“An ocean is not an ocean”: design innovation in The Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst

The Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst by David van Belle and Eric Rose of Ghost River Theatre is the most technically challenging project we have ever worked on. We have had fantastic collaborative discussions on how dramaturgically vital visual manipulation is to the script and aesthetic of the show. David and Eric embed design elements within their writing and allow for experimentation during the long-term process development workshops. Unlike most theatre productions that bring design in during the last week of the rehearsal, we have been fortunate enough to have all the design elements present since the first day, working with director Eric Rose and the entire creative team. This ‘laboratory’ setting lets us explore lights, video and sound while the play is being created.

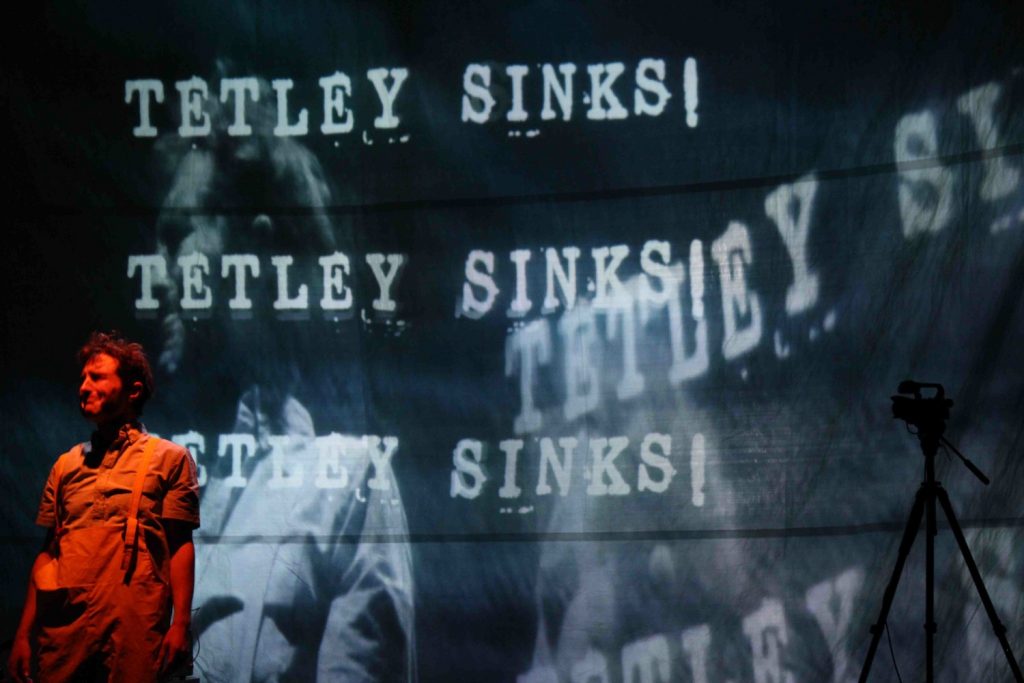

The imagery that is created live in The Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst is part of the mise en scène: a mix of video foley, live cinematography and prepared content. We are assisted onstage by two documentarians: actors who manipulate cameras and perform live video foley. The play not only requires a lot of video content that we need to create, but we are also using four HD camera feeds that are being manipulated in real time, processed and then sent to 8 different projectors. All of this is happening in one desktop PC running custom software that we have created in Touch Designer.

Touch Designer is a realtime-programming environment created by Toronto based software company Derivate. Similar to other visual programming software such as Max/MSP, Isadora or Quartz Composer, Touch Designer presents you with small nodes that you connect together to build a network of operations. For example ‘camera 1’ is connected to the ‘monochrome’ node (which converts the video to black and white) and is then passed onto the ‘output’ node which sends it to the projector. Unlike other software however, Touch Designer is highly optimized for video performance meaning that it is capable of delivering very high quality video at lightning fast speed. This system is cued via networked OSC messages from another computer we have running Qlab 3. This approach lets us trigger both sound and video from one computer and it also means that we didn’t have to build our own cue management system.

Matthew and the company worked on The Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst for three years, with many different video configurations including analog video mixers, Qlab, and Watchout. Having this time to experiment made us realize that we needed a more advanced media system to meet the needs of this production. Last year when Wlad joined us, we realized that it would take take a very powerful computer and software that didn’t exist. Matthew had just attended a Touch Designer workshop in Montreal and proposed that we try it out. We now have a very stable, fast, customized system that is allowing us to explore things we never thought possible. What’s amazing is that this would not have been possible five years ago. Or if it were, it would have cost twenty times what it costs today.

It feels good to be able to dream up an idea and then make it appear before your eyes, just as you imagined, a few moments later. The practical bridging of these new technologies and traditional components along with the development of new theoretical foundations will ultimately expose the semiotic impact of these aesthetic tools in how we tell stories. To accomplish this, we collaboratively developed rapid prototyping workshop environments for the exploration of scenography. These environments and process tools could enable the investigation of several versions of a group’s idea, visually realize them and efficiently document the results. The good ideas stay, the other ideas get discarded or tucked away for later use. This kind of experimental workshop format empowers collaborators to determine the best possible dramaturgy, generating a process that can ultimately unify show-control, highlight cross-departmental interactivity, and inspire creative exploration, while reducing programming bottlenecks and efficiently managing time.

The Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst by David van Belle and Eric Rose, premieres on February 27 at Alberta Theatre Projects, produced in association with Ghost River Theatre. Visit atplive.com to find out more.