What Happened to the Playhouse?

Was the Vancouver Playhouse Theatre Company doomed to fail?

Some might say that the organization was past its prime, and in a cycle of decline that can only be stopped in one of two ways: either by a revitalizing turn-around into a new growth phase, or by gracefully closing up shop and exiting.

Many signs pointed to decline. The organization closed reportedly carrying an accumulated deficit of $1 million. Richard Newirth, Managing Director of Cultural Services with the City of Vancouver says, “the biggest thing that I don’t think was really ever covered is that the Playhouse Theatre Company only posted surpluses 6 of 48 years of operation.”

This could be interpreted as mismanagement or a deep, structural problem with the organization.

The company was resident at the Vancouver Playhouse civic theatre and bound by a 50-year old agreement that prioritized the two other resident companies. Producing in the Vancouver Playhouse venue was expensive. According to documents provided by Max Reimer, Artistic Managing Director at the time of the closure, the Theatre Rental Grant awarded by the city paid for 85% of the expenses, leaving the company to pay the remainder – a number that ranges from $89,000 to $143,000 annually.

The company had also spent significant capital improvement funds on a temporary production centre, and was burdened by high rental rates while they waited for a new (city-owned) centre to be built.

Reimer refutes the life cycle and mismanagement arguments. He refutes “the structure never worked” argument too, for that matter. Of the deficit he says, “a large part [of that] was owed to the City itself on paper only – [and] would be excused officially by a later Council meeting.”

You’ll never meet a more optimistic person than Reimer. He is largely credited with turning around Theatre Aquarius in Hamilton. In his 12 years as Artistic Managing Director there, he brought in 9 consecutive budget surpluses, paid down the mortgage, and eliminated an accumulated deficit.

When Glynis Leyshon stepped down from the Playhouse, Dawn Brennan (General Manager of the Playhouse from 2001 – 2006) phoned Reimer up, “‘I think you’re the only guy who can do it,’” she said, “and then he came in and he couldn’t do it but he sure tried. It was too late by the time Max came in.”

I don’t think Reimer would agree.

To those who point to organizational life cycle models and say the Playhouse was in decline, Reimer asks, “on what terms?” Yes, according to CBAC analysis, subscription numbers went from 8000 to 5000 between 1996 and 2006, but sales had started an upward trend in 2009. Private donations continued to be at what Reimer calls “opera levels” up until closure. “And even down to the dying days, there’s a cheque for $200,000 which was never cashed.” And then there was the Wine Festival that brought in $400,000 to $800,000 per year. Net.

During his five years at the Playhouse, Reimer did, indeed, try. He renegotiated a change to the rental agreement with the City of Vancouver so that the Playhouse would not be charged beyond what the Theatre Rental Grant covered. More importantly, the Playhouse gained control of scheduling the venue. The Playhouse had previously negotiated with the two other resident companies: the Friends of Chamber Music and the Vancouver Recital Society. If by “negotiate” you mean planning – and paying – for the strike and re-install of sets to accommodate one-off concerts and events held by the other companies in the middle of the run of Playhouse productions.

Reimer also pursued operating funding at the municipal level from the City of Vancouver’s Cultural Services. For 48 years, the Playhouse’s Theatre Rental Grant had precluded them for applying. But Reimer pointed to a host of other organizations that receive Theatre Rental Grants or lease city-owned venues for $1/year and received operating support. He was successful and the Playhouse submitted a request in 2010.

(Reimer requested 2010 Operating support, but the $100,000 granted was called a “one time transition grant” in the recommendation letter from Cultural Services, and “emergency funds” in a later report to City Council.)

These are successes and, while not magically resolving the problems the organization faced, they could be seen as signs of recovery.

So what went wrong?

Operating funding is an important piece of the puzzle. And not because of the dollars. With the private sector support that Reimer describes, operating grants were only a portion of the Playhouse’s revenue stream. After all, the company had – arguably – been doing ok without any cash support from the City.

What’s more important is the mechanism by which the grants were awarded.

