As questions concerning the origin(s) of funding become more and more politicized—i.e. #divest—do we not need to start reflecting deeper on where the money we use to make so much of our theatre and performance in Canada comes from?

I’ve just finished an MFA degree in Vancouver. Now graduated, my peers and I are starting to pursue public funding through municipal, provincial, and federal arts councils to support our work. Like in most MFA programs, we spent a great deal of time discussing the ways we conceptualize the public (as an agent, as a site, as a multiplicity, etc.), but we did not once discuss within the context of our art education the relationship our art could have with the public via the interface of taxation.

So let’s talk about public funding and its relationship to artists.

Public funding in Canada is the funding collected through the taxation of the Canadian people by Canadian governmental bodies. People are taxed for their incomes, their property, and the use of their wealth. Once collected, the funding is redistributed to a variety of services, including arts agencies—municipal, provincial, federal. These agencies then redistribute the funding to artists. Thanks to our government and the public’s taxation, public funding is, and will continue to be, the means of most of our productions.

Even though our Prime Minister has increased Canadian arts funding (the most recent budgets stating commitments of $1.9 billion in 2016 and $1.8 billion in 2017), the relationship artists have to the public through public funding, remains the same.

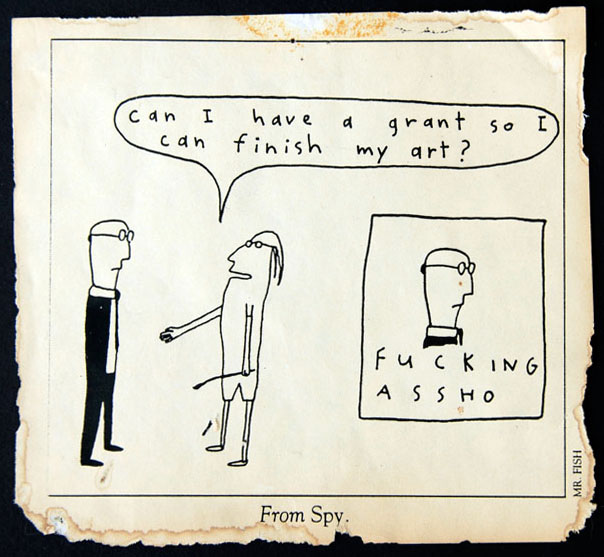

Our public funding seems ‘neutral’ in that we do not need to moralize our art practices in relation to the public when we receive it. Our public funding begs no special debts or treatment in the process of our art making. Public funding for artists does not restrict the usage of the funding for a specific public good; rather, public funding for artists assumes the art will, by virtue of strengthening cultural practices, benefit the public. So once a grant has been granted, the funding arrives as a cheque in the mail no different than any other work payment. Art, like much else, can happen without answering to the origins of its capital.

I am not saying this ‘neutrality’ is a bad thing. It helps many of us work and think outside of boxes and expectations. Nobody wants a top-down system in which we’re told to make certain kinds of art by a government (#socialistrealism).

But, with respect to the public, the ‘neutral’ mask given to the public through taxation makes the great patron of our country’s artists a highly abstracted body. In the niche of contemporary Canadian art, sometimes it feels like the public is everyone and sometimes it feels like the public is only those who care about the art—only those who buy tickets (on top of their tax deductions).

This is really important. Despite ostensibly coming from the taxes of the public as a whole, our art (like a federal highway in another province or a teacher in another city) is not something every member of the public takes advantage of—nor should be forced to. Inherent to our debts to the public is a certain exclusiveness—by region as much as personal interests. There is no the public.

So given both the ‘neutrality’ of our relationship with the public and the practical restrictions of collapsing Canadians into singular public identities (all Canadians, all Vancouverites, all Nova Scotians), can we really say that receiving public funding equals having public support?

I don’t think so.

I also don’t think an artist’s desire for public funding from government granting agencies is quite so easily reduced to “we want public funding to make our artworks because we believe (some) people will be impacted positively by them” or “we want public funding (with its neutrality) to make our artworks” or “we want public funding (because we don’t want to work joe jobs).”

These desires for public funding likely form a spectrum that we slide along more than fixed positions. Linking these positions is the fact that any desire for public funding collected through taxes is a desire for government patronage as opposed to a public patronage that does not involve the government, such as support directly from fandom, box office, and/or fundraiser-based funds.

Government patronage can, through the concept of democratic representation, still be ultimately attributed to a people who chose someone who chose someone who chose someone to make a decision for them. But as we know, governments are not their people, and so a qualitative difference remains between an artist with government patronage and one with public patronage that does not involve the government. A distinction is especially palpable between both of these categories and an artist with no patronage at all.

So if getting funding from the government doesn’t really give an artist a direct relationship to ‘the public’ who produces that funding, what does the artist get with their public funding?

One thing they get is status. The patronage of an arts council, their brand and name, forms a significant class status marker within the Canadian artmaking community. That marker means little to people outside of our own art communities and little more to public audiences attending our works. It is also not a marker many artists seem to respect at the level of how it is acquired—we all ‘adjust’ our words and numbers on grants, don’t we?—The status we receive however, along with the funding, is nevertheless something we artists can use, and do use, to construct classes within our community.

Public funding explicitly marks who has government patronage and who does not. It also marks whose patronage and status can beget more patronage and more status in the future.

On the one hand, you could argue that because so many of our experiences in Canada are funded by the public’s taxes, interrogating our relationship with public funding seems a bit disingenuous. And it is. We are very lucky in this country to be able to simply apply for money and make terrible—or great—art if we get it.

At the same time, however, we are artists, and I think that such an identity presumes that we should not do things, such as relate to money, the same way others do. This could be a gross moralizing of the artist, but I have a hunch most of us already do perceive money differently from venture capitalists (who don’t invest in our trade), and most of us tend to carry a certain ‘refuse-to-question-the-value-of-public-funding’ attitude.

There’s just more “value” to public funding than can be measured in CAD.