A Buck and a Half*

It’s that time of year when Indigenous performers become extremely popular for a day or two. True, “National Aboriginal Day” has become an entire month, but not many people have taken note of that. It’s the 21st that really gets congested for artists, with offers of underpaid work all over hell’s back forty. Annually, my art and life partner Andy Moro wisely ponders, “Why is it we’re asked to hustle every day this year, and never just get to enjoy it? Not the stupid fake holiday, but to celebrate the solstice.” The great light. Invariably, we find ourselves shuffling off to this or that venue, as our own PMs, wrangling a car rental, various props or set pieces and a performer or three.

This year is different. This year is Canada’s 150th birthday! Let them eat cake! Slather it with authentic maple syrup! Slap it with a beaver tail! BIRTHDAAAAAY!

This is not the first or last time Indigenous people will be asked along to celebrate something that lives in a very different place for many of us.

The commemorative events for the squabbling that happened in 1812-13 are fresh in the trenches. There was special funding and heaps of strange gatherings with union jacks and dudes in red coats. That year, I was serving as AD of ‘Canada’s’ oldest professional Indigenous theatre company, Native Earth Performing Arts. In our season brochure, I penned a message to accompany the aptly named “Treason Season.” It was a way to inform our beloved artists and allies that we would not be partaking in any commemorations, and would be opting out of accessing the earmarked funding. This, in spite of NEPA’s considerable financial struggles at the time. Some colleagues took offense and had words with me. These people had applied for and accepted the funding, and did not want to be judged for having done so.

The commemorative events for the squabbling that happened in 1812-13 are fresh in the trenches. There was special funding and heaps of strange gatherings with union jacks and dudes in red coats. That year, I was serving as AD of ‘Canada’s’ oldest professional Indigenous theatre company, Native Earth Performing Arts. In our season brochure, I penned a message to accompany the aptly named “Treason Season.” It was a way to inform our beloved artists and allies that we would not be partaking in any commemorations, and would be opting out of accessing the earmarked funding. This, in spite of NEPA’s considerable financial struggles at the time. Some colleagues took offense and had words with me. These people had applied for and accepted the funding, and did not want to be judged for having done so.

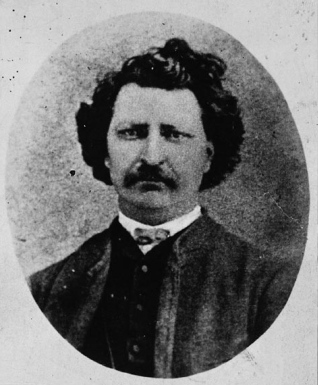

At the heart of it is the reality that wars like the one of 1812 are much feted. Meanwhile, major homeland conflicts like the Métis resistance remain in the history books as ‘Rebellions’. This means an innovator like Louis Riel – who established a diverse provisional government at 25 – was murdered by the crown, and his so-called “crimes” are yet to be pardoned. A simple walk through Winnipeg makes it evident that ‘Canada’ will use Riel as a poster boy, but they still will not give him his due by granting him a pardon or offering an apology for his slaughter at age 41.

Meanwhile, in 2017, the Canadian Opera Company are partnered with the National Arts Centre on an opera called Riel, written by a deceased white man, directed by a vibrant white man who many identify as an ally, with the title role enacted by a white man. This production has several politicized, powerful Indigenous performers in its ensemble. So… what to make of that? I send love to the actors on the inside and hope the experience isn’t painful to them. I hope also that the theatrical industry is shifting so that great performers don’t feel they have to take such work. I hope more of us work to create opportunities that privilege Indigenous agency.

Photo by Michael Cooper

As the COC/NAC Riel runs in Ottawa, VideoCabaret will be offering up their Confederation series in Toronto, starring Métis actor Michaela Washburn as Riel. As she writes on Facebook, “Louis Riel. A role of a lifetime! I have the abundant blessing of playing this fella from a young boy, plucked away to go to seminary school in Montreal, through to his last rites.” Somewhere inside me, I believe this is good medicine, striking a much-needed balance in a world where shit goes wrong every day. Washburn has always spoken her politics through doing the work, and she is in the position now where it is a benefit to many. I am reminded there are many ways to assert an Indigenous voice.

