Edmonton is a wild place to make theatre. There isn’t a lot of money – though perhaps more than in some other places. There are a lot of actors trained up really, really well and not enough jobs for them and the ones that came before them. Harder still, audiences are hard to come by, particularly in the dead of winter. It sounds like a cliche but no one wants to put on 15 layers of clothes and a parka to go see a brand new company giving something new a shot, let alone the same old-same old at the austere, concrete regional theatre.

But wildness isn’t all bad. And it’s good to get the complaining out the way first. Wildness here in Edmonton means a true passion for experimentation, a deep commitment to DIY aesthetics and methods of creation. Edmonton artists are often on the forefront of national recognition for contribution to innovation. And much of this finds its history in the founding moments of the Edmonton International Fringe Festival.

Founded in 1982 by Chinook Theatre Founding Artistic Director Brian Paisley, the first Fringe Festival was inspired by the Edinburgh Fringe. That first festival saw 200 performances in five venues. Flash forward to 2014 and the Fringe welcomes nearly 600,000 guests, nearly 150 individual shows, and nearly $1,000,000 in ticket sales. The Edmonton Fringe is now arguably the second largest fringe festival in the world after Edinburgh.

Through this rather illustrious history the Fringe, as it is affectionately known, continues to hold true to the values outlined by the Canadian Association of Fringe Festivals (CAFF): participation is determined by a non-juried process; participants receive 100% of their ticket sales (save for a $2.50 add on per ticket); the Fringe has no authority over content of the performance; and Fringes should provide accessible opportunities for audiences and artists to participate.[1]

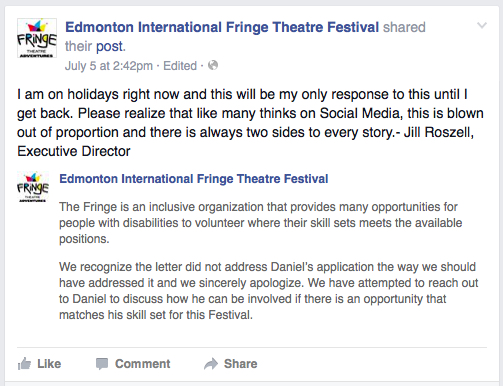

On July 5, 2015 it came to light the Fringe had altered its volunteer policy to exclude a number of persons with disabilities in favour of those whom, according to the Fringe, had more appropriate “skill sets”. The backlash was swift and forceful from both the theatre community and the disabled community. The Fringe reacted as swiftly and dug itself into a greater hole. Boycotts were called for and the media got involved. And this was all on a Sunday afternoon.

What happened to Daniel Hughes and a number of other volunteer applicants is offensive, at best, and possibly a human rights violation at worst. Worse still, the volunteer coordinator did not feel like she could communicate with Hughes directly and had to go through his aid worker, a further dehumanization.

Further disappointment came from the ongoing euphemistic use of the word ‘community’ in the rejection letter. That is not my community, and not the community of so many others. My community is a beautiful and inclusive one that promotes the participation and inclusion of all people. This situation is no different than rejecting a volunteer for being transgender or a person of colour or fat.

As a member of the theatre community and veteran fringe artist I was horrified and saddened by this new volunteer policy. One of my favourite parts of the festival has been walking up to the gates and seeing beautiful humans of all stripes sharing their love of a festival that has, since 1982, woven itself into the very fabric of our city and positioned Edmonton as a leader in the Canadian Theatre scene.

The beautiful collection of human faces reminds us that this is a festival for everyone and this all brings us back to the final tenant of the agreement that the Fringe makes with CAFF – and with us, their audience – “Fringes should provide accessible opportunities for audiences and artists to participate”.

Audiences don’t just come in the form of paid ticket holders; audiences aren’t just people who read an article in the newspaper; audiences aren’t only coming to see their favourite local “celebrity”. Audiences are those people too, of course, and we love them. But audiences are also the media, family and friends of artists, funders of all stripes, artists both past and present and, most importantly, volunteers.

A festival the size of the Edmonton International Fringe Festival does not run without a team of incredibly dedicated and passionate volunteers. And here’s a secret that many new fringe artists don’t know: volunteers are your biggest audience allies. They have big and passionate mouths that can shout to other volunteers, people in line ups, and people in the beer gardens. They chirp about shows they love and hate and are excited about. They see shows, 100s of shows, and their passion for shows is what leads them to volunteer. Without volunteers there is no festival, no real and joyful audience, and no money come in to the pockets of passionate (and often desperate) artists.

What remains to be seen is how this rather public, but necessary, shaming will affect ticket sales. It is impossible to predict what the shouts for boycotts will lead to, whether volunteers will walk away in solidarity or shame, whether artists will take up the cause, or if regular folk in Edmonton will have even heard the cries for inclusion and stay away.

[1] This information was obtained from The Edmonton International Fringe Festival.