A Bit Fit

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

SWS Podcast 05

CONTACT US

Twitter #SWSpodcast

LINKS TO THINGS WE TALK ABOUT

This Moment is an Invitation

Performers (L to R): Penny Couchie, Julie Tamiko Manning

* World Premiere, Firehall Arts Centre, Vancouver, 2004

This moment is an invitation: An open door leading to a cup of tea and a bowl of homemade soup.

This Moment #1: I am a child, a teen, a young woman, listening to my father speak of our Beginning – how the four corners of the world were folded up and inside all that rolling mud, woman and man were made to walk side by side, as equals; the only difference being that women are the Life Givers. I am made in the image of our Mother who, as the Earth, is responsible to sustain and nourish. My responsibility is to contribute to this cycle of care. Women’s knowledge is sacred; what we know will ensure man’s survival. A woman’s power comes from the earth. Pants interfere with this connection, which is why we wear skirts for ceremony. “In a sense, feminism wrecked women’s relationship to their own power,” my father says sadly. “Men have forgotten their place.”

My introduction to my female-self was ceremonial. My introduction to my artist-self was less about affirming a woman’s power and more about learning to accommodate, acquiesce to, and affirm a euro-driven hierarchy along with phallocentric models of performance, criticism, and theory. The act of melding these ideas into my artistic practice has become a political one. This is a feminist impulse. Each project is an opportunity to address the tension I experience inside this political act.

This Moment #2: I am a woman, one of two artist/ playmakers invited to teach Indigenous performance methods in a small Eastern European country. My colleague, who is established relative to my emerging, is also Cree. It becomes apparent that his intention is to lead. My role seems to be to stand at his side as silent witness. My frustration grows. The day after our second session, we walk as he reflects on what he hopes people learned, what I witnessed, and whether he over-stepped in any way. It hits me: our process in this studio is not just artistic, it is defined by our cultural relationship.

In this scenario, my cultural responsibility as a woman is to ‘hold the room’ – to support my colleague and keep him accountable, and to ensure protocols are followed so that the space is respectful and inclusive. I know this role well – as my father’s Helper. Cultural connections become foremost in defining my artistic process. For people to be equal, they don’t have to be doing the same thing. Our power is different, not ‘more’ or ‘less.’

BLAM COLLECTIVE::

Performers: Lisa C. Ravensbergen, Darren Dolynksi

* work-in-progress showing, Talking Stick Festival, Vancouver, 2011. Photo Credit: Chris Randle

Understandings of “feminism” are as non-consensual as understandings of “Indigenous perspectives.” The way feminism reflects itself in my work is as unique as the way I interpret and practice my culture. My feminist art practice exists even if it’s not recognizable or aligns with the normative assumptions about what feminism is. Each project takes me one step farther away from an obligation to measure the worth of my own feminist practice against a politik that does not always feel authentic to my cultural practice.

Performers (L to R): Aura Carcueva, Falen Johnson, Maria Christina James, Julie Tamiko Manning

* Native Earth Performing Arts, Toronto, 2007. Photo Credit: Nir Bareket

This Moment #3: I am a mother, a writer in the throes of life, haunted by another draft that isn’t going anywhere. My dramaturg has ridden her bike across town and seventeen blocks up a mountain so she can sit at my table and discuss my play. She sips her tea as I prepare our lunch – a soup that will later warm my family’s bellies. I apologize for everything; for not working fast enough, for ineptly writing simple scenes, for making her wait, for the mess of my house, for the effort it took for her to get here – all so that I can more easily pick my child up from school. We pause. She quietly asks about my writing and process. I tell her about this world of three women I am creating. It is a story of stolen children, lost identities, and a grandmother who is really a lost owl spirit, waiting for redemption. We find this rhythm that works; a ritual guided by the slicing of my knife, by the wiping of my hands, by her tasting of the spices, the stories of my family, the psalms along with my father’s traditional teachings – all in symphony with her internet research. Here I use my knowledge to embody this role now set inside a familiar domestic ceremony – one she and I will return to time and time again over the next year or so. She calls it “kitchen dramaturgy.” I accept this. I see how this now – this too – is my work: to be witnessed in the melding of my living-life and artist-life, as only a woman can.

Our first impulse as creators is to witness. Our primary action is to respond from our artist-selves. In this process, we also name our other-selves – the woman, the woman of colour, the woman empowered. I can support a process as *I* must – as a First Nations woman or not. It means that my work inevitably flips Aristotle the bird. Women speak the words I write, and dance the dreams I tell. Ceremony lies at the root of every question. I mix worldviews in an ancient pot and stir it until the flavours assume their own temper. I discover what I’m making as it’s being made. And I share it as best I can.

Acknowledgements: Walter Cook, Elaine Avila, Heidi Taylor, Dylan Robinson, Jeff Harrison, Isaac Thomas. Chi Miigwetch – Thank you so much for your guidance and assistance.

Do artists have a responsibility to be feminists?

