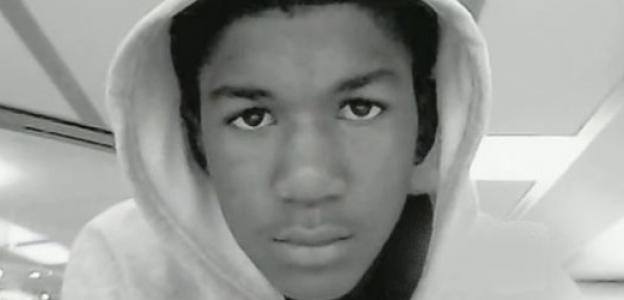

Black out. Dim lights slowly rise on the figure of a 17-year-old Black boy, as the remnants of Kendrick Lamar’s “King Kunta” fade into silence. He carries an iced tea and packet of Skittles. The boy steps into the center of the stage, intrigued by his surroundings. His demeanor is playful. His energy is bright.

“I didn’t know other people were gonna be here. Dope!” He sits in the house, studying his surroundings.

“Well…I must admit…that this is not all it’s cracked up to be. All that hootin’ and hollerin’ in church and heaven is just a black, awkwardly shaped room with a bunch of White people?”

The audience chuckles.

“Or am I in Hell?” He jokes. He is infamous – the unarmed Florida teen who was shot dead walking home from a 7/11 one evening by George Zimmerman. He is Trayvon Martin, and this past summer, through the portal of a black box theatre, I choose to bring him to life.

I am Makambe, a Zambian theatre artist who is currently based in Calgary. I am performing a ten-minute solo piece at the Summer Lab Intensive with One Yellow Rabbit. I play Trayvon.

I don his now iconic hoodie and baggy pants and bring this beautiful boy to life with a monologue that strongly resembles that of a stand up comedian’s. Trayvon learns that he is about to fully transition into the afterlife. He recounts bible stories, and remarks that he can’t wait to see his ancestors. As Trayvon, I make the audience laugh, and sigh. This monologue is sprinkled with truths of this boy’s life that I found in news articles – such as the sports he played, his favorite rappers, and his fond appreciation for Krispy Crème doughnuts. Trayvon has the audience in the pam of his hands, as he finds an instruction manual called “How to Lead Newly Released Souls on a Journey to the Ancestors.” He follows the instructions to lead his own soul, and the souls of those in the audience to the afterlife.

The piece ends with Trayvon reliving his last moments, as the final step towards fully passing on. In a fictionalized final phone call with his mother, he rolls his eyes as he mutters “Love you too,” and promises to be home shortly. Then, underscored by Kendrick Lamar’s unapologetic lyrics, we see Trayvon’s ill-fated walk home, during which he is followed and shot dead for no reason. The piece ends with his lifeless body center stage, his hoodie wet, and the lights of his ancestors circling around him.

I am touched by the comments of the audience, some of whom knew Trayvon’s story, and some who did not. Some who told me of their friends who died at the hands of police brutality, and others who remarked how easy it is to forget that the names we see in headlines like his belonged to actual human lives. My peers and mentors encourage me to expand the piece past it’s current ten minutes. “This topic couldn’t be more relevant right now.” I agree. I happen to have performed this short in the same week that social media is swirling with news of the deaths of Alton Sterling and Philando Castille, and the hashtag #blacklivesmatter continued to build even more momentum than it had before.

Weeks later, I am asked by a local Artistic Director how his company, for which I have great respect, can support my development of this project. He says the company would love to offer me time and rehearsal space to develop the piece further. Wow!

I immediately accept. I am humbled, energized, and already buzzing with ideas. The meeting ends. I grab my moleskin and just as I am about to put my pencil to paper, something hits me. It feels like confusion, tastes like fear, and makes me start to think about who I am.

I am African, Not African American. I am female, not male. I live in Calgary, not Florida. I trace my lineage to great chiefs and kings in my native Zambia rather than to those who unwillingly crossed the Atlantic on slave ships. Yes, I have experienced racism, but for the most part, my experience of stories like Trayvon’s, and all other reminders of the dangers of being Black in North America, has come from behind the shield of my computer screen.

I was raised in an upper middle class family with two highly educated and loving parents and a lot of privilege. One of those privileges is that although I have experienced racism, I have never felt my life threatened because of the colour of my skin. Another privilege is the fact that if ever I decided that living in North America wasn’t working for me, I have the easy option to move “home” to my country of birth and I would be happy to do so.

Telling Trayvon’s story comes with huge weight, because it is not just his. He represents generations – thousands of Black men and women who have been senselessly brutalized simply for the colour of their skin. He represents our present world in which men and women of colour have lost their lives for a failure to signal, or for reaching for a wallet at a traffic stop, for selling cigarettes, for simply existing. He represents the coming generation that is emerging into a world that continues to reminds us how far we haven’t come.

Because Trayvon’s story is laden with so many experiences, realities, and fears that I may never experience first hand, should I be the one to tell it? Or is this cultural appropriation? Am I somehow cashing in on the painful and complicated stories of my distant cousins?

Several weeks have now passed, and I haven’t written a single word. I am scheduled to begin to develop this piece with a director and dramaturg in just a few days, so after weeks of pondering in my own anxiety, I am forced to answer my own question.

Yes, I should tell this story. This story is mine. I have chosen to accept it as so.

Yes, my circumstances are different than Trayvon’s and many other black North Americans, but we do not all have to have the same life experiences understand one another’s struggles. No matter where we come from, or which privileges we may or may not have, we are all affected by the injustice that the Black Lives Matter movement addresses.

My great, great grandparents were not slaves on American plantations, but my ancestors were still oppressed and abused through the colonization of their home, the effects of which are still seen today. And it is that same racist system that thought it a worthwhile venture to force black bodies into slave ships. These truths, as well as those of so many other oppressed groups whom I have not mentioned in this article, are intricately connected, and have resulted in a world where inequality is rampant and tragedies like Trayvon’s (not just his murder, but the lack of justice following his death) continue to be a norm.

So yes, I am the one to tell this story… but I am not the only one on whom this responsibility falls. This is everyone’s story, because the fact that we live in a world with so much hate and inequality, that for some it is dangerous simply to exist – is everyone’s problem. This is the truth I continue to remind myself of, in order to feel empowered to create.

I look forward to the day that this play, and plays like it, can be presented with the qualifier, “This is how things used to be”, rather than “This is how things are.” But in order for us to get to that point, the stories must first be told. It is through these stories that lessons can finally be learned, and healing can begin, for everyone.