The Same Old Story

Laurier was moved and promised, as politicians do, that if re-elected he would take the conservative BC Government under Richard McBride to court and get them to sign treaties with the native tribes of the province.

There were very few treaties in British Columbia between the native peoples and government then (which could be seen as similar to today), and the BC government opted to act unilaterally and ignore the process altogether. Disputes over native lands and immigration were the main conservative issues of the day. Sound familiar? Robert Borden ran on a campaign of “A White Canada” directed against Aboriginals and Chinese immigrants in British Columbia. This campaign delivered every single federal seat in BC to the Conservatives, and Borden defeated Wilfred Laurier’s federal Liberals in 1911.

At one time, Premiere McBride was seen as a possible replacement to Borden as the leader of the federal Conservatives. But McBride opted to stay provincial, and once Borden was in power McBride called in a favour for not running nationally; and thus the McKenna McBride Royal Commission was established to “solve” the Native Lands issue once and for all.

What resulted was relocation, reduction, and the removal of Native peoples from their already established reserve land base onto often less beneficial or greatly reduced lands. Under amendments to the Indian Act natives were restricted from leaving the reserve, from hiring their own lawyers, and from gathering in groups for religious or political purposes. They were also discouraged from competing directly with white farmers, and were forced to sell their farm produce on reserve only. It was at this time that the Residential School system began to ramp up… The deep legacy of these colonial policies are still felt today.

Fast-forward to the 2015 election cycle, which in my mind has the distinction of being the most racist campaign since Borden’s successful bid 104 years ago. In 2015, the economic policy debate goes hand-in-hand with the wedge politics and bald-faced racism at the federal level. How can a political party in this day and age deliberately target an already demonized minority of Canadians and be entrusted with our sanction to lead? What has happened to the Canada I grew up in? What happened to multi-cultural, pluralist Canada? Have we devolved so far? Maybe we haven’t changed at all.

Bob Zimmer, conservative MP running for re-election in Prince George- Peace River, said during an all candidates’ debate, “One of the drivers of missing and murdered aboriginal women is… the lack of a job. Ultimately when people have a job, they’re not in despair. They can stay on reserve, and that’s where we want them to be.” That’s where we want them to be? This guy is already an MP!? With this kind of ammunition, I did what any modern citizen does these days, I expressed my outrage on Facebook. I was determined to get people to vote and vote for change.

Across the country many First Nations people are coming out to vote in this election for the very first time. I am N’lakap’amux. We are an interior Salish tribe located in the Thompson-Nicola region and the Fraser Canyon of BC. And like most tribes in BC, we haven’t signed a treaty with the Government of Canada, so technically we are a sovereign people even though we are administered under the Department of Aboriginal and Northern Affairs. Many First Nations people refuse to vote, believing that any endorsement of any party is tantamount to supporting the enemy.

I got into a heated Facebook debate with a really nice guy (and well known Aboriginal artist) that I’ve known since childhood about the importance of voting in this election. In my over-zealous attempt to get him to vote, I ended up bullying him and alienating him further. My passion overrode my discretion. My argument was, “If you don’t vote, you can’t bitch.” You can’t complain about a government you did nothing to try to alter. His argument was that it doesn’t matter which party forms a government, it cannot represent him because by endorsing any party he would be endorsing the continual suppression of his peoples’ sovereignty. Conscientious objection.

I challenged him to research the work of the Allied Interior Tribes, a precursor to the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs. How they marched on the Victoria Legislature, Parliament Hill, and even Buckingham Palace to demand inclusion, recognition of their sovereignty, and a seat at the table. How our ancestors fought to gain the vote in 1960. Before that a First Nations person would have to give up his identity as an “Indian” to be “enfranchised” as a citizen of Canada. His point of view was only solidified. He would never vote. And I was simply “colonized” for voting.

The truth is, I really can’t blame him. I get it. I disagree, but I get it. Because what will actually change with a new government? Under the Liberal decades the same kind of suppression of aboriginal rights and sovereignty took place as the Conservatives. The first Trudeau tried to introduce the “White Paper” an attempt to abolish Aboriginal rights and title. Maybe under an NDP government we’d see some real change … but what are the chances of that? Only Albertans know for sure.

