An Awkward Call to Arms

As the leader of the Indigenous Performing Arts Alliance (IPAA), a national arts service organization that claims space for all Indigenous performing artists, I am proud to collaborate with Michele Decottignes of the Deaf, Disability & Mad Arts Alliance of Canada and Donna-Michelle St. Bernard of the ADHOC Assembly in an advisory role to the Professional Association of Canadian Theatres (PACT) on the recently announced All In: A National Equity, Diversity & Inclusion Initiative. Our organizations presented this initiative, alongside PACT Executive Director Sara Meurling, to the artistic leaders at the PACT Conference on Treaty 7 Territory [Calgary, AB] in May 2016. The presentation instigated a discussion about historical inequities for Indigenous and culturally diverse artists within the theatre sector. Inspired to make change, PACT members committed to taking action in their forthcoming proposals to New Chapter funding from the Canada Council for the Arts. In order to galvanize this verbal support into action we created this Awkward Call to Arms / Appel aux armes.

It is no secret that the arts funders on these lands and waterways are making Equity Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) projects a funding priority. At the 2016 Prismatic Arts Festival in Halifax during the Opening Gala Keynote Address Simon Brault Director and CEO of the Canada Council for the Arts spoke plainly about the Council’s responsibility, particularly in the context of a doubled budget, “We want to take a more horizontal approach where equity is made a reality – and diversity becomes a non-negotiable priority that we are all accountable for. Not just for one section of the Council. But across all our programs and activities.”

At IPAA’s recent Intertribal Gathering in Dakwäkäda [Haines Junction, Yukon], traditional and self-governed territories of the Champagne and Aishihik First Nations, Kerry Swanson (Cree-Ojibway) from the Ontario Arts Council reported that all jurors will be provided with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples to consult when issues of cultural appropriation arise during deliberation. Supporting our artistic peers on the selection committee is key and it is vital that we find common ground around issues of access, privilege, sovereignty, and white supremacy (to name a few) in the pursuit of equity. The Awkward Call To Arms is an opportunity for our sector to develop a shared approach to New Chapter projects in the crafting of the grants before they reach the jury.

I had the privilege of attending the Theatre Communications Group conference in Washington, DC this June, thanks to the generosity of the Playwrights Guild of Canada. At this national event there was a groundswell of Indigenous and culturally diverse theatre artists gathering in affinity groups as well as featured throughout the conference. Anna Deavere Smith opened with a plenary session, including characters from her groundbreaking solo shows exploring race relations through performance. Within her presentation she referenced accomplishments by the late August Wilson and the dearth of African American Theatre companies active today. Staggering statistics about white supremacy within the performing arts combined with her powerful performance made an impact on the assembled audience. She closed stating, “those of you who feel moved, must move.”