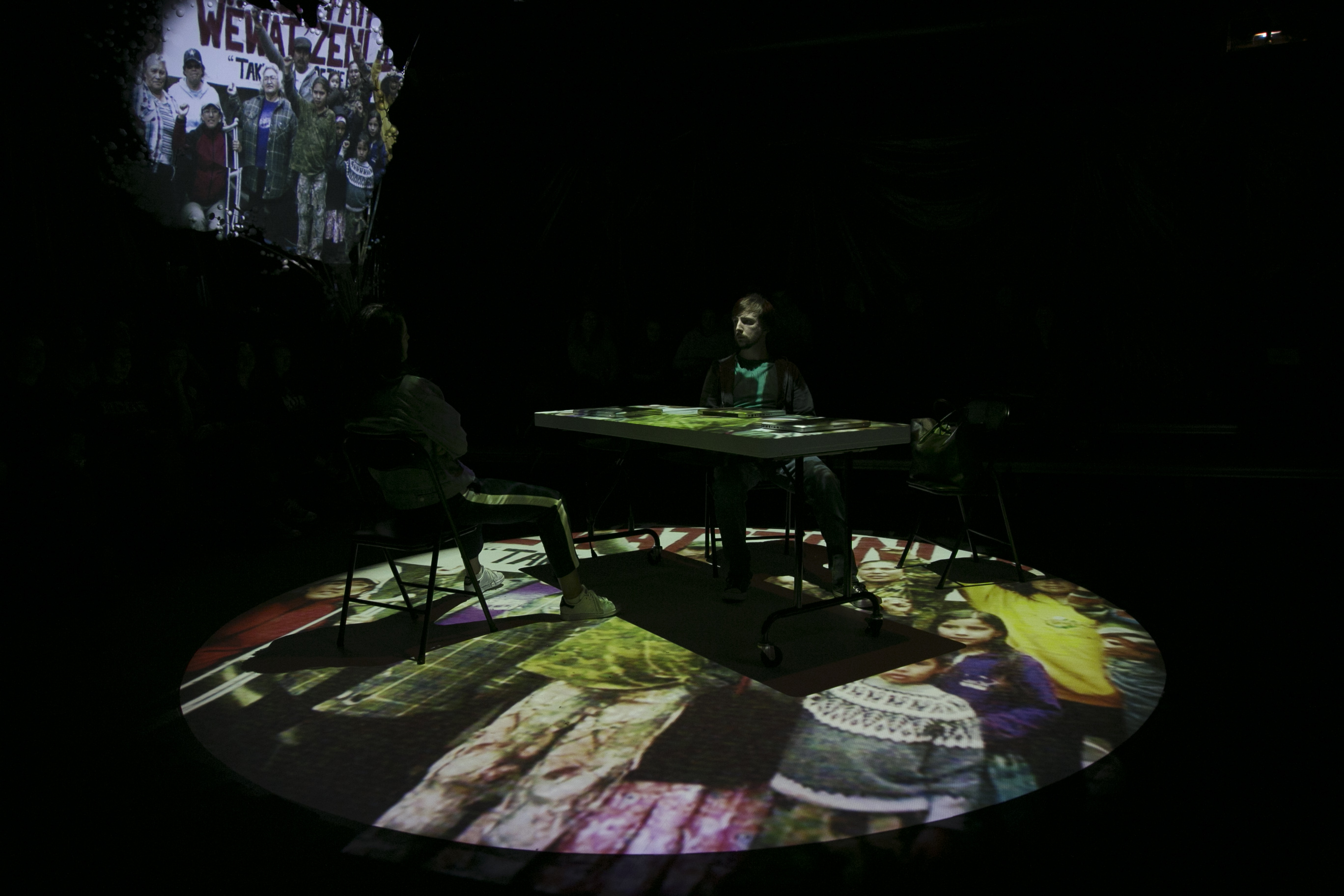

One arts leader who teaches me much, who is reclaiming not only her mother tongue but has also been at the forefront of Indigenous arts sovereignty throughout her career, is Santee Smith. Beginning in 2012 and running through to today, the magnificent Santee and her Kaha:wi Dance Theatre have created and performed The Honouring. Andy Moro is the creator of the fantastically striking video score that holds this work in time and space in any venue where it performs. He knew, at the time of creation, that this poetic piece would stand out from the bill it fit. At the time, I did not understand. Even when I saw it, I resisted.

The Honouring celebrates the way in which Haudenosaunee peoples have asserted their sovereignty by forging alliances that would best serve their rich culture. Colonization is inevitable. There was wisdom enough to see that within the Haudenosaunee communities, and they aligned with the British in order to land at what was hoped to be the best possible outcome for their families. The abundance of talented Haudenosaunee artists today is proof that this strategy was effective.

Santee is an activist who effects change through speaking out in her work, supported by Kaha:wi’s primarily Indigenous team, and dancing alongside several Indigenous performers. The Honouring continues to run today, as recently as May 2017. I am reminded that when a work is created and enacted by Indigenous peoples, even if colonizers consider it palatable, it may very well be a work that transcends settler anniversaries, reaching beyond the quota of the moment to be a greater celebration.

I write this, not to express my disdain for the 150 parties, a marker which has already been trumpeted. I write it to give thanks to those of you who live your truth differently than I do. I continue to learn through you. The gift of “National Aboriginal Day” might be that it gives us all that moment to consider what we can do to celebrate our voices, in our own ways. On the day that brings the longest sunshine, may you have a moment to turn your face upwards and take a breath of light.

*Beagan co-directs ARTICLE 11, who bring a new work A Buck and A Half to Theatre SKAM’s SKAMpede this July, in Victoria, British Columbia. Yes, that is an actual place name on unceded Indigenous soil.