In 2015 Canada hasn’t evolved beyond the demonization of racial minorities for political gain. Bigots make up a large enough portion of our electorate that wedge politics can take hold. We still have a long long way to go with regards to Aboriginal issues. Under the Conservatives we’ve seen nothing but devolution. And the myth of the multi-cultural all-inclusive Canada fostered under the first Trudeau Government may very well be in its death throes. All I have to counter this offensive political climate is my vote. I voted for change. I sure hope we get it.

The Great Canadian Showdown and the Bloodletting of Canadian Artists

The emptiness — that hollow feeling of routine and boredom — that’s going to befall us after the votes are counted is already in the air. Regardless of this election’s outcome, Canada is headed straight for a kind of postcoital depression: Toppling over like a limp dick, no longer courting us for every moment of our attention, the Tom-Justin-and-Stephen show will transform from a bundle of exciting masculinity into an annoying mess. Slowly our ears will grow tired of day-to-day politics, and begin to close off to the quarrels on Parliament Hill.

I already fear that post-election moment when politics begin to re-retreat into the scenery of our lives instead of continuing to occupy the central role they’re currently playing. It’s deeply symptomatic of Canada’s political vulnerability that democracy and its processes only gain broad public significance when the immediate overthrow of someone like Stephen Harper is at stake.

And it is probably due to this inconsistent attitude towards politics in Canada that Canadian artists have so far failed to recognize their implicit politicization — that their bodies and minds function as political instruments — that can only be undone when artists begin to reclaim their democratic autonomy through a conscious politicization of their identities and their work.

As a result of our neglect to self-politicize — and to organize ourselves — a crucial election has now managed to pit our artistic agenda against our political conscience, forcing us to choose between our identities as artists and our responsibilities as citizens.

The Schizophrenic Artist

Arts and culture had no place or voice in this election, because something seemingly greater and more important was at stake. To continue waving the lonely flag of arts and culture, while Stephen Harper’s Conservatives suggested a bizarre, Gestapo-esque tip line to report “barbaric cultural practices”, seemed ridiculous. My needs and wishes began to feel foolish and cute: “Oh, you’d like to talk about the Status of the Artist Act? Well, fuck off! There are citizenship issues and a broken environment and an anti-terror act and traumatized Syrian refugees in need of your attention!”

In comparison to everything else that this election implied — and, above all, everything that it signified — art felt like a non-issue, like a distraction from that which really mattered. I began to feel ashamed of my needs and ideals as an artist. I decided I better stop worrying about what was going to happen to art in Canada, because man, that tip line! That citizenship act! That [fill in the blank]! In effect, I began feeling ashamed of those moments when I had cared about my life and future life as an artist in Canada: How selfish! How misguided of me! In a way, I unconsciously bought into the conservative Common Sense argument against art, allowing it to pit me against myself: “Pfff, art! Who the fuck cares? There are bigger things to worry about.”

But to deny oneself one’s needs is to confuse the body. It is to let depression seep in, to let paralysis wreak havoc. It is to tie one’s own hands.

The binary between our artist-selves and citizen-selves shouldn’t exist. In order to defy destructive arguments “against” art — those that question its immediate “value and “purpose” — our “two selves” and their associated responsibilities must live in unison: in constant conversation, our art and citizenship should coincide, be productive together, through collaboration. They mustn’t force each other into silence; they mustn’t outweigh each other, or ever make each other feel small and insignificant; instead they should strengthen and depend on each other. Any other relationship between the two is illness, is fear, is suicide.

The truth is that Canadian arts are Canadian democracy and vice versa: art is deeply linked to, and intertwined with, any issue that concerns the state of the nation. Early on during election season, on August 25, when lobbying for arts and culture wasn’t yet a petty act worthy of self-hatred, I wrote an open letter to the leaders of Canada’s four major political parties, outlining how and why art and culture are a crucial democratic constituent:

“Historically, the arts have functioned as a means … of engaging with, questioning, and criticizing the state of society. Consider, for example, the many works of Leonard Cohen or Margaret Atwood. Consider Michel Tremblay’s play Les Belles-soeurs, Sky Gilbert’s Drag Queens on Trial, Tomson Highway’s The Rez Sisters, Hannah Moscovitch’s This is War, Brad Fraser’s Unidentified Human Remains and the True Nature of Love — the list goes on. These works have been instrumental in the social, moral, and democratic education of Canadians, allowing their readers and audiences to employ their intellects and imaginations independently, to construct and negotiate possible versions of the world, to explore, ponder, and deliberate. “The kind of problem that literature raises,” is crucial, because, as Northrop Frye points out, it “is not the kind that you ever solve.” In other words, the arts comprise an essential component of Canadians’ intellectual and political self-determination.”