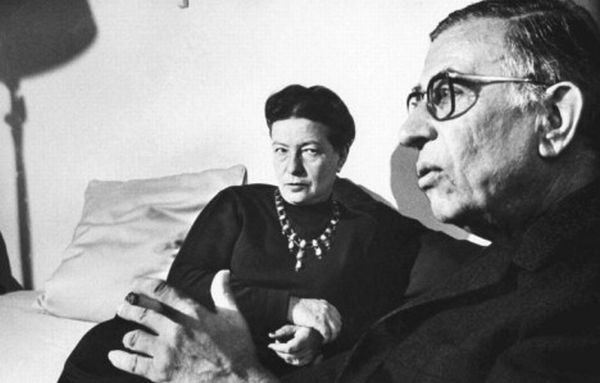

I’m going to have to acknowledge from the outset, here, all the conspicuous and morally ticklish not-so-niceties which are necessarily involved when a grotesquely privileged, white, heterosexual, cisgender (I’m sure someone will correct my use of that particular neologism), Canadian male writes about the problems of feminism in art. This is not intended as irony. Doubtless I place myself squarely in the sights of a particular kind of lefty scorn, appropriation-of-voice-wise, to say nothing of the dubiousness of my targeting (isn’t there a tag in The Second Sex about it not occurring to a man to write about what it means to hold the condition of being a man in society?). Well, all’s fair in the gender wars. I admit my undeserved privilege and surrender the field.

There are (at least) two ways to consider this question, and they’re interrelated but crucially different; on the one hand is the issue of feminist entelechy in the theatre world – i.e., the quantifiable by-the-numbers stuff about women’s gross underrepresentation among the ranks of regularly produced playwrights, directors, and routinely hired ADs – and on the other, more ephemeral questions of feminist aesthetic: what is a feminist play, and do we have a moral responsibility to make them?

The first issue is enjoying a long-overdue vogue in the theatre community’s rank-and-file; vide the recent “Summit” conference in DC, and the Twitterverse’s real-time tweet-slap of Round House Theatre AD Ryan Rilette for some rather dodgy comments he made about women playwrights. The second is somewhat more obscure, and I think deserves to be interrogated very seriously. I recently wrote a blog post responding to Darrah Teitel’s criticism of Michael Healey’s script Proud on the SpiderWebShow Feminist Issue 1.0. I was interested not in the accuracy of that criticism, but in the ethical/aesthetic presumptions which underlie it. I continue to be so; as a writer who has myself made conscious effort to write big parts for women, the fear of the “misogynist” label is never far from mind. This is not the ideal condition under which to write. I quoted on my blog, and quote here again, Ms. Teitel’s friend Adam Nayman:

Representation of women with power are as problematic as representations of women without, mostly because they are written and directed by men.

Double-binds are a particular neurotic cathexis for me, but few yield the kind of artistic despair this does. Nayman is of course correct – but what then? Should we not write them? And what, actually, makes these representations so problematic, other than just the fact they were written by men? There are reasons why the Barthesian tradition advocates the reading of texts anonymously (technically, advocates “The Death of the Author”). The moral/political baggage we bring to a text when we know its supposed “source” necessarily colours our reading – this is as true for the critic who savages a novel because it was written by a woman as it is for interpretations of female characters written by men.

Now before my inbox gets inundated with hate mail, let me just say that this does not at all mean that those readings are wrong or invalid. Quite the contrary; for someone to say that a play is misogynist is a perfectly good and probably defensible interpretation. But this cuts both ways – that is the fundamental problem of interpretation in art, and it makes it extremely difficult to create aesthetico-ethical prescriptions.

In other words, if it’s true that negative portrayals of women in art can and do lead to negative treatment of them (and that sure seems true to me), it seems, on its surface, logical that we ought to affirm the principal that writers have an ethical responsibility to create characters which adhere to feminist ideals. But here, I think, we reach an impasse. What would such characters be and look like? Who is prepared to offer and defend such a schema? And how do we reconcile this moral principle with the fundamental aesthetic problem of what Barthes called the “irreducible plurality” of meaning?

This is fascinating question for a writer like myself because it demonstrates what I’ve always believed to be true: that what seems like just abstruse and cerebral semiology has, in fact, real-world ethical implications. Aesthetic inquiry does not dwell just in the suburbs of academics and the idly curious, but is in fact crucial for better understanding art’s place as a political and cultural institution.

Even if you aren’t convinced by the theories of Paul de Man or Roland Barthes, it seems (at least to me) hard to deny that we can’t define a feminist aesthetic purely through negation. If we’re going to affirm that artists have moral responsibility in their art, it is not enough to simply address a trillion particulars and deem this or that “misogynist.” If we’re going to be prescriptive, then we have to be specific. What is a feminist aesthetic?

This seems an unanswerable question to me. Perhaps my admittedly rather glacial processes of intellection just aren’t up to the task. Nevertheless, however much I might like to say that we should expect artists to lead the vanguard of moral clarity not just as individuals but in their art, I cannot. The cliché that art is better at asking questions than answering them turns out to be true: as Peter Handke once wrote, “[theatre is] no good at all at when it comes to suggesting solutions, at most it is good for playing with contradictions.” These contradictions are what facilitate conversation, what foster dialectic, what gives rise to righteous rage. There were fistfights in the lobby after the premiere of Oleanna, a play many – including myself – have called “misogynist.” But misogynist or not, it mattered to the audience, it moved them, made them feel far more intensely than, say, a film like 12 Years a Slave, which for all of its earnest poignancy and moral clarity is ultimately a work of art that challenges the audience not one jot. Yes, slavery is bad. Thanks. So too is misogyny. But I’m not sure I go to the theatre or the cinema to be reminded of this. Moral prescriptions for the theatre are as deadly whether they come from the right or the left.

