Socially, politically, and ethically, celebrating diversity is part of the cultural zeitgeist of our time. It is simultaneously tied to our Canadian histories, greater global discourse, and the relevance/permanence of the artistic discipline of theatre in the 21st century.

This past Monday, the Jessie Richardson Awards took place and the development since last year was clear. The juries, the leadership, and the work that was being discussed have all undergone significant shifts following last year’s spark in discussion and advocacy. Yet, I would like to believe that we are not naive: there is still work to do.

The following is an acceptance speech that I delivered at the Jessie Richardson Awards on June 28th, 2016:

” Good evening. First, thank you to the jury for considering me — as someone who makes contemporary/experimental theatre, I greatly appreciate the recognition, both for my artistic practice and that of my peers which I feel, does not often have a place at these award ceremonies.

First, to all of my collaborators: thank you for your brilliance and criticality, I continue to be inspired by you. Over the last year, there has been a large and great discussion about diversity in the theatre.

In these cases, when we speak about diversity, most people deal in the materials of: [1] the politicized human body (casting protocol, having more POC on stage) and [2] content (whose stories we are telling). My hope is that we can move forward also dealing with [3] diversity in form. That our perceptions and our expectations of what theatre can look like, will not have to fit into the Western or European constructs that most of us learned in theatre school and/or the proven model that is selling tickets to the aging subscription audience.

I look forward to seeing and supporting more work that is theatre performance that does not rely on English, theatre that does not depend on the able-bodied performer, theatre that is not filtered through heterosexism, theatre that celebrates the vast cultural histories around us, and ultimately, theatre whose form challenges the very notions of what theatre can look and feel like. I believe in the necessity of carving out new spaces, rather than trying to fit the mould of white, male, mainstream theatre.

I personally don’t believe that the Jessies help in carving out this new space for the marginalized. In fact, I often perceive it as something in the way, something that preserves the existing hierarchy. Though beyond this one award ceremony, I must admit that I do believe in the people, the community, and most especially the next generation of artists. So to the strongly voiced and passionate collective who came together to change the Jessies and by proxy, the theatre community: thank you. Let us transform the theatre.”

In general: yes, we should rethink the structure and makeup of artistic leadership, yes to more open-minded casting decisions, and yes to creating avenues for sharing the narratives, experiences, and spaces of marginalized peoples. Though in a time when ‘diversity’ and ‘equity’ are buzzwords that also happen to look great on grant applications, I’d like to highlight the potential danger of white mainstream theatre form masquerading as diverse theatre.

Even if we see more POC telling their stories on stage, if the materials and forms are still of the Western/European hegemony, then we’re stuck with mere substitution and assimilation. Worse still, the very apparatus of the theatre becomes/stays invisible and we condition ourselves to believe that theatre form is synonymous with act structure, always serving a narrative/story/script, dependant on a hierarchy on the creative team, conflict that is predominantly navigated via text, etc.

And this is not to ask that we essentialize marginalized identities and practices, but instead, that we encourage diversity in the theatre as the conduit that disrupts and transforms our fundamental modes of operation.

So what does that look like?

I think it starts with challenging certain assumptions we may have about how theatre ‘works’; if we remove certain notions about what is necessary in the theatre, we can allow other artistic disciplines/apparatuses to find space in the theatre. Perhaps a theatre without conflict, without actors, without the letter ‘e’, without a director — the list goes on. I have no idea what it looks like, but it’s more exciting than the status quo. How will we know when it’s working? I’d like to believe that there will be more fighting about whether or not the work can even be legitimized as a piece of theatre.