Stop the Drain

In order for the above to be true — in order for us to embody our democratic function — we must reconcile our artistic identities with our responsibilities as democratic citizens. We must disable our politicians’ “barbaric cultural practice” of pitting our artistic agenda against our democratic conscience, of playing us against ourselves. We must instead begin to regard our two halves as a whole, as indispensable entities of an organic organism. And to get there, we must ask ourselves some questions — NOW, not at the next election:

- What is our project? What does our political system demand from us — what kind of art and what kind of action? To what extent do art, action, and activism coincide? The question is not whether the tip line is “more important” than art, but rather in what relationship art stands to it. Our job as artists is to think about how we, specifically as artists, should be responding to such political ideas and events.

- Is there an “Us”? Does a “We” exist in the artistic community? If so, how and where? And if not, why? What would have to happen for us to become a “We”? Do we think a “We” is possible? Is it necessary?

- What are our needs? Who is going to defend them? How should they be defended? How important is it to have a strong lobby comprised of artists?

Who is responsible for democracy in a democracy? To some extent, we ourselves are at fault for the non-issue that the arts have become. This election has shown us what has been true for a while: that spectacles don’t happen on wooden stages anymore, that stories are no longer told merely in books and on TV. Many stages have emerged throughout this election, all of which we must begin to inhabit. Doing so will imply hard work, interdisciplinary collaborations, the discovery of new art forms, and ultimately re-definitions of art as a whole. If we continue to ignore the way of the world and the political dismantling of our profession, the bloodletting of Canadian artists is going to leave only empty shells of us behind.

The Opportunity for Arts and Culture under a Trudeau Government

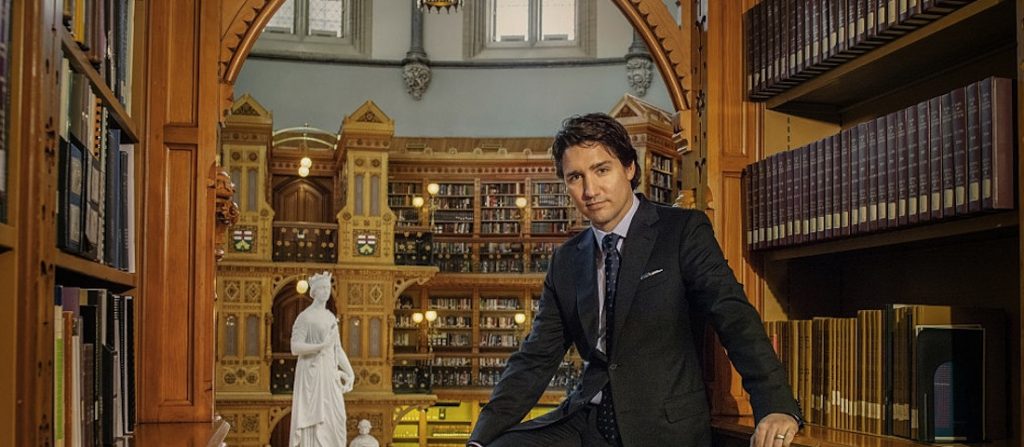

Over the course of writing this article in the ten days leading up to the election, there has been a growing consensus amongst polls and pundits that it will result in a Liberal Party victory. If, as seems likely, Justin Trudeau is set to become the 23rd Prime Minister of Canada, there is a big piece of news to be considered by the arts community across Canada:

We immediately encounter the possibility of a transformed Canada Council for the Arts that has doubled in funding. The Council has already committed to the transformation part, breaking into six sections. Most people invested in this change await a major fall announcement with baited breath to find out what that means practically for artists and arts organizations.