This is not an appeal to moral relativism in art, but rather an observation of how the interpretive process of art tends to work. I certainly would never wish to say that reviews like Teitel’s critique of Proud shouldn’t be written – in fact, the opposite. Teitel’s review is a really interesting and useful work; I’m merely suggesting that, for example, perhaps the very fact that a play like Proud can inspire such a response makes the play worthwhile, that controversy and moral ambiguity – even moral confusion – are not deficits in a work of art, but the very things that make it interesting and valuable.

Might a “feminist aesthetic” mean an aesthetic which embraces such controversy, which thrives in it?

Gender Equality in the Classics

Women in Canadian theatre are an oppressed majority, and it’s everyone’s problem that a group of people who make up 51% of the population and 59% of audiences are still underrepresented onstage and backstage*. I am arguing for an active approach to gender equality in theatre. Even if your company’s mandate is to produce classical plays by “dead white guys” and you have a mostly male ensemble, you can still play a part. If artists continue to assume that it’s “someone else’s fight”, this problem won’t be resolved soon. In order to achieve gender parity in theatre we need to get all theatres involved (not just self-branded “feminist” companies), we need to start telling more “people’s stories” as well as “women’s stories”, and audiences must be made aware of the disparity so they can join the conversation.

Many theatre creators focus on increasing the number of “women’s stories” onstage. While I certainly agree that we need more plays written by women and with female creative teams and casts, that is only part of the solution. The term “women’s stories” is also limiting; referring to all work that includes the perspectives and experiences of women as “women’s stories” suggests that plays with female characters are a niche market. Furthermore, the term implies that stories about women are separate from stories about men, which actually re-ingrains the gender binary. The general branding of “women’s stories” is what leads to seasons with one all-female show and five more shows that hardly involve women. This is connected to the larger cultural concept that women can identify with male protagonists, but men cannot identify with female protagonists; a concept which is played out in theatre when some directors happily produce 400-year-old plays about murderers and kings set 1000 years ago on a different continent, but the same directors express hesitation about “connecting with” the characters in female-driven plays. As well as producing more “women’s stories”, theatres should find ways to transform some of the many “men’s stories” they produce into “people’s stories”.

Theatres’ desire to change can often be hindered by financial concerns. There are many well-known, beautifully written, male-authored classical plays that feature mostly/entirely male characters. These plays often have better name recognition with audiences, making them less of a financial risk. However, a company with a season full of classical plays can (and should) still play a role in gender parity. Most obviously this can be done through the inclusion of women (and people of colour) on the creative team, and through colourblind/genderblind casting. While non-traditional casting might not make sense for all plays, it’s important to evaluate whether this kind of casting actually doesn’t work in your production, or if it’s been dismissed for a superficial reason.

A recent example of genderblind casting is Peter Hinton’s production of The Seagull at the Segal Centre this month, in which Diane D’Aquila played the role of Sorina (originally Sorin), giving the show a balanced cast of 5 women and 5 men. Another Hinton production that comes to mind is his 2008 staging of Taming of the Shrew at the Stratford Festival in which Lucy Peacock played a female Grumio. The Festival also produced Miles Potter’s Richard III in 2011 starring Seana McKenna. In these stagings, women were given more stage time and agency without the productions being branded (one might even say “dismissed”) as “women’s stories”- although whether that is because of the male directors, the fact that only one role was switched in each case, or the superstar actresses involved is up for debate.

Some directors who do not engage in genderblind casting suggest that audiences aren’t invested enough in gender equality onstage, and would be confused by it**. However, if audiences aren’t vocal about this issue, it’s at least partly because they aren’t aware of the inequality onstage and backstage. Growing up watching theatre, film and tv, audiences have been trained to accept mostly-male casts as normal. Theatres should take responsibility to inform their audiences about the gender inequality (or equality) in their productions.

Even with a play like Waiting for Godot (which legally cannot be performed by women), theatres can still contribute by raising audience awareness. One strategy that could be used is the creation of a basic notation system in theatre programs- sort of a diversity “report card” in the vein of Sweden’s new feminist rating system for films . This system could be a section of the program that breaks down statistics about diversity on and offstage, including the number/variety of women (and people of colour) represented onstage; and how they are represented. This system would increase audience awareness about gender imbalance, and could be used to track progress over seasons.

In addition to a program notes system, there are many other ways to encourage feminist dialogues about a production. For example, to complement classic plays in their seasons, theatres could stage readings of a feminist/female playwright’s adaptation (ex: a reading of Djanet Sears’ Harlem Duet to complement a staging of Othello). Another way to inform the audience could be creating a lobby display or website page that looks at the play’s history/characters/themes/ from a feminist perspective.

This article is not meant to discredit theatre pieces that are “women’s stories” or “men’s stories”, both of which are necessary and important in a balanced culture. However, whether or not it is intended, companies that choose to produce seasons of only “men’s stories” without comment are contributing to the symbolic annihilation of women. If theatre creators of all genders can work together to create more “people’s stories”, as well as “women’s stories”, and invite audiences to join in the conversation, the problem of gender equality in theatre might become a problem of the past.

*Anyone interested in more detailed statistics should check out Rebecca Burton’s report “Adding it Up: The Status of Women in Canadian Theatre“.

** There are many other reasons, of course, but I could spend a whole article on them alone

#CdnCult Times; Volume 2, Edition 7

Lots of #feminism talk lately @worldstage @SpiderWebShow etc. Curious – what term means to u? does it get your back up? #Cdncult

— FeverGraph Theatre (@FeverGraph) February 13, 2014

After significant interest in our first feminist edition, it became clear three articles could only scratch the surface of the issues it brought up.

