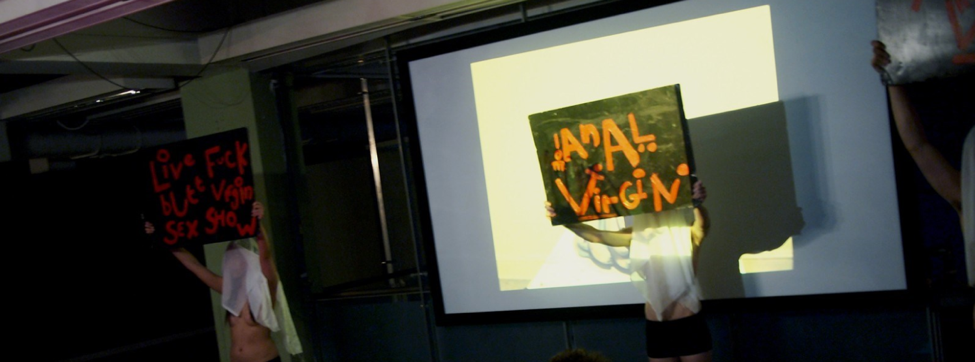

In October of 2014, 19-year-old gay student Clayton Pettet, a virgin, announced he would perform live sex with a man as part of a performance interrogating the heteronormative and societally constructed concept of virginity. The piece, “Art School Stole My Virginity,” sold out, sparking a viral media firestorm that raged somewhere between an erupting volcano and a collapsing sun. But when the spectators arrived, the performance was not what they anticipated.

As Pettet explains, and as tweets about the event show, the vast majority of the audience had come to witness a queer body being penetrated rather than a work of performance art. The queer body in performance is often a site of fascination for heterosexual folks. This fetishism stems from a view of queer bodies and queer sex as “other” and is felt twofold by queer bodies that are also racialized. Pettet’s intentional decision to replace the act of penetration with acts such as scrubbing the words “ANAL WHORE” off his skin highlighted this voyeuristic interest in the queer body.

As Canadian theatre continues to display a progressive interest in elevating the voices of queer performers, we need to change the way queer bodies are represented onstage. We must avoid positioning the queer body as a site of consumption, particularly when mounting queer stories that highlight sexual (in)experience or changes to the body.

Here are four steps toward creating equitable and non-fetishistic representations of queer bodies and queer stories on the stage.

1. Interrogate the narratives laid out for your queer characters. When making theatre as an ally, look closely at what kinds of stories you are sharing and why.

In 2014, Toronto’s Buddies in Bad Times theatre mounted Outside, a play about a young boy named Daniel who is forced to change schools because of homophobic bullying. Both onstage and in the world in which we live, homophobia often involves intense trauma, but it’s important that Outside doesn’t end in tragedy for Daniel’s character.

The sensationalism of trauma may sell tickets, but it can ultimately harm the community you are representing. Tragedy must be represented, but these narratives have become expected by heterosexual audiences, who may find it easier to understand the oppressed queer body as a site of violence than the idea of a vicarious, vibrant, living queer identity. Watching queer characters live joyfully subverts the cultural norm and shows much more compassion toward queer audiences.

2. Question how you represent queer intimacy. Questions about how someone enjoys intimacy with a partner and what sexual organ they have are completely inappropriate, but queer people frequently face these questions from cisgender and heterosexual individuals, who feel entitled to the answers. Queer sex and naked queer bodies are a site of fascination for non-queer audiences.

Queer intimacy onstage, in film and television, is represented wildly differently from heterosexual intimacy. Queer performers are often either desexualized—which removes their sexual agency and shames queer sexual desire—or oversexualized—which caters to the interested voyeurism of the audience.

In Jim Steinman’s Bat Out of Hell: The Musical, a queer-coded character named Tink takes a bullet for the male object of his affection, Strat, and dies in his arms. Despite Strat’s repeated proclamations that the two of them are soulmates, as Tink dies Strat only kisses him chastely on the forehead.

This kiss on disappointed queer audiences, and skirted an opportunity to present open queer sexuality. However, more overt representation onstage often involves queer actors performing extended intimate scenes.

Representing queer sexuality should not be taboo, but heterosexual directors must compare how heterosexual love is represented in the same story. If your queer couple only makes out while your straight couple is permitted to kiss more tenderly, interrogate why.

3. Normalize diversity among the queer performers you hire. Ongoing misrepresentation of queer characters posits a young, white, thin, attractive, cis, male body as the only queer body. The understanding of queer bodies as “other” is reinforced when heterosexual audiences repeatedly encounter this sensationalized body onstage, rather than a more authentic array of body types, ages, and skin colours.

Fetishization involves a fascination with a particular set of features, coded with cultural ideas that we perpetuate through media and storytelling. To avoid fetishizing individuals, we must understand that these ideas have been developed by one homogenous group. All white, all thin, or all straight casts, for example, are inaccurate reflections of our world, and yet they are rampant in theatre. We must move toward a world that respects all body types and understands there is an amazing array of diverse ways to be queer. In doing so we strive for a future where all bodies are accepted, and sensationalism will no longer occur.

4. A final step toward empowering representation is to listen to queer voices: when we share our own stories, others don’t get to feel entitled to them. As Canadian Theatre moves toward inclusivity, it is not enough to produce queer narratives onstage without considering the consequences of poor representation. It is crucial that we make theatre for queer audiences, and that we make theatre that ethically, compassionately, and productively reproduces the vibrant scope of their lives. In doing so, we create space in the theatre world for undiluted representations of difference, ushering new and vibrant stories onto the stage while empowering queer theatre practitioners of the future.