During the campaign, Justin Trudeau announced with fanfare in September that he would DOUBLE the Canada Council as part his campaign platform. If they keep this promise we could be looking at a much larger, completely redefined national arts funding organization in the matter of a few years. On a macro-level, in terms of reinvigorating and redefining Canadian culture, it is a once in a generation opportunity.

This of course will guarantee nothing.

Campaign promises often do not become legislation and supporters of a doubled Canada Council across the country will have to put real pressure on all MPs to understand it is an important issue over which their constituents are engaged on. Thus far, advocacy around preserving the Canada Council for the Arts under a Harper Government has been spearheaded by the Canadian Arts Coalition. Following the election, they could continue to play a new, and one would assume a more gratifying, role coordinating not just the protection of the Canada Council, but its expansion under a new Government.

If, however, all of these efforts are successful, it could still be very easily scuttled in terms of having a tangible impact for both artists and Canadians who want the systems behind our cultural production to evolve.

Major organizations keep an A-List Board of Directors for exactly this type of moment in the zeitgeist. One needs only look at how Luminato was formed through a couple of businessmen having the right Liberal Party connections to understand how power and influence could trump informed analysis of arts funding at the political level. The minute this money becomes real, emails will be sent, coffee dates will be made, phone calls will be scheduled, and cocktails will be had. The goal will be to ensure this doubled funding re-enforces cultural power structures already in place.

This is especially true at this moment because the powers-that-be are nervous about the Canada Council changes. The feeling on the ground is that the transformation, which is going ahead regardless of new monies, would likely result in cuts for large institutions so room can be made to support new organizations and new practices. Any new funds made available will be targeted by these organizations to insulate them from having to adapt or collaborate in new ways. The old system – only bigger.

This sort of lobbying won’t come from the tens of thousands of individual artists working away in studios, rented rehearsals halls, attics, and make-shift recording studios who have likely created a production model that runs off of their laptops, many of whom are not earning a living wage. Yet, this moment is an opportunity for the rapidly expanding pool of independent artists that are under-represented in our cultural policy.

We excel at both innovation and efficiency out of necessity. We are where new movements and new ideas are generated as the laboratories and R&D facilities for Canadian culture. This system often operates on the backs of unpaid artist labour through how it supports and informs institutional work. Independent artists are the future of the arts in Canada, and we have been living in poverty and obscurity.

If we are about to engage in a major transformation of how our government invests and participates in arts and culture, let’s make sure we’re not entrenching more of the same old structures by ending the idea of “Majors” who get their funding no matter whet while less-connected art compete against each other. We need to create structures that invite new energy and artists to be culturally empowered. Our entire notion of what culture is -from something that broadcast by elites, to something interactive that we all can participate in, is changing.

Call or email your (all of a sudden likely Liberal MP) and let them know you support the campaign promise Prime Minister Trudeau ran on to double the Canada Council. Also let them know that you want this to be a transformative moment in how it operates. That art and artists are best served by directly receiving these funds. I also suggest liberal use of the hashtag #2xCC4ART.

Let’s create a mode of cultural production that is, in short, artist not institutionally driven. First things first though, the money has to turn from a campaign promise into a budget reality, and that will require everyone working together.

#CdnCult Times; Volume 6, Edition 1: THE ELECTION

It seems significant that we launch this 6th Volume of SpiderWebShow on the first day of the post-Harper era. Our long, long election is over and Canadians have turned their back on many of the policies and ideas that defined our Federal Government for the past decade.

This Edition was curated by asking two other theatre artists to join me in responding to the election itself, before knowing what the results were. Fannina Waubert de Puiseau has written on the contradictions and complacencies that are inherent in being an artist caught up in this electoral system, Kevin Loring provides historical context and some hard truths about how the election relates to divisive and racist politics from 100 years ago, and I have written on the implications of a Liberal victory for arts and culture policy.

A new era is upon us. Power has been passed between competing parties and interests peacefully and no major incidents of fraud or violence have been reported. As we continue to have a government modelled on the British Parliamentary system, it is probably best to quote Winston Churchill on what these articles reinforce for me cumulatively:

‘Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others.’

#MelinaLaboucan-Massimo #MildredFlett #BonnieMJoseph

Andy Moro and I started working on In Spirit in 2007. The impetus sparked after seeing Andy’s work in dada kamera’s fond farewell at Buddies in Bad Times Theatre in TO. I had long been musing on a work about a girl who’d been abducted and murdered. I felt it was all I could do to contribute to a solution to these recurring tragedies. Once I saw Moro’s work, I felt the play I could conceive of was possible.