After the first one, Keavy Lynch wrote about some of the ideas that were raised – so we invited her back to elaborate upon these thoughts. Alexander Offord also responded to one of those articles – you will find his expanded ideas here too. Lisa C. Ravensbergen completes the issue with some compelling thoughts on feminism from an indigenous cultural perspective. Feminism is back. On #CdnCult Times at least.

Michael Wheeler

Editor-in-Chief: #CdnCult Times

Whose Revolution?

On January 12 I flew to Cairo, Egypt, as part of the Theatre Centre’s Tracy Wright Global Archive commissioning project. The project was dreamt up by artistic director Franco Boni and artistic director in residence Ravi Jain, and inspired in part by a bequest from long-time Theatre Centre-based artist, and all round avant-garde superstar, the late, and much revered creator/performer Tracy Wright. Apparently Tracy believed deeply in the importance of artists traveling other places, and investigating what they don’t know, especially when they’re in that great big chasm of mid-career, which I think for many of us means: successful enough to keep making work, and almost never having enough time to think a step back and consider the track that’s gotten you onto that particular work.

I never knew Tracy, but pretty much every artist I love up close or admire from a distance speaks about her in the awed tone that we tend to reserve for folks we consider an actual genius. In honour of that genius, the Theatre Centre asked five us of (myself, Jani Lauzon, Nadia Ross, Daniel Brooks and Denise Fujwara) to each propose a place in the world we’d like to go, and a question we’d like to investigate while there, in whatever terms we might set for that investigation. I chose Egypt, where my father was born and raised, and where I’d previously been once in my life, in December, 2011, when my wife and two sons and I met my Egyptian family for the first time.

I never knew Tracy, but pretty much every artist I love up close or admire from a distance speaks about her in the awed tone that we tend to reserve for folks we consider an actual genius. In honour of that genius, the Theatre Centre asked five us of (myself, Jani Lauzon, Nadia Ross, Daniel Brooks and Denise Fujwara) to each propose a place in the world we’d like to go, and a question we’d like to investigate while there, in whatever terms we might set for that investigation. I chose Egypt, where my father was born and raised, and where I’d previously been once in my life, in December, 2011, when my wife and two sons and I met my Egyptian family for the first time.

My question: what is a revolution? Or, what does it mean, to have had one, three years after the fact? Or six months after the fact, if you ask some people, who consider the toppling of Muslim Brotherhood president Mohamed Morsi – generally accepted to be the country’s first democratically elected leader – in June, 2013, as the real revolution.

When I arrived in Egypt – on the eve of a national referendum on a new constitution, the country’s third such referendum (and seventh national vote) in 3 years – I had my family, who had agreed to speak to me, both about my dad, and their feelings about the revolution. I also, through a young filmmaker cousin and a friend in Vancouver had potential, but vague, connections to a series of Egyptian intellectuals and artists.

By the time I left, on the day after the third anniversary of the January 25 revolution – and having just witnessed my first car bomb – I had interviewed about a dozen people: April 6 Revolutionary Movement affiliated female journalists who have started their own online news site, in the face of real danger that the government will arrest or shut them down; a famous Egyptian painter who sat on the committee of 50 who wrote the most recent constitution; a theatre artist who goes into villages and writes songs with groups of villagers about whatever they want to write songs about; the artistic director of the Downtown Cairo Arts Festival; my aunt, who is 80 years old and has seen my dad, her brother, once in the last 54 years, for about five days, in 1997, the one time he’s been back to Egypt since 1959, and several others.

I won’t pretend those interviews make it possible for me to understand much about what’s going on in Egypt. I will say, though, that it’s a lot more complicated than any of us in Canada or the west are able to understand. Of course it is – that’s obvious. But it was also a real reminder to me how absurd it is for any of us to read any news about another place and think that somehow that means we could know enough to pronounce about what is actually occurring. That in and of itself might be a colonial impulse , which I’d argue is a very natural and human impulse. But over and over again, with a couple of exceptions, people I talked to asked me to tell my compatriots in America (yeah, whatever) to PLEASE LEAVE US ALONE. “We are poor,” my Coptic cousin priest Marcus told me, “But it is our poverty. And we are ok with this.”

Many also expressed real concern about my safety, as a Canadian, in Canada, because of this winter’s “polar vortex”.

I’m not yet in a position to coherently summarize my experience yet. I don’t have a ton of time to write this, or a ton of room on this blog. What I can maybe do is show you some pictures, to try to give you a sense of the territory that currently interests me.

Cairo rooftops. Understanding Cairo: Logic of a City Out of Control, a terrific book by a Cairo-based urban planner David Sims, charts the miracle of urban growth in Cairo, in which 80% of new development happens outside official government sanction, and yet still manages to provide safe accommodation for millions, and connect to municipal water and electricity. But my relatives and many other westernized Egyptians bemoan the degree to which the city has decayed over the last 30 years. Though the building decay (and ubiquitous piles of garbage) in the city feel typical for an early 21st century developing country with a exploding population, when my Dad left in the early 60’s, downtown Cairo was definitely much tidier. In1959 the country’s population was approx. 27 million. Today it’s close to 80 million, and is growing by a million every 10 months.

My cousin Marcus “the priest”, also named after our mutual grandfather at his Coptic Church in Garden City, the embassy district in the western section of downtown, bordering the Nile river. While interviewing Marcus, I was able to tell him the story of my sister, who was put up for adoption by my parents in the early 1960’s, and then came back into our family in the mid-1990’s, when she contacted my mum. Though he was vaguely aware of the story, no-one had ever sat down and talked him through it. His reaction was moving and hilarious. “It is something different!” he said, half-laughing, half-stammering. “I tell Souraya (my aunt), in the west they do things very different! But here, this is not something we would usually understand.” I told him that the story had a happy ending, which it does – that my sister and I are now unquestionably family. “This is good,” he said, beaming. “This is very good.”

