To save the world from what Avi Lewis describes as “capitalist planetary suicide”, theatre companies should become co-ops. Theatre is not charity. It is work. In its abstract form, of course it’s art, but in economic terms, it is the product of labour, valued by the communities who consume it, and produced by a class of (in my opinion) undervalued and exploited workers. Our labour generates an enormous amount of wealth within secondary and tertiary economies, and we don’t see a penny of that profit. What’s more, most of the workers who make art are shades of anti-capitalist at this point in history, so why are theatres captive of a business model that support a capitalist economy when other options exist?

As we all know from the moment we turn 18 and decide we’re going to open our own theatre company to produce that awesome Fringe play that will make us famous, every theatre in Canada is forced to choose between two economic models: for or not for profit. While the NFP model releases us from a mandate geared exclusively to the benefit of corporate shareholders, it comes with many strings attached, the most insidious being that we are trapped inside a constant cycle of having to prove that our work provides justifiable benefits to society. In a constant drive for increased donors, government funding and foundation grants, we have no choice but to market our work within the paradigm of Christian charity.

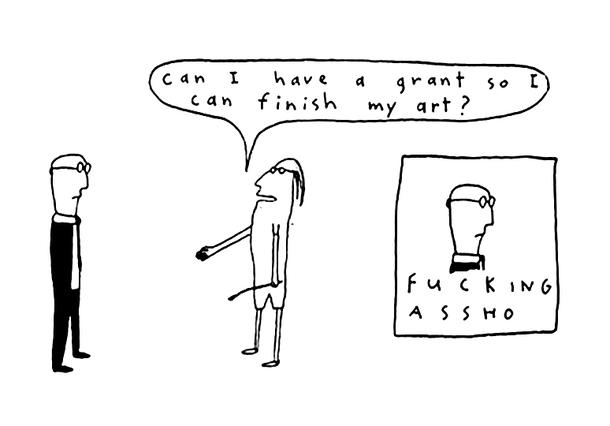

The work of fundraising detracts from, and contorts our art making. The unspoken deception at the heart of this, is that we’re successful as fundraisers not when we’ve demonstrated our worth to society, but when we’ve demonstrated our worth to wealthy patrons, who, in spite of being bewilderingly oblivious to it, are deeply complicit and dependent on the corporate capitalist paradigm that is generating the inequality that our plays decry.

We are earnest in our desires to change the hearts and minds of our neighbours through storytelling. I, in no way abuse that work when I say the tax break a private developer will get from donating to a large NFP Theatre will be used to evict low-income families far faster than our plays about those evicted street kids will create the kind of political will necessary to expropriate the developers. Moreover, the taxes that corporation doesn’t pay would otherwise be used to house low-income people (perhaps in housing co-ops!). This is the math that keeps charities humming along while the world burns ever faster.

Good news, fellow socialist thespians! Co-ops have existed as one of the most sustainable and socially responsible economic models since industrialization. Every business can become a member and/or worker co-op. Co-ops are owned by the people who benefit from them. Internal democracy is a core principal. Workers seize control over the product of their labour (Hi Marx!), and no one (not even the bank) turns a profit that goes into offshore accounts, third mansions or pipeline expansions.

Some artistic production companies have adopted this model in Canada, including visual art, radio and filmmaking co-ops. I believe theatres can too! I believe that the communities we genuinely want to support and influence can become members of these co-ops. As well, I think if we force our professional associations and unions to take on this task, we can convince the granters, beginning with Canada Council for the Arts, to give us grants along with NFP theatres. CRA would also have to acknowledge us, although in many ways the tax laws that apply to co-ops may be more appropriate for artists than the tax laws that govern charities.

It bears saying again: Theatre is not charity.

Another exciting lure is that the federal government invests in co-op startups, and co-operative banks are more than happy to give loans to other co-ops. They do so not because co-ops are charitable, but because they have proven their fiscal worth to society many times over hundreds of years. Co-ops are far better at withstanding recessions and stock collapses, and the wealth they generate benefits local economies and is quickly seen again by governments. It’s taxed. We call it: “The solidarity economy”.

My friend, the brilliant, anti-capitalist writer and activist, Dru Oja Jay, writes that “co-ops represent billions of dollars that have been effectively taken from profits for banks and handed to people, often some of the most disadvantaged.” He goes on to describe that they pay their workers a bit more, they use sustainable, ethically sourced materials and labour from other co-ops and they pay below market rent, subsidized by the funders. They invest what could otherwise be spent on fundraising in the product they create or the workers they support.

Once robust co-ops (banks, housing co-ops, agro/food co-ops… Basically every industry seems to have co-ops except Canadian theatres) start to turn profit, which they do remarkably quickly, they have the option to reinvest their surplus in other co-op enterprises that benefit society. I see theatres pitching themselves here in order to secure more startup capital directly from other industries. Which is what NFPs do, of course. They just call it charity. Some arts producing co-ops sell a second tier of membership to the people in neighbourhoods they work in. The entire community then becomes a partial owner, and is given a democratic voice in the operations of a theatre. How wondrous and beautiful is that dream?

Co-ops fundamentally threaten and disturb capitalist imperatives, where charity does not. Charity, at its best, treats the symptoms and victims of capitalism with unsustainable compassion. Due to the Christian origin of charity, which values handouts as a means to become closer to God and to demonstrate virtue, it must exist outside the economy in order to be exceptional.

To quote Dru again: “The main line of accountability in a lot of non-profits is from their upper-level staff and board to their funders. Decision making is formally conducted by the aforementioned leadership, but these folks have to keep funders’ priorities in mind all the time. Cooperative structures and business models, by contrast, tend to align the creation of value with the needs of members, and gives those members the power to make decisions. A worker co-op gives decision making power to the workers, and a housing co-op gives power to the people who pay the rent.”

For co-ops, social justice is intrinsic to the business model, not a justification for fundraising. The co-op is built on the value of the work itself. If we believe our work is inherently mutually beneficial to workers and people alike, then why not co-ops? If the communities we claim to serve are members of our co-op would we have to constantly prove that we are serving their needs or would their literal ownership of the company take care of that?

My last, and admittedly strategic, pitch for why theatres should be co-ops, is because it would bust the narrative that we are people who write stories about justice and give us a way to become that justice. The co-op movement mutually supports all kinds of social justice solidarity movements. These theatres would gain us immediate membership in national and global anti-capitalist movement building, simply by adopting a different, more sustainable business model. Artists would have opportunities to learn so much just by showing up. In short, this is how theatres can be part of the revolution.