Child safety visits from police officers were not uncommon to schools in 1980s in Lethbridge Alberta. We learned about child abduction when the trend of wearing one’s name emblazoned in tidy black velveteen letters on the back of a t-shirt hit its peak. There had been cases where strangers approached a lone child and called them by name, which struck the fear of Satan into my little half-breed catholic heart. How could one evade an abductor without being rude to a real acquaintance of her parent? “Tara? I’m your mom’s friend from work. She asked me to come pick you up.”

We spent summers where my maternal roots are, the lower Nicola Valley in B.C. There I learned I already knew people who had first hand experience with having a child plucked from the universe. This place I regarded as idyllic and friendliest toward children – a cluster of Indian Reserves in the interior – was the crime scape for that greatest of horrors. I felt the world shift beneath my feet, and an obsession planted.

Years later, as a practicing theatre artist in Toronto, I reconnected with friends and family directly affected by the inexplicable loss of a child. Some had been living with loss for several years, and some had had it scorch them more recently. I had reached certitude around my own decision not to have children, and ended a marriage. I was keenly aware this kind of crossroads was one that some parents only ever wished for, for their children. Surviving heartbreak was a privilege, for it meant I was alive. After several long conversations with a number of people, (whose identities I will keep close out of respect for their right to move forth in life, rather than in grief) I received what permissions were possible to attempt a fictionalized account of one girl’s experience at the end of a foreshortened life.

While writing, I was roomies with one of my favorite actors and regular muse, Michaela Washburn. It was she who brought me to see Moro’s work. There was a confluence of inspiration that night, and shortly thereafter I penned a first draft, with the knowledge of Washburn’s considerable gifts allowing the voice of the character to come through to the page. Within days, Moro, Washburn and I were in studio, working the script. We worked like a team of sculptors, shaping the piece together, plying our individual strengths and insights. Our first invited audience came to see our work-in-progress a few days later.

The response that day, in 2007, was extremely mixed, with the most alarming remarks at the time even more surprising today. The tiny inaugural audience consisted of Indigenous theatre students, arts worker colleagues and former schoolmates of mine from Red Deer College. The room felt safe. All present spoke relatively frankly considering how often I see the death of an early play by politeness. Three of a dozen people genuinely had the curiosity about who would care to hear the story of an Indigenous girl gone missing. These people were being honest, not cruel, and yes, they were all Caucasian. It was an important thing to hear, though the expression of it silenced the young Indigenous woman present whose best friend had gone missing while they were still in junior high.

The awareness around what is now a hashtag – #MMIWG – has increased exponentially in the general population. Every major party in Canada has stated its stance on the issue – an issue that is never just an “issue” for the families who have lost their beloved. Mulcair has promised an inquiry within 100 days of an NDP victory, while Harper maintains his belief in the futility of such a thing. Adding to the offense is the messaging the RCMP, on Harper’s watch, has resolved to propagate in the media.

“70 per cent of murdered aboriginal women killed by indigenous men: RCMP” declared a Globe and Mail headline of April 2015. Similar headlines blazed up on the CBC and in the National Post. More than demonstrating the danger in the reductive nature of statistics, it revealed the bare-naked values of a country that has systemically tried to eliminate Indigenous people since its inception.

While Stats Can doesn’t collect data about homicides by race, our nearest neighbors do. According to a 2012 report cited in The Economist, in America “less than 20% of murder victims are killed by someone of another race.” One can deduce that more than 80% of murder victims are killed by someone of the same race. Why does Canada not collect crime stats based on race? The old “we’re too polite” notion obviously doesn’t fly among most Indigenous people. Had we access to similar information, the headline might read “Aboriginal people 20% less likely to be killed by their own as compared to the general population.”

The commonly cited number of #MMIWG today bobs around 1,200 after a 2012 RCMP report more than doubled the long-held 500. This number accounts only for women and girls missing and/or murdered since 1980.

