I was recently sharing my love of Agnes Obel’s new song ‘Familiar’ with a friend, and I found myself realizing something interesting: I have a weakness for strange vocal manipulations in music, especially those that skew the perception of the singer’s identifying vocal qualities. Hearing a voice being skewed beyond its usual range, tone, and flexibility is a truly disorienting experience. Singing is something we often consider such a natural ‘human’ activity, and vocal production is bound tightly to the body performing it and the perceived gender of that body.

Performing with most instruments has at least the potential to be a non-gendered experience. In a recording or performance where the performer is not seen, the listener has no way of discerning or assuming that performer’s gender identity. In theory, all genders have an equal ability to play an instrument, though most instruments are manufactured for male bodies. Singers, however, are required to have their gendered bodies on display no matter what. Their roles, repertoire, and identities as musicians are intertwined with the pitch of their voice. Choirs and opera singers are so strictly divided on lines of ‘men’ and ‘women’ that even when the range of their voices is similar they are categorized based on gender. Sopranos and Altos are women; a man with a voice in the range of a Soprano or Alto is called a Countertenor.

Voices that are read as female are often are met with less respect than voices read as male. Singers Grimes and Joanna Newsom have both expressed disdain for having their music regularly described as ‘childlike’, and themselves infantilized by critics because of the high pitch of their singing voices. Female voices in rock and punk music are often perceived as being ‘shrill’ and ‘annoying’ when performing in a similar ‘untrained’ style as many highly regarded male singers in the genre.

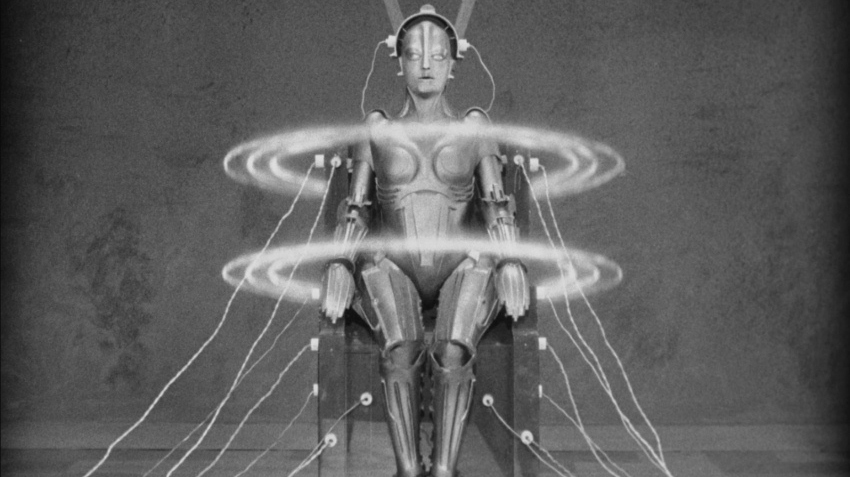

In the digital age, the possibilities to mechanized voices have become increasingly prevalent. Though singing and speaking are considered to be organic human expressions, the robotic voice has become a part of daily life (appliances that speak to us), popular culture (science fiction films, video games, and books describing sentient machines), and experimental art. Robots and female bodies have an interesting history in western culture. Fritz Lang’s 1927 masterpiece ‘Metropolis’ portrays a terrifying female-bodied robot blending together two of society’s most feared things; unbridled dangerous technology and rampant female sexuality. Many automated voices are female, as are artificial intelligences in video games and films. Casting female voices in these roles supports the conception of women as subservient and ‘less than’ or ‘other than’ human, whilst also pairing their speech with potentially dangerous beings with infinite knowledge.

Digital music technologies, such as vocoders, vocaloids, and autotuners, allow singers to escape from the confines of their physical bodies and abilities. Musician Susumu Hirasawa, famous for creating the soundtracks for Satoshi Kon’s films, has done innovative work in vocaloid production on his way to his ultimate goal of creating all of his complex music without any performers or personnel other than himself. Brother/sister electronic music duo The Knife play with gender in their music with their appearance, lyrics, and vocal manipulation. The siblings often perform and are photographed in masks or matching makeup, skewing the audience’s perception of which one is the ‘man’ and which is the ‘woman’. Singer Karin Dreijer performs both ‘female’ and ‘male’ voices (and even occasionally ‘child’ voices), sometimes all in the same song. Through technology, Karin’s voice is thus able to transcend its ‘femininity’, and break into parts of our psyche unlocked by ‘male’ tones. She is able to converse with herself and her listeners across ages and genders, her voice becoming more of a playable, non-gendered instrument than a product of her body.

Human beings create technologies to extend their bodies; to make them stronger, smarter, and faster. Digitization of musical effects does not ‘de-humanize’ musicians, it instead allows them more space to expand their ideas past their own physical characteristics and limitations. Technologies for synthesizing and editing voices are beginning to facilitate a breakdown in the strict gender roles that pervade vocalists and music containing singing. By de-gendering song we are not removing it from its status as a basic human activity, but instead furthering its potential to give a wide variety of individuals a multitude of ways to express their emotions.