You are watching a circus performance. The artists, for whatever reason, have a noticeable number of technical errors. The overall show remains cohesive, technical and artistic mastery are consistently displayed. Are you impressed by their ability to re-center and continue with the show? Or do you feel betrayed as a member of the audience, that you were witness to failed attempts? Participants in the Concordia Field Seminar were passionately divided after seeing Compagnie XY’s premiere during the 2017 Montréal Complètement Cirque festival.

These artists have trained hard to achieve enough skills to mediate the level of risk. Ideally, the skills and risk are balanced: not too much risk if your skills aren’t very advanced. At each step, the level of challenge should increase to a place where the artist, using their mental and physical focus, can achieve the harder movements. This is what creativity researcher Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi describes as the experience of flow, an “ordering of the consciousness” because all resources (mental, physical, emotional) are being put towards the accomplishment of one task. When circus artists undertake exceptional tasks with focus and confidence, it permits the audience to enjoy the show because we see that the risk is mediated with expertise.

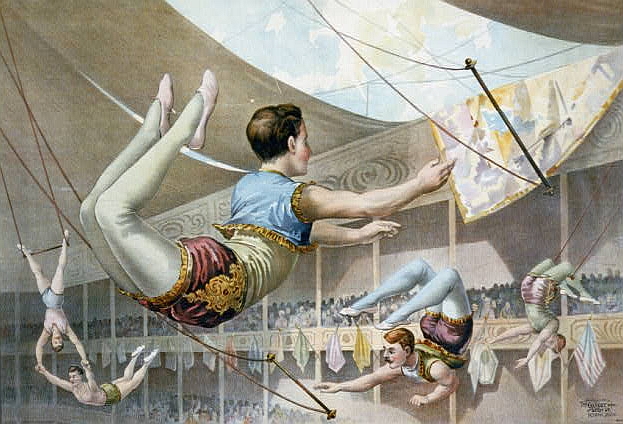

Imagine the traditional circus, where the whole audience holds their breath watching a tightrope walker prepare for their most difficult trick. Some performers include enacted mistakes at these moments, pretending to fall or slip (Hurley, 2016). Yes, it gives the audience a thrill because they believe they almost witnessed a grave accident. But it is also part of the writing, a reminder that what the acrobat is doing is so UNBELIEVABLY hard they have practiced failing nearly as much as they have practiced succeeding. Even with this risk, the acrobats have layered on musicality, choreography, and stage presence. Yet another layer, that they may be injured, tired, morning sick, jetlagged, food poisoned, or fighting with their partner, yet they are in the moment, fully focused in order to both provide performance and avoid trauma to themselves or the audience.

The dramaturgy of contemporary circus has shifted away from an enthrallment with risk, however, and explicit virtuosity is less valued. The contemporary audience, it seems, prefers to focus on the art rather than the risk, even though risk remains ever-present.

In Cirque Global Charles Batson writes about the human factor of the 7 fingers: seeing someone you ‘know’ on stage increases the “wow factor” (Batson, 2016). But he doesn’t address what happens when you see them fail. Are you more empathetic? Or do you feel betrayed because they didn’t deliver on their confidence? Angry because they made you afraid?

Watching my friends both succeed and fail, all those emotions jostle for their place. In Batson’s piece, as in most of Cirque Global, risk and injury have been erased from the discourse around contemporary circus. And yet, Francisco Cruz (Assistant to all Directors at the 7 Fingers) mentioned how in one touring year of Traces there were between 15-20 replacements due to injury. The failures may be hidden behind artistry, but they are never far away.

Have you seen someone fall out of the air, and not get up?

I have. Unfortunately more than once. For the trapeze flyer, he was tired. It was the last trick. He missed. He landed in the net, got up, repeated the movement. The show must go on, right? “We can get this,” I can almost hear him thinking, “we’ve done it so many times.” The second time he also falls short. When he hits the net, his body bounces like a ragdoll and he does not get back up. The show stops, the stretcher is flown in from its hiding place at the top of the tent, pre-set and ever-ready. I know he survived, but not much more.

We attend the show to see acrobats defy death, not succumb to it. I left the show angry because I don’t know if he pursued the trick for his own ego or because he needed to ensure he would not be replaced by the company.