The conversation around missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls has changed a lot since In Spirit began its journey in 2007. At the time, few plays offered a human telling of these stories, though they were profoundly influential. Marie Clements’ Unnatural and Accidental Women had blown the walls off my artist brain when Native Earth staged it at Buddies in 2004. Following this, I read and then saw Yvette Nolan’s Annie Mae’s Movement. In recent years we have ever more works on the subject from Keith Barker (play The Hours That Remain), Sarain Carson-Fox (dance The Missing), IsKwé (song Nobody Knows) and the artists’ collective that headed the exhibit Walking With our Sisters, to name a few. This lends hope while doing its part to point to the ubiquity of the problem.

Last year, through Native Earth, In Spirit played at Full Circle’s Talking Stick Festival in Vancouver where, by the grace of Creator, a group of twenty people (who identified themselves) with direct connection to the missing and murdered attended a performance. Our team was embraced by these mighty people, and blessed in our work. Since this time, ARTICLE 11 has enjoyed full creative control of the work, and – finally fully housed in an Indigenous values system – the piece is more powerful than ever.

_________________________________

In Spirit plays August 5 & 6, 8pm at Harbourfront Studio Theatre and August 8 at 10pm, under the Gardiner in the Fort York south parking lot. All shows are free and followed by an audience/artist conversation.

About the Author: Tara Beagan is Ntlaka’pamux and Irish “Canadian.” She humbly asks that you take five minutes to look up the missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls and learn the story of one person. Learn her name and speak it. We change the system that kills when we know each other’s stories.

Where Art Meets Fuck You

On Monday evening July 27th, hundreds of protestors for #BlackLivesMatter marched onto the Allen Expressway, one of the busiest highways in Toronto, and blocked rush-hour traffic for 2 hours.

Also on Monday evening July 27th, at the exact same time, a group of theatre artists gathered at the Storefront Theatre for the latest iteration of the political cabaret Wrecking Ball.

Which event did you hear about first?

Established in 2004 by Ross Manson and Jason Sherman, Wrecking Ball is a responsive evening of theatre, created in line with current headlines and rehearsed and presented within a short time frame. Although, the volunteer organization has gone through several teams of leadership, its mandate and style have remained the same. Theatre that is ripped from the headlines, to the page, and to the stage, in a guerrilla rough and ready way.

This particular evening of Wrecking Ball was curated around the theme (and hashtag) #DeadCoonTO. It was referencing the popularity of the tag #deadraccoonTO which went viral on July 9. This meme followed the discovery and subsequent ad-hoc memorial of a dead raccoon found on a busy Toronto street corner. Whether viewed as satirical or in earnest, people did respond to the sight of the raccoon, re-tweeting photos thousands of times, and even contributing to the memorial in person. The dead raccoon meme was highly criticized in light of the lack of internet response to the shooting of Andrew Loku by police, only a few days earlier on July 5.

Ironically, with the #BlackLivesMatter protest on the same evening as Wrecking Ball, #DeadCoonTO was looking to emulate the very thing it was criticizing. Gathered in the over-capacity Storefront, was our complicity in political performance merely mimicking a significant and useful response to injustice? As a community, does our ability to talk about and concern for real political issues only extend to the stage?

One of the newer elements of Wrecking Ball, is an open-mike feature called Time Bomb. Audiences are given one minute in which to rant about anything they want. Ringers are engaged by the organizers to bring some quality rants to the stage, but otherwise, it is open to any audience member who may speak on any subject. When their time is up, a joyful ‘bomb’ is projected and met with cheers. BOOM! It’s ragged but fun and democratic.

To create an atmosphere of encouragement for the Time Bombs, the organizers do a little call and response with the audience. It begins with the call, “Fuck you!” to which the audience responds with “Fuck YOU!”. And then it repeats, and so on until the audience is significantly riled up. Admittedly, I have been trying to watch my own swearing, so permission to do so in a different context is very freeing.

According to my seatmate, my calls of ‘Fuck you’ bordered on gleeful.

Fuck you!

Fuck YOU!

FUCK you!

FUCK YOU!

BOOM!

Intermission. People buy more drinks, schmooze, step out for a cigarette.