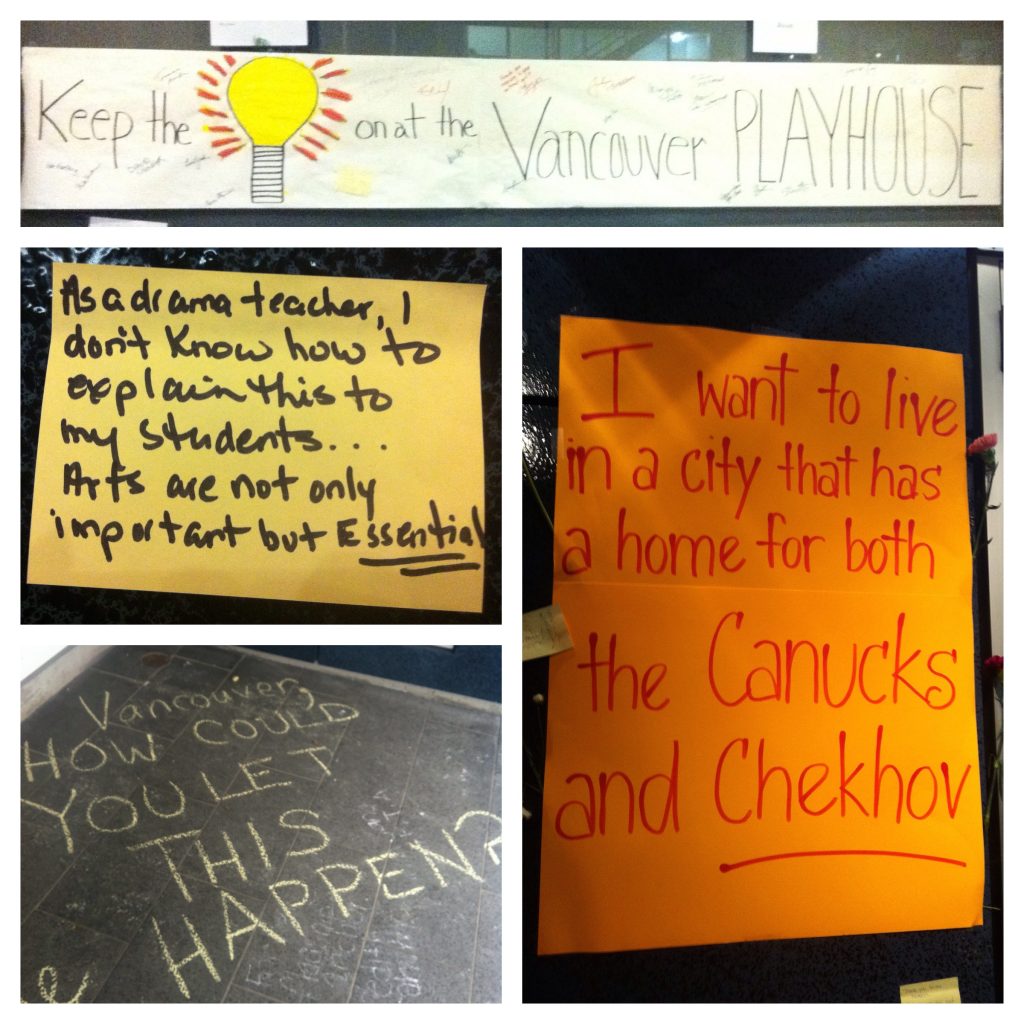

Somewhere along the line the Vancouver Playhouse lost the goodwill of the community, locally, in BC, and with colleagues across Canada. Peer assessment at the funding council level is one way to measure support from the theatre community. Everyone’s an expert over drinks at the bar, but when those comments reach the operating committee table, they have an effect – and in this case it was in dollars. Thousands of dollars.

In 2004, the Canada Council for the Arts reduced the Playhouse’s operating grant, according to Reimer, in response to jury comments that the organization was overfunded for its level of activity. In 2011, the BC Arts Council operating grants assessment committee cut the Playhouse’s funding by 2/3.

2010/2011 was a time of great financial instability for BC’s arts and culture. Gaming funding was denied to hundreds of arts organizations (and other social services) who had come to rely on it as core funding. The BC Arts Council’s budget was slashed 44%. In their Annual Report, the Council states they “decided against across the board cuts and developed a plan that would ensure a more merit-based approach.” The Playhouse’s operating grant was cut from $220,125 to $35,000 as listed in the above-mentioned Annual Report, likely because the Playhouse shut its doors before the grant could be paid in full.

The Playhouse again applied for municipal operating support in 2011 from the City of Vancouver. The request was denied, despite Committee members commending

“…the Artistic Managing Director for his role in revitalizing the board of directors and noted the significant achievement of exceeding box office targets in the 2009/2010 season. The Committee further commended the Artistic Managing Director for spearheading the transition for the company’s residency status over the past year and for developing and implementing meaningful new community collaborations and partnerships within the local theatre ecology.” (SOURCE)

Quoting from the 2011 Operating Grants recommendation letter received by the Playhouse:

“it was the consensus position of the Assessment Committee that the City of Vancouver would be exposed to undue financial risk and Committee members would not be seen to be undertaking their due diligence if they recommended a cash grant of any kind to the organization until the board of directors demonstrated that the society’s financial situation had stabilized or until they implemented appropriate restructuring plans.”