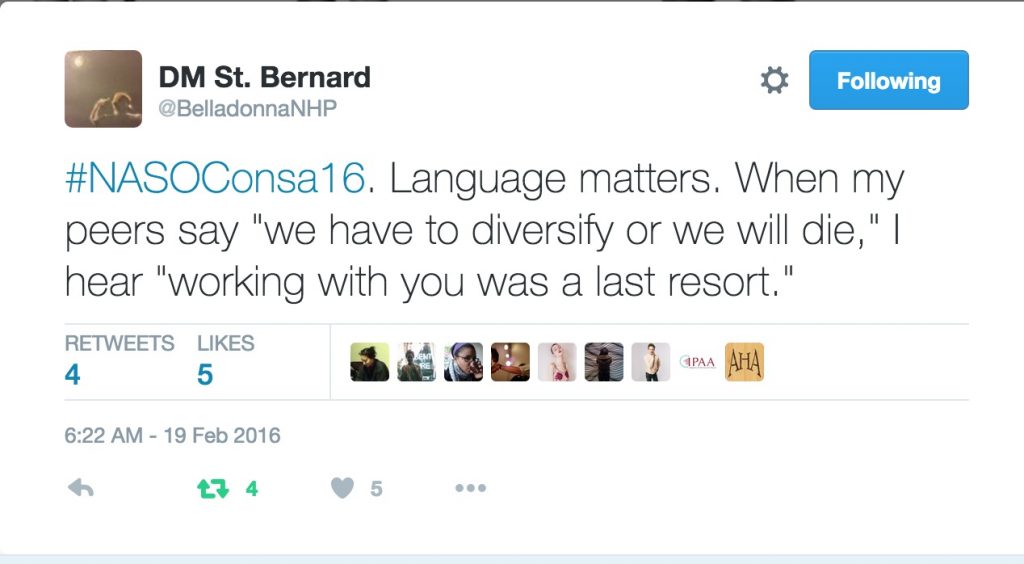

Perhaps it is my habit to overthink, but following this clear and impassioned directive I felt my heart sink as the audience erupted with cheers and applause – is she asking this room of artistic leaders to vacate their leadership positions to make room for Indigenous and culturally diverse leaders? And further to that, are we all clapping in agreement? Turns out my interpretation of the word move – requiring a radical power shift via succession – was not the pervasive understanding in the room. Rather I suspect her words were taken as an impassioned call for the assembled gatekeepers to make change within their existing structures, status quo preserved. I bring this up in the context of Allies to highlight how perspective and self-interest has a direct impact on social justice in the arts. In the age of Truth and [re]Conciliation, directives for EDI are not all interpreted in the same way and this creates a potential for art-making endeavours that are eligible for prioritized funding without challenging the oppressive structures responsible for inequities within our sector.

I invite you to read the open letter from John Kim Bell (Mohawk) called Understanding Reconciliation in the recent issue of alt.theatre – Cultural Diversity and the Stage. Bell has been called “The First North American Indian Conductor” and in this letter he speaks of the ballet he produced, co-composed and directed In The Land Of Spirits. The systemic barriers he overcame creating this production with an all-Indigenous creative team in 1988, before touring it nationally in 1992, are juxtaposed by the 2014/15 Truth and Reconciliation (TRC) sponsored commission and national tour of the Royal Winnipeg Ballet’s Going Home Star – Truth and Reconciliation that, to my knowledge, has not one Indigenous dancer on stage. In his open letter John Kim Bell states clearly how funding for [re]Conciliation from the federal government, “should go to building capacity within the Indigenous community directly.” Furthermore, he shares, “In my long career, I have learned that, unless extra money can be secured, mainstream cultural institutions will give little support for Aboriginal people and projects.”

Enter the $33.4 million of Canada Council New Chapter funding and our Awkward Call To Arms. The first deadline has come and gone and the second deadline is fast approaching (October 31st, 2016). IPAA receives one request a day from potential Allies looking to collaborate with an Indigenous organization or artist on a Truth & [re]Conciliation project. Regrettably, we are unable to adequately (and patiently) respond to every request given the short turnaround and the existing collaborations and commitments IPAA has underway. The timing of these inquiries is a symptom of artistic leaders seeking partnerships to secure funding – in my experience, meaningful collaborations are motivated by artistic compatibility with the needs of community at the centre rather than additional revenue sources.

IPAA has honed our Ally Membership criteria in response to this fervoured interest in Indigenous collaboration. Allies are now asked to tell the story of their previous engagement with Indigenous artists so our members can hear (in their words) how they self-identify as Ally. Stand out profiles include clearly articulated IPAA Member points of access from Made In BC: Dance On Tour and a reflection on the Ally’s responsibility to consider what they receive when collaborating with Indigenous artists (and what they are willing to offer in return) from Individual Ally Member Kristina Lemieux.

Each of us has parts of our communities we could be better advocates for through the development of meaningful collaboration. IPAA’s mandate of claiming space for all Indigenous performing artists implicitly includes artists with diverse abilities. Working with Michele Decottignes at The Deaf, Disability and Mad Arts Alliance of Canada on the All In Initiative reminds me how much work I need to do to become a better ally to the Deaf, Disabled and Mad artists within the Indigenous performance communities (and our organization’s mandate).

View for yourself the Ally Organization and Ally Individual application(s) and consider becoming a member of IPAA as a step in the process of creating relationships with Indigenous performing artists, organizations and communities.

Meaningful cross-cultural collaboration is the long game and it needs to start right now.

Lois Dawson is a Vancouver-based stage & production manager. Her stage management credits have ranged from original musicals to site-specific spectacle, from Swiss opera to the Fringe festival, and from one-person political comedy to the Olympics. She is the president of the Jessie Richardson Theatre Awards, sits on the national stage management committee for CAEA, and is a graduate of Trinity Western University. She can be found online at

Lois Dawson is a Vancouver-based stage & production manager. Her stage management credits have ranged from original musicals to site-specific spectacle, from Swiss opera to the Fringe festival, and from one-person political comedy to the Olympics. She is the president of the Jessie Richardson Theatre Awards, sits on the national stage management committee for CAEA, and is a graduate of Trinity Western University. She can be found online at