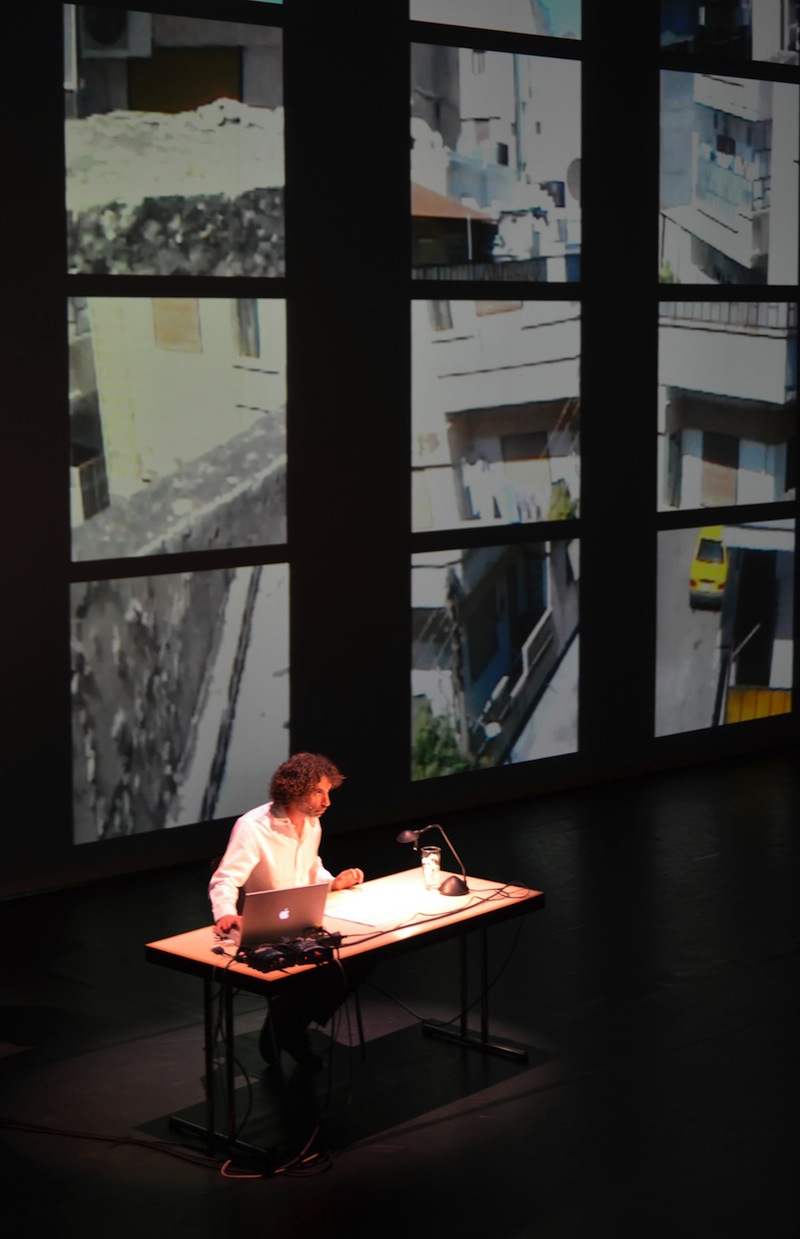

In 2012, I wrestled with the non-theatricality of Rabih Mroué’s Pixelated Revolution (1) at the PuSh International Performing Arts Festival. I couldn’t parse my feelings about his work as a piece of theatre, when all I could perceive was the presentation of a paper with some video support.

It took a long conversation with a friend, before I was hit by the cultural significance of subversive lecture-style theatre; creating a space of covert transgression that could be perceived as problematic by other methods. It was something I rarely think of in the privileged safety and ‘freedom’ of the West. The piece stuck with me for a long time.

The landscape is changing. When we speak about systemic barriers related to diversity, we need to consider the very form of theatre, otherwise, we’re missing the full range of what theatre can be.

I personally hope for the values of destruction and transformation in art: performance that is not simply made through synthesis or mimesis, but deep reformation that comes out of having cut away the foundations we were previously standing on top of.

(1) The Pixelated Revolution is part performance, part non-traditional lecture, examining the use of camera phones in capturing and disseminating first-hand experiences of the Syrian revolution, while exploring the role of social media in sharing and proliferating those images from the front line. http://pushfestival.ca/shows/pixelated-revolution/