Near the stage, I crouch on the floor with writer and spoken word artist Donna-Michelle St. Bernard. First, we laugh and joke before our tone turns serious. We have cried together and in opposition at times, so it’s easy to get to the truth quickly in our conversations. She performs later – the closing act in fact. She’s worried because the evening has at times been satirical and funny. She didn’t want to bring the room down with her piece, which she calls ‘angry’. We look each other in the eyes. We agree. If we aren’t fucking angry, why are we here?

I sit and wait for the next half of the performance and think about anger. What is beyond angry? Is it art? It’s so pretentious a conceit, I almost throw up the vegan gluten-free donut I just ate. I check twitter.

We’re back. Another Time Bomb.

Fuck you!

Fuck YOU!

BOOM!

Fuck you, we say in order to create a safe space.

Do you feel safe when you read ‘fuck you’?

I respect the people on stage, the organizers who volunteer their time, the artists putting forth their raw work, the audience who have made a choice to come.

Fuck you.

Fuck

You

f…..u……c……k

y….o…u…

I stop saying it.

I’m a writer. Words mean something.

It occurred to me much later, that I was reminded of an acting exercise from theatre school. Repeat until you really meant what you were saying. Repeat until you believe the words. Repeat until your scene partner believes you. Repeat until it is true.

Fuck you.

There is an inherent violence in the words. Does knowing we are saying it in order to create a safe space change the power of the words? As the evening continued, the number of people willing to rant dwindled. Did they feel safe? Or were they filled with other emotions? Despair. Helplessness. Futility. Inadequacy.

I check twitter. The #BlackLivesMatter blockade on Allen Road had ended. Our evening was coming to a close too, ending with Donna-Michelle. She was not wrong. She brought her anger. The lights fade. The evening is over. Everyone cheers.

I am uncharacteristically quiet. I want to be myself. I escape quickly.

What is the point of doing these quickly thrown together works? What actual good is placing our political questions onto a stage? What is the actual point when there are people who directly and actively work to address injustice? Maybe Wrecking Ball is not for anyone else but our community. Maybe it is simply our time, our space to say fuck you. Maybe, like a pressure valve, we have to say it. Maybe, we need this space for our rage, and not just us in theatre, but society too. Rage is chaotic and often destructive. But I would also argue that this makes it inherently creative at its core.

Wrecking Ball to me, is not a fuse, but a pilot light. Lit just a little. Just enough. Just enough to keep everything going. Just enough to remind and connect us with the rage within. Just enough light to keep going.

Because, because…

We all know what happens when there is too much and it become unmanageable – too much rage, too much fuel –

BOOM.

#CdnCult Times; Volume 5, Edition 8: WHITE PRIVILEGE

It is a complex exercise to curate the White Privilege Edition of something as a straight white male who comes from a lot of privilege. An issue that has come up repeatedly in discussions around ethnic diversity in Canadian theatre is that although diverse works are occasionally programmed, the person who chooses what and who is programmed is still usually a fairly privileged white guy. As is the case, again, with this edition of #cdncult.

I have sought to mitigate this tradition by working writers who had already been identified as leaders by their communities. Each of these writers has been or is Artistic Director of a significant theatre company. We have also commissioned these authors with the freedom to write on whatever topic or issue best addressed contemporary concerns about white privilege.

So hopefully this edition is an offer of a platform and solidarity as opposed to a curated perspective. Tweet at #cdncult if you have more thoughts on this.

During the recent Municipal election Toronto’s eventual mayor went on record saying he didn’t think white privilege exists. Reading from Tara Beagan’s piece on creating work about Missing and Murdered Women, Camyar Chai on the bias every ethnicity faces, and Marjorie Chan’s article on the #DeadcoonTO Wrecking Ball, it’s hard not to feel the Mayor has some on-the-job reconsidering to do.

If nothing else, this edition of #cdncult definitely exists.

Brendan Healy

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Criminal Genius

Play: Criminal Genius || Playwright: George F. Walker

Shoot: NDG || Model: AJ Korkidakis

STEVIE: I gotta keep lookin’. It makes me nervous when I’m not lookin’.

ROLLY: Get away from the window.

STEVIE: I can’t.

ROLLY: But I’m so nervous I can’t think. I’m trying to think but I can’t.

STEVIE: What are you thinking about?

ROLLY: A lot of things.

STEVIE: Like what?

ROLLY: Like why won’t you get away from the window when I ask you.

STEVIE: Because I can’t.