The aftermath of a car bomb outside the Cairo Police Directorate on January 24, which killed 5 and injured dozens. I was up early to go out and take pictures of Cairo street art, which, like all picture taking, was a little risky and better done at dawn, before the streets filled up. Even a kilometer away, the bomb shook the foundations of our hotel, and almost knocked me over in shock. Like all recent bomb attacks (almost all of which target police/military), an unknown, Sinai-based Islamist group claimed responsibility. A large number of Egyptians, maybe a majority, believe the Muslim Brotherhood is behind them, and uses fronts to stage the attacks, in order to preserve their image as a non-violent organization in the west. Is that true? Your guess is as good as mine.

Well-known activist and painter Mohamed Abla, who sat on the committee of 50 that wrote the new constitution. He was a 2011 revolutionary with lots of street cred tapped by the military-backed government to work on the constitution. It passed by an overwhelming majority, but less than 40% of Egyptians voted. Low turnout was attributed to both the Muslim Brotherhood boycott and the decision of young people who led the 2011 revolution not to participate. Abla agrees that young people are alienated from the process. He attributes this partly to the profound generational stasis that affects both of the country’s dominant poles of power, military and religious, both of which are led almost exclusively by men in their 60’s, 70’s and 80’s. He also blames the young, secular revolutionaries naïveté, and petulance about no longer being the in the international media spotlight. Abla is also absolutely convinced that the Muslim Brotherhood is behind all recent bomb attacks. As a teenager he was a member of a radical Islamic group responsible for waves of terror in the 70’s, 80’s and 90’s. “It was an open secret,” he says, “That they were directed by the Brotherhood.”

Story meeting at madamasr.com, an English-language daily news website financed by western NGO’s and run by 25 journalists who became disaffected with the ossified sycophancy of Egyptian state-run and private media (for whom they ran English language media) after the revolution. Of those 25, 90% are women under the age of 35. They are directly connected to the secular April 6 revolutionaries, dozens of whom are now in jail for protesting against military prompted laws that forbid protests of more than 10 people and allow for civilians to be tried in military courts, a long-standing, and much-resented feature of the Mubarak regime. Like most Egyptians, they supported the June 30, 2013 protests against Mohamed Morsi’s Muslim Brotherhood government, which seems universally recognized to have been a disaster, and applauded the military when it deposed Morsi and his government. Now they are depressed, and sure that the country has returned to military rule.

The Nile Corniche next to Tahrir Square. Normally these boats would be rented by tourists. Now they sit mostly empty. My hotel was Lonely Planet’s top rated mid-range hotel in downtown Cairo. Over two weeks I was its only guest. The Egyptair Airbus 330 I flew into Cairo on (from Heathrow) had about 30 people on it, 25 of whom were Egyptian. Of the five or so westerners on the plane, 3 were rumpled, corduroy-wearing American University professor types and two – sitting close to me – were a single pair of middle-age, female tourists. One of them was reading The Kite Runner. Before 2011 tourism represented about 11% of the Egyptian economy. Now it’s next to nothing.

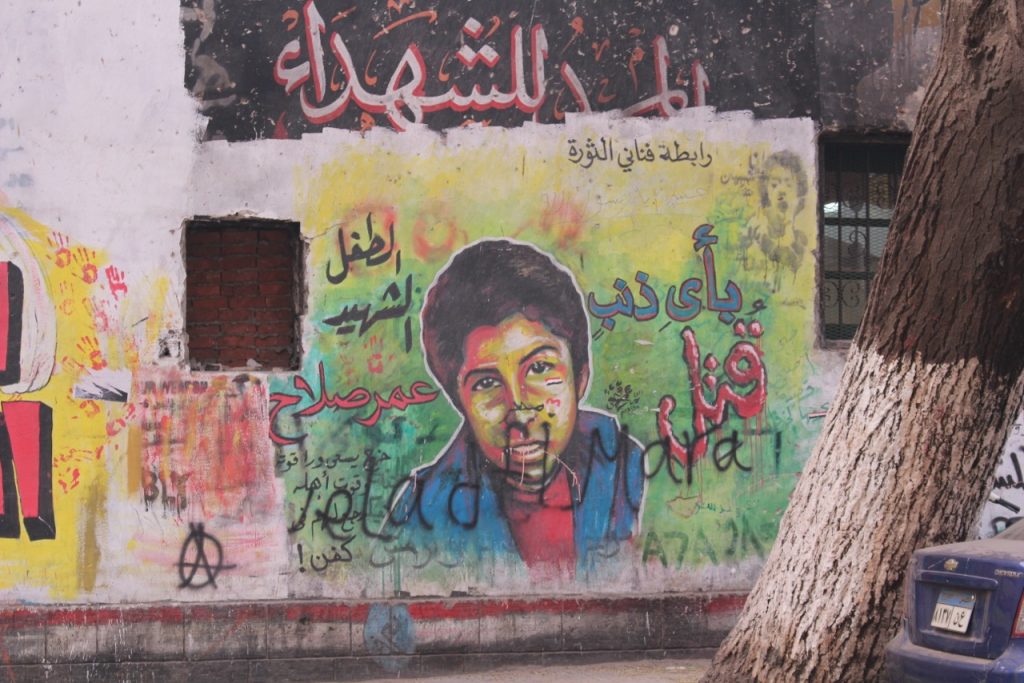

Cairo street art. The graffiti downtown is beautiful, and ubiquitous. Artists like Ganzeer have developed international reputations since the revolution, a kind of Egyptian revolutionary street-art chic. Much of it commemorates people who died, and much – like everything occurring there — remains contested. Pieces are regularly defaced or scraped away, and painted over and the repainted numerous times.