But that can’t be the whole story, because roughly $650,000 of the $1 million deficit was monies owed to the city, a debt that would have been forgiven at a later council meeting. Surely the committee knew that.

Of the committee’s decision, Newirth says “There was some debate about what role they were playing in the theatre community, [and], as the Arts Club grew, could the city support two very large professional theatre companies?” He goes on to say, “The clarity of the niche that they were filling was getting blurred.”

We only know about the $100,000 awarded in 2010 and the later City bailout (worth close to $1 million) because in camera city council documents were leaked to the Vancouver Sun. The news surfacing in this way supported public perception that the Playhouse was disconnected from the community and operated by its own rules.

I think the community had lost faith in the Playhouse.

Not everyone. But enough people talked about uninspired art, or unshared resources, and what is the role of a regional theatre anyway?

And this is where the Production Centre comes in. Looking back, Brennan says she would have walked away. “I really believed that we needed the Production Centre, that it was key to our identity, and the quality of our work.”

There have been many Playhouse production centres. The largest contained scene and costume shops, admin offices, rehearsal rooms and other production space. You would be hard pressed to find a theatre company in Vancouver that didn’t, at some point, benefit from cheap or free rehearsal space, shop access, prop or costume rental, technical equipment, or staff resources. The shop parties were legendary.

Brennan’s analysis now is that the cost of maintaining a production centre was out of sync with the volume of work produced by the Playhouse. “You can’t support what was an enormous Production Centre, for five shows a year, it makes no sense.” (Reimer takes issue with this, too, saying the Playhouse always produced a bare minimum of six and a maximum of 11 shows per season.)

But space isn’t just about the current programming, be it 5 shows or more. It’s also about what you could be doing, what you want to be doing. Until negotiating control of the venue, Reimer states the Playhouse “couldn’t hold auditions, host play readings, or add shows at the run” (SOURCE)

So why not just walk away? I can see that a venue – and all the ancillary programming you can put in it – and the production centre could be offered as direct benefits to the community. It’s the difference between arriving at the park empty handed or with a soccer ball. It’s easier to make friends if you have something to play with.

Of course the Playhouse held so tightly to the Production Centre – to the image of itself as serving the community – as a defense against the bar-room experts, those who would say it had outlived its purpose.

Perhaps the Playhouse had slowly drifted away from the ethos of Vancouver’s theatre community. Most of the companies in the city are artist-driven, many still headed by founding artistic directors. The Arts Club Theatre Company (the second of three large-scale theatres in Vancouver, the third being Bard on the Beach – both of which have control over their venues) was founded and is still run by Bill Millerd. Founded only one year earlier, the Playhouse had a succession of 13 artistic directors, the longest term being 11 years, most averaging four. It’s as if the organization grew up in foster care.

After the closure of the Playhouse, Vancouver City Manager asked Cultural Services staff to develop a policy for aiding organizations in crisis. Richard Newirth came back with “we don’t let them go into crisis. And that’s the big lesson that we’ve learned is that we need to be concerned about the financial health of our organizations regardless of how we’re supporting them.” It’s unclear how much the city knew of the Playhouse’s financial position in the years leading up to the company’s distress.

Vancouver’s 2013 Cultural Plan prioritizes developing “resilience” in the city’s organizations by “provid[ing] adaptable sustainable support programs.” Initiatives include capacity building and creating mechanisms for “sustainability planning,” among others.

Closing the Vancouver Playhouse Theatre Company was, Newirth says, a “wake-up call.” Vancouver had lost theatre companies before, but never one so big. The Playhouse employed around 200 contractors and about 15 administrative year-round staff. Many of those jobs are gone now. And some of the people who filled them have moved on, too. That’s what happens when businesses fail.

We are just scratching the surface of a complex scenario. There are more facts to be stated and – because we are artists – more stories to be told. To say the organization was doomed discounts the hard work of those who laboured to make it viable. The Playhouse had found its own delicate way of working. Maybe, in his efforts to improve the company’s rental deal with the City, Reimer disturbed the balance too much and it all came tumbling down.

Why didn’t the funders – no – the community value the changes Reimer was making? Was he pushing too hard, too fast? By shutting the Playhouse out of operating funding at the municipal level and hamstringing it at the BC Arts Council, the peer assessment committee members were, essentially, cutting ties with the organization, and saying “fend for yourself.” Maybe word of the renewed efforts to engage with the local community weren’t spreading fast enough. Maybe Reimer wasn’t managing to present a compelling argument in his grant prose. Maybe the Playhouse productions really were that terrible.

A friend of mine says, “every artist has the right to make bad art.” It’s practically a prerequisite. One could argue that permission to fail is a precondition of excellence. Unless you happen to be a regional theatre. Then, it would appear, it is a symptom of infirmity and you’d best be put out of your misery.