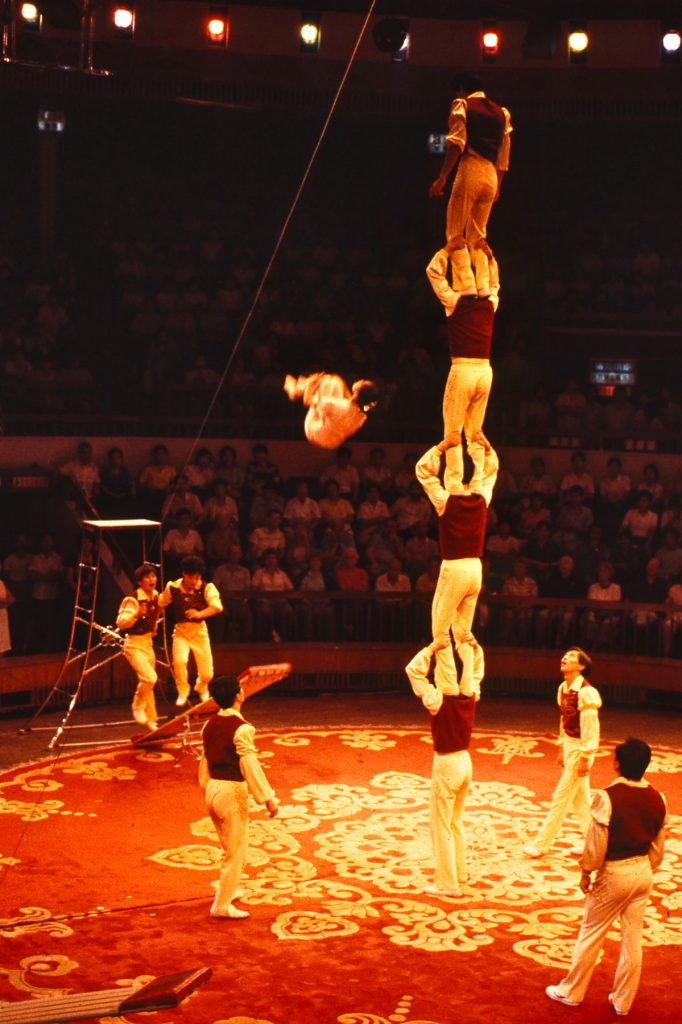

In counterpoint, I saw a beautiful moment in Il n’est pas encore minuit. One of the flyers didn’t nail the landing as she was pitched up to stand on a two-man-high column. As she folded out of the missed trick, I saw: The two-high bases were prepared, they were not injured when the trick didn’t work. The people who caught her before she hit the ground were ready. They leaned in towards her, maybe asking “try again?” She shook her head ‘no,’ and the show moved on.

She reclaimed agency on stage, deciding that her own safety and the safety of her partners was more important than proving she could do one movement for one audience at one particular moment. Even Olympians don’t always bring their best performance to the moment of competition.

I wish that the injured flyer had felt empowered to be an agent of his performance. I wish he had realized he might be too tired to achieve the trick. I wish I had seen him move on, instead of seeing him be lifted out on a stretcher, perhaps to never perform again.

Circus has evolved and audiences have evolved, and we want to see what else circus can express beyond the spectacular and act-based dramaturgy. And so, theatre directors, choreographers, producers, event organizers say to the circus artist integrated into their production: why can’t you just stay up there for 30 minutes, or hold that position longer? By the way, we changed your equipment so it matches our aesthetic, it is heavier, but we expect you to do the same tricks. Why can’t you wear this costume on that equipment? (All of these things have been said to peers in professional contracts, and sometimes resulting in injury or contract renegotiation).

These are all good questions. Questions which must be answered in collaboration with the circus artist. If the answer is ‘NO, that cannot happen AND provide the same quality circus,’ then the artist, who is risking their bodily integrity, must be part of the eventual solution.

Circus audiences, put at ease by the risk-assessed flow state demonstrated by performers, must bear in mind that the risk is real, ever-present. By accounting for that, they may experience the acute agency of a performer deciding when it is appropriate for a second attempt or when it is in the best interest of all for the show to simply go on. Experiencing this agency could offer another layer of enjoyment for the spectator.

Ultimately, the risk to a circus performer is much greater than the risk to a dancer or actor on stage. When the circus performer makes us feel confidence in their ability, confident enough to forget the risk, confident enough to focus our critique on their artistry, narrative, and performance choices, we must not forget that, at the foundation, it is because their circus technique is SO GOOD we are able to distance ourselves from the death-defying, spectacular narrative of the traditional circus.

Further Reading

Batson, C. (2016). Les 7 doigts de la main and their cirque: Origins, resistances, intimacies. In L. P. Leroux & C. R. Batson (Eds.), Cirque global: Quebec’s expanding circus boundaries (pp. 99–121). Montreal and Kingston: Mcgill-Queen’s University Press.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper and Row.

Hurley, E. (2016). The multiple bodies of Cirque du Soleil. In C. B. L.P Leroux (Ed.), Cirque global: Quebec’s expanding circus boundaries (pp. 122–139). Montreal and Kingston: Mcgill-Queen’s University Press.

Kliebard, H. (1975). Reappraisal: The Tyler rationale. In W. Pinar (Ed.), Curriculum theorizing: The reconceptualists (pp. 70–83). Berkeley, CA: McCutcheon.

Leroux, L. P. (2016). Introduction: Reinventing tradition, building a field: Quebec circus and its scholarship. In L. P. Leroux & C. R. Batson (Eds.), Cirque global: Quebec’s expanding circus boundaries (pp. 3–21). Montreal and Kingston: Mcgill-Queen’s University Press.