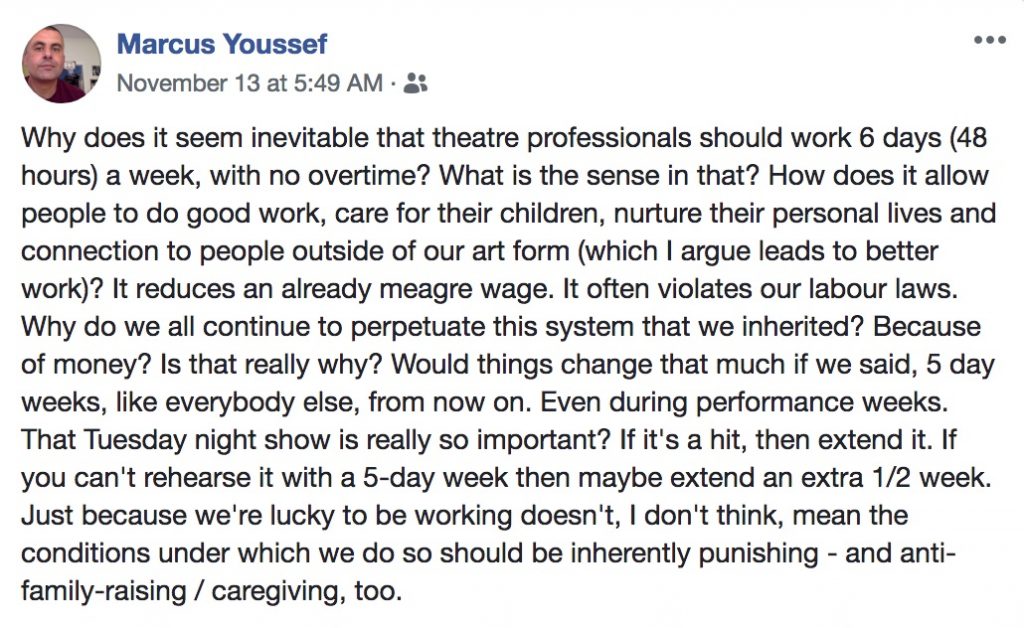

In a Facebook post on November 13, my friend and recent Siminovitch Prize winner Marcus Youssef asks,

Why does it seem inevitable that theatre professionals should work six days (48 hours) a week with no overtime? How does it allow people to do good work, care for their children, nurture their personal lives and connections to people outside of our art form (which I argue leads to better work)?

This culture of overwork is reinforced by collective agreements that stretch the limits of labour law with 6-day weeks and days that allow working ten hours out of twelve in one 24-hour period. These are the professional standards for onstage workers, and the expectations for offstage workers like stage management are equally if not more burdensome.

Stage management are considered employees and are therefore somewhat protected by labour law, but let’s think realistically about the logistics of some members of a team working within labour standards and coordinating contract workers who are not protected by those same laws?

Let’s break it down.

The average work day during rehearsal for an actor who is a member of Canadian Actors Equity is eight hours. This does not include any time required to execute physical, vocal, emotional or mental warm-ups to prevent injury and promote excellent work. Lunch (60 minutes) and breaks (five minutes for each one hour, totalling 20 minutes) are paid, but generally contractors stay onsite.

Stage management and directors work the same hours, and in addition, arrive early to prepare or have meetings with other artists.

Let me ask you: how effectively is your time used in the rehearsal room between 3:30-6:00pm?

None of this time takes into account preparation. The hours of memorizing and running lines at home. Researching a role. Working on physical and vocal choices. Considering motivation, objectives, and strategies for each fucking word you utter.

So with six hours and 40 minutes of active work-time in the room and paid breaks, I suppose we are better off than, say, fast food employees. When I worked 8 hour shifts at A&W my wage was calculated hourly and my lunch hour and breaks were unpaid.

There are obvious differences between working at A&W and rehearsing and performing a play. One involves integrating intelligence, imagination, physical agility, memory and heart. The other… does not. Nor does it require hours of preparation.

This is not to argue that working at A&W is an easy job or does not merit a living wage.

Rather this is an argument for the people who design, agree-upon, implement, and enforce the labour standards applied to live theatre to consider the very real impacts of exhaustion, chronic stress, and long-term anxiety on the workers (AKA: artists), never mind the product of their labour (AKA: the art).

The work suffers.

The. Work. Suffers.

I write this as a freelancer, the mother and primary caregiver for two kids, who right now is so fucking tired that I can barely string these words together.

Do not ask me to make art right now. I can’t. I’ve tried. My imagination doesn’t fire in this state without very specific measures in place: childcare, five hour day, mental health breaks, and generous collaborators. All of my intelligence, instinct, and imagination is wrapped up in solving the problem of making it through the day without yelling (much) and figuring out the menu for three meals and two snacks.

The conditions I describe above shouldn’t be considered special requests. They should be the baseline.

Parents and caregivers aren’t the only people affected by these work conditions—though let’s all take a moment to send some love to the solo parents. Consider the artists whose bodies and minds need more rest than is allowed by our training and work systems that mistake endurance for rigour.

Recent work to improve accessibility and inclusion practices in theatre have to led to (many) great things, including adopting the practice of identifying what each participant needs to do their best work in the room at the beginning of a process—and then filling those needs. Most people think this applies to artists and workers who need time and space to cope with medication schedules, physical or mental limitations. BUT ISN’T THAT ALL OF US? We all have limitations. We all need rest and space to be our best selves in the room.

There is a whiff of classism in all of this, too. The way the work conditions are organized right now privileges workers who can afford to be broke, folks who have family (chosen or otherwise) who can support this economically irrational choice. This in turn makes participation in this fucked up system impossible for people for whom artistic expression is less integral than day-to-day subsistence and the long-term sustainability of themselves and the folks they are responsible for and to. These artists represent a broad range of intersecting demographics that include age, ability, socio-economic background, race, mother-tongue, among others. The work conditions we accept and promote in the arts actively inhibit these people from participating, which in turn impacts whose voice is heard, in addition to the very quality of the work created.

There are other industries with comparable work conditions: any entrepreneur starting a new business can attest to long days and low pay. These workers are in control of their work environments, and can make choices to prioritize other aspects of their lives.

In our industry, where mental, emotional, and literal acrobatics are required for performance and rehearsal, we’ve bought into the idea that we, like any other factory line worker, can work for eight hours in a row, six days a week. We have signed agreements that endorse these work conditions as though they promote creativity and art-making.

So what can we do?

We can add these very real concerns to the table during labour negotiations.

We can advocate for childcare on site where we work, and childcare stipends when that’s not possible.

We can advocate for shorter work days when negotiating contracts.

We can advocate for ever-increasing flexibility and freedom to self-determine rehearsal schedules based on the needs of the artists engaged in the projects.

When we sit as members of assessment committees, we can actively support artists and producers who include childcare, shorter rehearsal days and weeks in the budgets for our project proposals when applying to arts funders.

We don’t need to be this tired all the time. We don’t need to sacrifice our family and personal lives. We can lead fulfilling lives outside of our work. We can create work conditions that promote the inclusion of artists from a broad range of intersecting communities.

But we need to do it together.