Me, with my Aunt Souraya and my first cousin Sally. This was the second time I’d met them in my life. On my second last day in Egypt, Souraya agreed to talk to me about my dad. She spoke for 75 minutes straight in Arabic, and when I tried to get her to pause, so my cousin could translate, she waved me off, saying, “Your father will understand, your father will understand.” All my relatives – men and women – are professionals, and Christian. All, in my generation and older, are also absolutely convinced that the military’s resumption of control was totally necessary in order to secure the country, and protect it from the real danger of Egypt becoming part of an expanding Islamic caliphate that they argue the US has made inevitable in Iraq and Libya, and may very well sweep through Egypt next. They are truly flabbergasted by the west’s current behaviour toward Egypt. “Do you want terrorists to take over the Middle East?” they demand. “Ask them,” they told me, speaking directly into my iphone mic. “Ask your people in America (sic). Is that what they want?”

Is your work connected to the…world outside world?

Laakkuluk: Hi gang!

Matthew: Hi Laakkuluk.

Amy: Hi Y’all.

Laakkuluk: Shall we get right at it? How, if at all, is your work connected to the world outside?

Matthew: Yes, How do international events impact you? How, if at all, is your work connected to the…world outside world…

Laakkuluk: I think we’re going to have to play with that typo.

Amy: kk. With regards to work being affected by the outside world I guess one lives in hope that others identify with our work, where ever they are from.

Matthew: Yes, making the universal specific.

Laakkuluk: Do you mean that you hope to have some universality in your work?

Amy: Yes, that is what I mean, Thanks for clarifying. Although language can be a barrier, but when I see theatre that is in another language I am still moved somehow. I don’t get to do that often. But…..

Amy: Universality has changed a lot since the internet. In Newfoundland, we used to be so isolated, cut off from the Outside world outside, but the world seems smaller now.

Laakkuluk left the room.

Laakkuluk entered the room.

Matthew: Speaking of cut off-

Amy: Are you having trouble Laakkuluk?

Laakkuluk: Sometimes i just have to look at the screen with the wrong squint and I get cut off. grrr

Amy: Careful of those squints. no dirty looks please.

Laakkuluk: I’ll try not blinking

Matthew: I want to come back to universality. I am interested in the first part of the question.

Matthew: How do International events impact you?

Amy: Like the Olympics? Patrick is going to skate very very soon. I have it on while I chat with you… I can’t help it.

Matthew: That will impact our chat.

Amy: I know. That is the international event right now. It’s sports but it’s what we got now.

Laakkuluk: My family lives in many different countries and so I have a personal connection w/ int’l events

Matthew: Really? Neat. I don’t think International events impact most artists.

Laakkuluk: My mother and I spoke with one of her aunts that lives in Faroe Islands yesterday.

Matthew: How do they impact you Laakkuluk?

Amy: Examples of events Laakkuluk?

Laakkuluk: she said she was cheering for Canadian teams because of our family

Amy: Sweet!

Laakkuluk: meanwhile I had to google who Patrick Chan was…Go Patrick!

Amy: heehee. I guess a lot of the entire world is watching now. Skating is very popular. It is an international language.

Laakkuluk: I find that because I don’t have television at home, I connect to the world differently.

Amy: Yes you would. Do you ever watch tv, or do you just use internet?

Laakkuluk: I watch tv at hotels! otherwise its internet for everything else

Amy: Do you like tv? Why do you not have one at home?

Laakkuluk: I don’t like advertising and commercials being broadcast into my house. I like good programes though, and artistic work and the news but it comes at the cost of watching advertising on the tv.

Amy: Yeah, I watch Netflix, choose what I want to watch a series at a time, and no advertising. Netflix is international, from the States!!

Matthew: I don’t think Netflix is the kind of International event they meant when they assigned this topic. I don’t think International events impact artists very often.

Amy: I have to say we do not get a lot of international representation on the stage here in Nfld.

Laakkuluk: why don’t you think so Matthew?

Matthew: 9-11 may be an exception…but generally artists are making new work about immediate situations. From what I recall of our discussions, we focus on our regions and issues there. Then we hope these are universal.

Amy: unless there is an international crosslink in our neighbourhoods.

Matthew: Or that there are universal qualities in the work.

Laakkuluk: Maybe because I studied political science in university, I don’t quite agree with you

Matthew: Oh, do tell.

Amy: We used to be an English colony not so long ago and I believe that influenced our collective theatre.

Laakkuluk: I think I am attracted to art (theatre and otherwise) that is making political statements and I tend to incorporate political thought in my performance as well. I think I’ve mentioned this before, but I have a piece on the “republic” of Hans Island the ridiculously small island that had disputed ownership between Canada and Denmark.

I guess that even though the piece addresses international dispute, I look at the universality of ice and oneness surrounding the island, as the self-declared President of the Republic of Hans Island!

Amy: Good for you.

