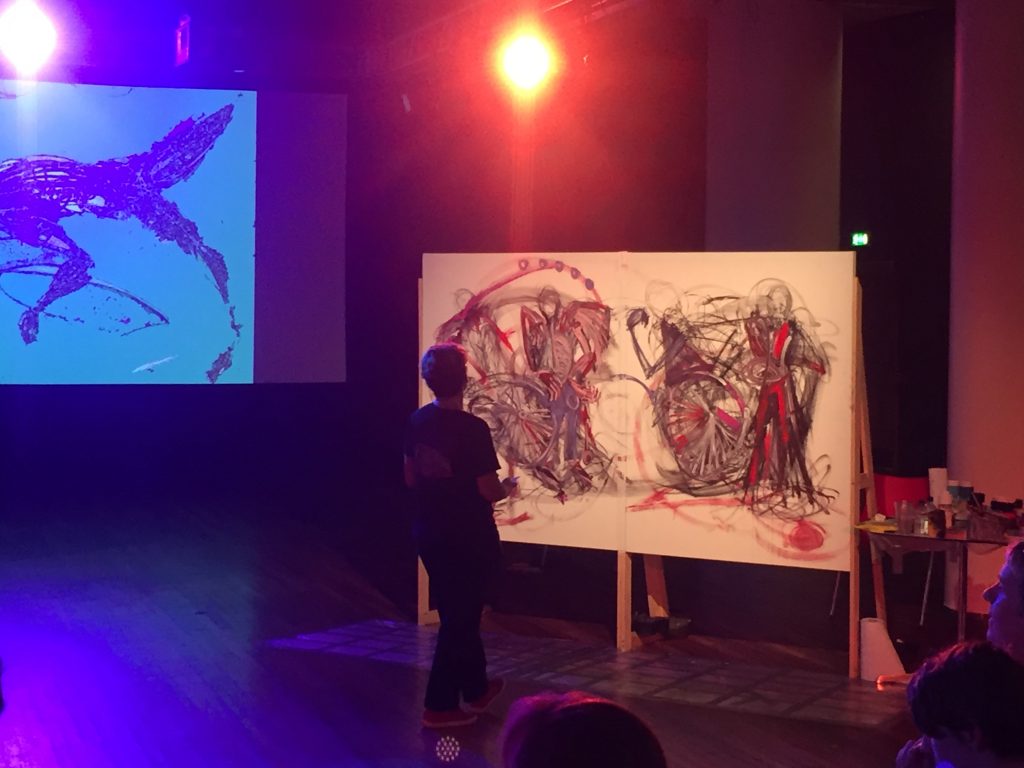

Yet still, theatres are including access provisions in global budgets to remove perceived fiscal barriers to providing for the needs of Deaf artists or artists with disabilities in production. Well-supported commissioning of new works from the Deaf community and people with disabilities and inclusive casting practices are also enabling artists to put down the activism placards and just be great artists achieving their artistic potentials. Deaf artists and artists with disabilities are starting to lead the way – fostering independence, ownership and a stronger voice alongside able bodied allies. These gains in equity are spawning significant innovation, greater diversity and fantastic creation.

I am looking forward to hearing the conversation in Canada as I head into the final phase of the two-year Cycle with the NAC, culminating just before Canada Day. The Study 2017 and the Republic of Inclusion, are two events that will bring together dozens of leading Deaf artists and artists with disabilities and allies from across the nation. As we turn the page on 150 years of history, I wonder what lies ahead for Canadian diversity and equity, particularly in the Arts. At the NAC, we are working towards inclusion in the near term, playing with embedded access and featuring Deaf and disability artists in our upcoming productions of A Christmas Carol, and Brad Fraser’s Kill Me Now. Perhaps, as Gord Downie said at the recent Secret Path performance at the NAC, the way forward is together, for all of us. Perhaps together we can all be unlimited.