Laakkuluk: being Greenlandic-Canadian Inuk myself, I love how silly it all is in the end. The island is only 1.2 km squared

Amy: Newfoundland’s being part of Canada is a very political international event. Many think it happened underhandedly.

Laakkuluk: yes – the internationalism involved in joining Confederation.

Amy: So we are affected by international events. Always, somehow politically.

Laakkuluk: for every single region and culture of Canada

Amy: Yes.

Laakkuluk: or being excluded by Confederation and fighting against colonialism to the present day.

Amy: We are all in this little world together affecting each other.

Matthew: Sure, international events impact us as artists and our work is connected in a universal way, but I am saying these events are seldom the reason for the work. Just a different way of viewing impact I guess. Hans Island is an exception. Are you the president?

Laakkuluk: yup that’s me.

Matthew: Madame President. Nice ring

Amy: I genuflect!

Laakkuluk: Merci. Arise dear Amy. We are all equals

Amy: No, Matthew, We are in the midst of royalty!

Matthew: I don’t know. Sounds like you could declare yourself co-president.

Amy: Ok Patrick’s biggest competition is skating now…. Who’s co-president? Laakkuluk: Like there should be a Greenlandic-Canadian and a Canadian-Greenlandic co-president? I like that

Amy: I’m in. How’s the pay?

Laakkuluk: there’s the problem of citizenship, which is easily solved, as a Canadian, you need to have had a Greenlandic lover, then you’re in.

Amy: Ok I’ll get right on that! Any excuse for a trip to Greenland. I’ve never been.

Laakkuluk: on it, she says…nice

Amy: Laakkuluk, you seem to travel a lot. do you?

Laakkuluk: I’ve been lucky to travel yes. Inuit performance has been good like that!

Amy: Mostly northern communities? Mostly in Canada? Or Where?

Laakkuluk: mostly northern hemisphere travel.

Amy: I’d say it is because you are good, not lucky.

Laakkuluk: northern communities, all over Canada, Scandihoovia, Britain, Germany

Amy: You are an international event.

Laakkuluk: Ha ha. Full of hybrid vigour as my father used to joke.

Amy: You do a lot of dance? Is there a lot of language in your art?

Laakkuluk: I think this seems to bring us back to Matthew’s observation that we make our regional, local perspectives understandable to the greater world.

Matthew: That’s what connects us to the world outside world.

Laakkuluk: Yes, there’s dance – that mask dance I was telling you about. And language for sure, makes me think of concentric circles, that turn of phrase

Amy: Our expression connects us to the outside world?

Laakkuluk: like we make an explosion of discovery within ourselves and then we push that discovery out to share with the world outside world as collaborative groups of artists.

Amy: Couldn’t have put it better myself! That explosion! That discovery. So exciting.

Matthew: Looks like Patrick Chan is about to skate.

Amy: he is…awwwwww

Matthew: A perfect example of an international event that will not impact our art.

Amy: but it will excite us.

Laakkuluk: okay. I’m starting to see what you mean, both of you!

Matthew: I’m only watching because the hockey is between periods.

Amy: he stumbled twice. My nerves!

Laakkuluk: The City of Iqaluit put up a pride flag for the duration of the games

Amy: Yeah we did in St. John’s too.

Laakkuluk: there’s been amazing and important discussion about it in Iqaluit and Nunavut.

Amy: about sexuality equity?

Laakkuluk: That’s an international event that likely affects our work!

Amy: Victoria?

Matthew: I don’t think there is a pride flag up at city hall or the BC leg. But we’ve been talking about it. How does it affect our work?

Amy: Gay rights you mean?

Laakkuluk: makes me feel like I need to be working more to discuss openness and diversity within the Nunavut community.

Matthew: Yes, Amy. Just curious about how it impacts our work.

Laakkuluk: there’s a sizeable group of people who are amazingly homophobic in Nunavut and another sizeable group that embrace diversity

Amy: openness and inclusivity, is always important in our work. But is it represented much is another question.

Laakkuluk: I think it’s important for performers like me to be helping with diversity and inclusivity

Amy: I do too Laakkuluk. Example is a good start. Lead by example. What we teach our children….by example.

Matthew: I feel like this particular issue impacts my life more than my work. I don’t make work on this topic, but I encourage diversity in my workplace. And encourage my child to be accepting.

Amy: But your life impacts your work. It’s in there somewhere.

Matthew: Yes, but it is hard to draw the connection in a direct way.

Amy: Patrick Chan got silver!

Matthew: Wow. You saw that before me.

Laakkuluk: that was fast!

Amy: Sorry. We are closer to Russia than you! 🙂

Laakkuluk: See – this is also a fun way of getting the news.

Matthew: For a moment there I had a secret Patrick Chan did not know.

Laakkuluk: I hear it from cool people like you

Amy: Anyway Matthew, you were saying…it is hard to make a connection to inclusivity and gay rights in your work?

Matthew: Yes. Not sure I can cover this in a chat, but…there is not a straight line (no pun intended) between this issue and my art making. There are other artists better poised to tell this story.

Amy: Yeah, I can see that. I identify. But we practice being open and inclusive in our lives

Laakkuluk: nor should it be a particularly straight line all the time.

Amy: though it may not be outwardly apparent, I believe our compassion shines through.

Laakkuluk: there we go!

Matthew: Thanks for the chat

Laakkuluk: Yes! Always a pleasure! Until the next time!

Amy: Soon!

not home

Photos by Jaclyn Turner

I’m presently traveling through Thailand for a quick holiday with my partner. I’m writing this from my phone at Railay beach in Krabi. Overlooking a sunset and crowds of mainly white westerners who, like me, have spent money to be not home. I’m typically conflicted about these trips. I want to see beyond my back yard and am happy tourism dollars stimulate otherwise struggling economies. But I can’t shake that we take these places for our leisure, make them ours and passively add them to our storybooks while neglecting the past, present and future of the people who’s homes we rent.

Flight delays handed us an overnight stay in Narita, Japan. Refusing to content ourselves to an airport hotel, we found a quiet hole in the wall restaurant swapping smiles and broken flowers with two patrons and the wait staff. Ca-Na-Da. That is our home.

They knowingly nod.

Yes, on est hiver. Many medals drape our athletes necks.

A few minutes pass before one remembers the sweetness of maple. “Syrup”, they proclaim, grinning the silliest of smiles.

Yes, our maple syrup is the best. I try to explain the tale of the great syrup heist of 2012. Pretty sure it was gibberish to them, but there was a quirky universality I had hoped they could relate to.

In the end, I know that this is what Canadians are to most of the world. Maple syrup and winter sports. Japan is sushi and sumo wrestlers. The U.S. is cowboys and hot dogs. France is baguettes and the Eiffel Tower. Thailand? Pad thai. National identities reduced to food, accessories, landscapes and sports.

In 2005, I co-founded Tableau D’Hôte Theatre, a company dedicated to presenting English plays from the Canadian cannon to Montréal audiences. The works of Walker, Thompson, Panych & co. had mainly been ignored by the larger houses and I was enamoured that such plays were written by Canadians, a concept that sorely lacked from my high school education.

9 years and many political battles later, I’m often embarrassed by our mandate. I stand proud of our work and the artists we create with, but it’s strange that somebody who doesn’t particularly like Canada, to dedicate time, money and health to indirectly trumpeting Canadiana.

Canada isn’t my land to love. It’s stolen land. We operate on unceded, unconquered and unsurrended native territories. Everything I’ve experienced and everything I am is a direct result of mass genocide and centuries of colonialism. Our governments unwillingness to acknowledge these truths and honour treaties fills me with rage and shame and I no longer hold any illusions to the myth of the peaceful,compassionate, progressive Canadian.

From our recent transphobic misgendered imprisonment of Avery Edison, to the police brutality and grosse infringements of civil liberties experienced during the G20 and Maple Spring protests, to the deadliest environmental project ever created, there’s little to go thumping our chests about as we trot around the globe.

Of course, all states have their their triumphs and travesties, and one joy of traveling may be the bliss of simply passing through. Little to cling on to other than your personal baggage and itinerary. But this rhythm is of great disservice to artists and storytellers when it ignores the here and the now and the then of the people around us.

Of course, all states have their their triumphs and travesties, and one joy of traveling may be the bliss of simply passing through. Little to cling on to other than your personal baggage and itinerary. But this rhythm is of great disservice to artists and storytellers when it ignores the here and the now and the then of the people around us.

Our hostel in Bangkok happened to be situated smack dab in the epicentre of the #ShutdownBangkok movement. Hordes of protesters have set up camp in the middle of one of the busiest commercial arteries. Despite my best efforts to understand the revolutionary movement before arriving, much of it remains lost on me.

It’s normal. Complex geopolitical realities aren’t exactly easy material to absorb. Understanding what rests beneath class breakdowns isn’t as simple as noticing extremely visible urban economic disparities. To begin to understand this, we need access to stories and storytellers. Access that is neither easy to find at home or abroad.

Abroad – most specifically when on holiday – we’re faced with extreme time constraints atop linguistic barriers. Whereas at home, our culture and stories are largely filtered through mass media conglomerates. Resistance begets resistance and without the tools to disseminate stories we remain complacent to our collective struggles.

And therein lay the power of the great equalizer that was promised to be the World Wide Web. Here, communities gather and intersect to share stories and fight back against economic injustice, against patriarchal forces, and against systemic and institutional white supremacy. Adequate translating and web accessibility permitting, both tales of a Thai uprising in Bangkok and the fight to save a student-run community garden at Carleton may be analysed, celebrated and spread far and near.

We are still relatively in the early stages of the game changer that is the Internet and much remains to be learned (and protected) if we are to reach an iota of its true potential.

As theatre artists, we need to challenge ourselves to see past imaginary invisible lines on maps and embrace the multitude of voices stepping up to change worlds. We must share these stories all while remaining mindful of cultural appropriation. The Internet is vital to making sense of complex matters and without it we’re left to cliché snapshots, cheesy tour books, and blankly staring at silent Just For Laughs gags in a room filled with people who each carry thousands of unheard stories. Without it, we’re left to Olympic medals and maple syrup.

#CdnCult Times; Volume 2, Edition 6

In my prompt to the Geographic Correspondents, I unintentionally included the language how does the “world outside world” impact your work? It has a ring to it though.

This Canadian world, despite spanning thousands of kilometers, has a remote consistency to it. Deceivingly immune from world events, it is possible to be an artist here who delves not too seriously into that kind of thing.

This edition contains articles that challenge that notion: Geographic Correspondents get into everything from Netflix to the Olympics, Neworld AD Marcus Youssef reflects on his Theatre Centre-sponsored trip to Egypt, and Mathieu Murphy-Perron writes from Thailand on his mobile phone.

Where are we going, with whom, and how are we connected to all of the people on this earth?

Michael Wheeler

Editor-in-Chief: #CdnCult Times